That was Nestor the young man in the sleeveless T-shirt whose body was like a letter K in the window of the apartment on La Salle Street, one leg bent at the knee on the sill, arm up against the windowframe, smoking a cigarette like a languishing movie star waiting for a call from a studio, and humming a melody line. That was Nestor on the living-room couch, strumming a chord on the guitar, looking up, and writing in a notebook. That was Nestor’s voice heard on the street at night, on La Salle, on Tiemann Place, on 124th Street and Broadway. That was Nestor down on his knees playing with the children, pushing a toy truck into a city of alphabet blocks, the children climbing on his back and riding him like a horse, while in his head there bloomed a thousand images of María: María naked, María in a sun hat, María’s brown nipple filling his mouth, María with a cigarette, María commenting on the beauty of the moon, María dancing long-legged, her body wobbling in perfect rhythm in a chorus of women in feathered turbans, María counting the doves in a plaza, María sucking a pineapple batida through a straw, María writhing, lips damp and face red from kisses, in ecstasy, María growling like a cat, María dabbing her mouth with lipstick, María pulling up a flower…

That was Nestor, eyebrows arched with the scholarly concentration of a physics student, reading science-fiction comic books at the kitchen table. That was Nestor up on the rooftop stretched out on a blanket and sipping whiskey, waking up screaming at night, decked out in a white silk suit, blowing a trumpet on the stage of some dance hall, quietly attending to the drinks, filling a punch bowl during a party in the apartment, dreaming about some of those nights spent with María in Havana, her presence so strong in his memory that around three o’clock in the morning the door to the apartment would open and María would walk like a spirit into the living room and pull off her slip, sliding one knee onto the cot and then the other, lowering herself so that the first thing Nestor felt moving slowly upward over his shinbone and then his knee was María’s vagina. And then she would take hold of his thing and say, “ Hombre! ”

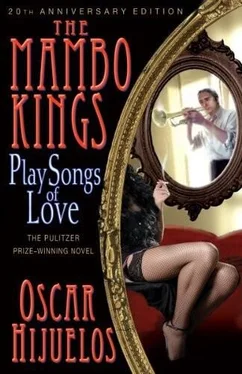

He was the man plagued with memory, the way his brother Cesar Castillo would be twenty-five years later, the man with the delusion that the composition of a song about María would bring her back. He was the man who wrote twenty-two different versions of “Bella María de Mi Alma, ” first as “The Sadness of Love,” then “María of My Life,” before arriving, with the help of his older brother, Cesar, upon the version they would be singing one night in 1955 in the Mambo Nine Club, “Beautiful María of My Soul,” a song of love, that night when they drew the attention and interest of their fellow Cuban Desi Arnaz.

SPENDING LATE NIGHTS OUT, they’d find themselves climbing the stairs to their cousin Pablo’s fourth-floor apartment on La Salle Street at five in the morning. Rooftops burning red, and black birds circling the water towers. Cesar was thirty-one years old then and out to have a good time, preferring to look forward and never back into his past: he’d left a kid, a daughter, behind in Cuba. Sometimes he had pangs for his daughter, sometimes felt bad that things didn’t work out with his former wife, but he remained determined to have a good time, chase women, drink, eat, and make friends. He wasn’t cold-hearted: he had moments of tenderness that surprised him toward the women he went out with, as if he wanted truly to fall in love, and even tender thoughts about his former wife. He had other moments when he didn’t care. Marriage? Never again, he’d tell himself, even though he’d lie through his teeth about wanting to get married to women he was trying to seduce. Marriage? What for?

He heard a lot about “a family and love” from Pablo’s plump little wife. “That’s what makes a man happy, not just playing the mambo,” she’d say.

