When Mike and I got married, C and L gave us six blushing pink-stemmed wine glasses because, they said, they wanted us always to see through rose colored glasses. (C and L held the bachelorette party in L’s East Village walkup; her roommate, an aspiring comedian, was one of the funniest people we’d ever heard — until she got onstage in front of strangers, and then she froze.)

Over the years Mike and I have had some serious attrition of wine and water glasses, champagne flutes and snifters, steins and liqueur glasses, and carafes and pitchers, as well as plates large and small, cups and saucers, platters, most of the soup bowls, the butter dish in shards. But those six glasses have survived intact.

C is still my closest friend. L stopped acting, went back to school and moved to Brooklyn — not so far away at all — but once there was a half-hour train ride, I saw her less and less. The last time I was with L was New Year’s Day at the end of the 1980s; we talked and laughed and ate and couldn’t have known that we wouldn’t see each other again.

If you think this is a story with a climactic or heartrending ending, it isn’t. We just never got around to making plans. We spoke a few times on the phone. Years later I ran into a mutual acquaintance and asked after L, and we said we should all get together, and we didn’t. We had young kids then and full-time jobs, households, commutes. After awhile, so much time had passed that it would have felt strange to call. Where to begin? Before we knew it, 20 years went by.

I wonder sometimes what we’d have said to each other if we’d understood that it was the last time, just as I wonder how it would have been if I had known that rushed phone call while I was trying to put dinner on the table on a Monday night would be the final time I spoke to my father, or if I had recognized the night — I can’t even remember it — that was the last time I would pick up one of my sleeping sons and carry him to bed.

Sometimes things shatter. More often they just fade.

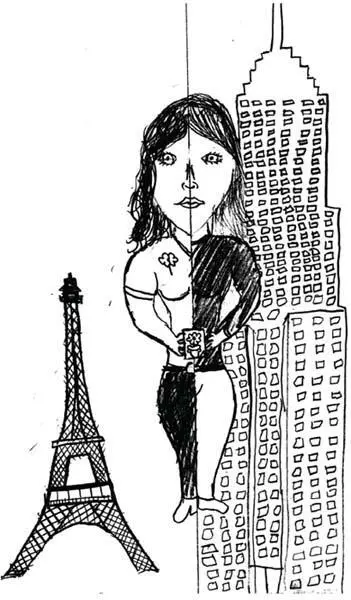

I met A at a colloquium in Paris in 2007. She stood out among the French academics and their American guests both because of her flamboyant manner of dress — many colors, none muted — and her boundless exuberance. Over dinner I learned that while I had been sitting in cafes in Greenwich Village in the 1980s, A was escaping Romania, saying a covert goodbye to her parents. (“Don’t be worried,” she told me she’d said, “if you don’t hear from me again.”) She’d wanted to live in America but had gone first to France, not realizing that you can seek asylum only once. She’d had trouble getting her writing published in part, she said, because she wrote and thought in three languages: Romanian, French, and English. Her English was flawless.

One day we snuck out of the colloquium into the gray relentless rain of Paris in March to go to a designer sample sale, trying on clothes and buying nothing, and again to escape the university lunch of water crackers with microscopic bits of meats and cheeses, and off to a café where we ordered giant salads drowning in crème fraiche. For three days we were best friends. She vowed she was coming to visit New York in the fall, though I knew, and suspect she did too, that she wouldn’t. Sometimes we email. Before I left Paris, she handed me a cellophane-wrapped soap with an exuberant daisy in the middle. I keep it on my dresser; it’s too good to wash with.

When the children were small, almost every night when the weather was good, or simply good enough, I used to meet three other women in the park. We met around seven, after work. Our husbands were working later than we were — two were chefs in restaurant kitchens half the night. Exhausted from babies and toddlers and jobs and laundry and dishes that did not end, we’d heave our kids into the baby swings and push them and push them and pull them out — Brendan’s toddler cowboy boots would catch in the swing’s leg holes — and help them up ladders and into and out of wide plastic tunnels and chase them as they chased after fireflies across the open lawn. These weren’t the alpha moms who would soon appear in town, angling their $800 strollers into the new Starbucks. We dressed in sweats and leggings and oversized Ts. No one worked in publishing, as I did, or trafficked in words. These were women who, had my children been born in an ever so slightly different time or place, I would never have met: a chef, a chef, a caterer/potter. I think they saved my life.

We’d stay until well after darkness fell in the park or else leave to get what might have been the world’s worst pizza (fake cheese, tasteless — but the owner tolerated, with minimal dirty looks, our noise and detritus). One Christmas eve, two of the women, with their husbands who were, for once, not working in restaurants, converged at our house. (Imagine the pressure of cooking for that many professional chefs — in an act of cowardice, I let my husband do it.) The five kids under six didn’t last long at the table, seized as they were by the kind of anticipatory frenzy that is usually only possible in the very young. I’m sure there was a great mess and that we were dead tired, but what I remember are the children shrieking in delight. I also remember the other two women, trained in restaurant kitchens, converging on mine like a SWAT team; I have never seen anyone deep-clean anything so fast.

What happened in the following year was school. Boys played with boys, and girls with girls. We had homework now, and sensible bedtimes. C, the potter, moved farther than walking distance, to a house where she had her own kiln. Little by little, the park nights stopped.

The other three women are now divorced. K left town. T, I see rarely — we wave when we pass. Every so often, though, I hang out with C, the potter whose skinny boy is now a well-built, tall young man. We lost a mutual friend last year, at 50, to cancer, a woman whose son is the same age as ours. C still throws in her kiln-equipped basement — bowls, vases, and dishes that she sells in Manhattan. I’ve bought several of her graceful blue and green serving pieces. But C knows the ones I like best are the $5 seconds — the ones she can’t sell in stores: The glaze has dripped and bubbled, the clay shows in patches, the color, when baked, turned wonderfully strange. Perfection is sometimes the enemy of good. Besides, I like a lucky accident.

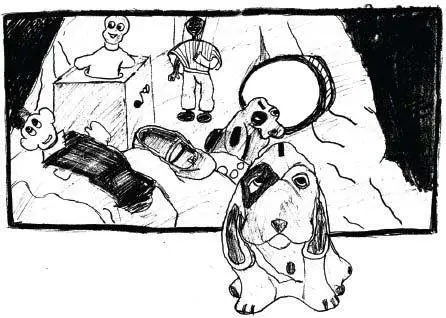

My mother painted a still life in acrylic of my toys when I was four: a marionette, a red-and-white striped tin drum, a jack-in-the-box from which the clown had sprung, a pink ballet slipper — though I have no recollection of taking ballet at that age — and the Florsheim dog, all set against the backdrop of my blue baby blanket. The dog, a gray, long-eared, adorably dolorous hound, was the logo for the Florsheim shoes that my grandfather sold; this particular Florsheim dog was not a toy but a piggy — or doggie — bank. It was plastic, covered in some indeterminate fuzzy material. I kept my pennies there. A few stray pennies are spread on the blanket in the painting.

My mother’s composition went into storage from the time I was around nine until Brendan was born. Until recently it hung in the room he shared with Sean. Occasionally, I’d ask whether they were ready for me to take it down; they weren’t. We put it away only when we were starting renovation of that room.

Читать дальше