He had moments when he thought about his wife, a hole of sadness through his heart, but it was nothing that a drink, a woman, a cha-cha-cha wouldn’t fix. He had hooked up with her a long time ago because of Julián García, a well-known bandleader in Oriente Province. He was just a young upstart from Las Piñas then, a singer and trumpet player with a wandering troupe of guajiro musicians who would play in the small-town plazas and dance halls of Camagüey and Oriente Provinces. Sixteen years old, he fled to the dance halls, had a good time meeting and entertaining the people of small towns and bedding down poor country girls where he could find them. He was a handsome and exuberant singer, with an unpolished style and a tendency toward operatic flourishes that would take him off-key.

These musicians never made any money, but one day when they were playing at a dance in a small town called Jiguaní, his youthful exuberance and looks had impressed someone in the crowd who passed his name to Julián García. At the time he was looking for a new crooner and wrote a letter simply addressed “Cesar Castillo, Las Piñas, Oriente.” Cesar was nineteen then, and not yet jaded. He took the invitation to heart and made the journey down to Santiago the week after he’d received it.

He’d always remember the steep hills of Santiago de Cuba, a city reminiscent in its hilliness, he would think years later, of San Francisco, California. Julián lived in an apartment over a dance hall which he owned. The sun radiating against the cobblestone streets and cool doorways from which one could smell the afternoon lunches and hear the comforting sounds of families dining at their tables. Brooms sweeping out a hallway, salamanders skulking along the arabesque tiles. García’s dance hall was a refuge of shady arcades and a long, cool inner hallway. The place was deserted except for García, who sat in the middle of a colonnaded dance floor tinkling at the piano, stout, sweaty, and with a head damp with running hair dye.

“I’m Cesar Castillo, and you told me to come and sing for you one day.”

“Yes, yes.”

For his audition he opened with Ernesto Lecuona’s “María la O. ”

Nervous about performing for Julián García, Cesar sang his heart out in a flamboyant style, using extended high notes and long, slow phrasing, arms flailing dramatically. When he’d finished, Julián nodded encouragingly and kept him there, singing, until ten o’clock that night.

“You come back here tomorrow. The other musicians will be here, okay?”

And in a friendly, paternal manner, his hand on Cesar’s shoulder, Julián led him out of the hall.

Cesar had a few dollars in his pocket. He was planning to wander around the harbor and have some fun, fall asleep on one of the piers by the ocean, as he had so many times before, arms thrown over his face, in fields in the countryside, in the plazas, on church steps. He was so used to looking out for himself that it surprised him to hear García ask, “And do you have a place to sleep tonight?”

“No.” And he shrugged.

“Bueno, you can stay with me upstairs. Huh? I should have told you that in the letter.”

Remaining that night, the future Mambo King basked in Julián’s kindness. High on that hill and overlooking the harbor, that apartment was a pleasant change for him. He had his own room, which opened up to a balcony, and all the food he could eat. That was the order of the household: all of García’s family, his wife and four sons, lived for their evening meals. His sons, who performed with him, were immense, overfed, with cheerful, angelic dispositions. That was because Julián was so loving, an affectionate man who even challenged Cesar’s macho resolve to need or want no one.

He began to sing with Julián’s outfit, a twenty-piece orchestra, in 1937. They had a pleasant “tropical” sound, depending heavily on violins and sonorous flutes, and their rhythm section dragged as in the style of fox-trotters of the twenties, and Julián, who conducted and played the piano, had a penchant for dreamlike orchestrations, clouds of music that seemed to float upward on waves of tremolo-choked piano. The Mambo King would have one photograph of that orchestra — and this sat in that envelope in the Hotel Splendour — of himself in a formal black suit, wearing white gloves, sitting in a row with the others. Behind them, a backdrop of Havana Harbor and El Morro Castle, flanked by pedestals on which Julián had placed small statues of antique themes — a wingèd victory and a bust of Julius Caesar, and large ostrich-plume-filled vases. What was that look on Cesar’s face? With his black hair combed back and parted in the middle, he was pleasantly smiling, in commemoration of that happy time in his life.

Читать дальше