The children’s nanny was the other woman in my house. D came from Trinidad, one of nine children; her own mother, she told me, had married at 14. (I interviewed many nannies and will confess now that what clinched the deal was not only D’s abundant warmth and her enthusiastic references but also her answer when I asked: What do babies dream about? Several nanny candidates were flummoxed by that. D’s answer, without missing a beat, was that her mother told her babies dream of angels — which told me that D didn’t find unanswerable questions irksome or absurd.) Although she was not much older than I, her daughter was in college (and would become a lawyer); her son was 10 and in school.

Because D knew my children in the most

intimate way, knew the way they smelled as babies, the feel of their skin, the heft of their bodies — asleep, awake, jumping — she seemed to know my heart. And she certainly knew my house, its needs and its wants and its lapses. She knew I kept my jewelry in a battered old box that I didn’t bother to replace, the way I didn’t bother to replace so many

old and broken things when there was so much to be bought and done for and taught to the children. In nine years she missed maybe four days of work — unless it was Divali, when she would bring over fragrant Indian food, roti and samosas and fish wrapped in foil. She spoiled my children and loved them too, and her husband ruined their appetites by bringing them candy and chips before dinner. She was surely more patient than I, and quicker to laugh, and better at artful arrangements of just about anything. I never wanted our arrangement — this feminine partnership in my home — to end, but of course it had to; the children were in school all day. She left the month after my mother died.

Now she calls and I call and we visit and she remembers the day my father died and the way the kids both daydream (one on his feet, the other with his pencil) but it’s not the same. The chair she liked to sit in most is broken. She was better than I am, my children remind me, at making Cream of Wheat and also singing. I miss her easy laughter and her lilting Island voice. I keep my finest jewels in the box she bought for me.

While my Grandfather Bern’s tastes were simple, my Grandmother Bern liked elegant old things and she would go to auctions to find them — end tables and porcelain urns and pretty rugs and lamps. By the time my grandparents were moving from the apartment where they’d raised my mother and uncle to a one-bedroom, my grandmother had amassed a collection of real Oriental rugs that she couldn’t take with her.

My mother didn’t want them. She liked everything modern: white leather, white carpet, chrome and glass. And so the only rug that stayed in the family was a tiny Oriental rectangle that sat under my grandmother’s tea cart at the mouth of her galley kitchen. The cart was used to hold dishes to be brought to the little eating nook or to wheel demi-glasses of tomato juice with lemon out to the metal folding table set up in the living room for Thanksgiving dinner.

My grandmother loved to cook and bake — from that cramped kitchen emerged paprika chicken with mushrooms and rice, lamb chops with jelly, key lime pie, lemon meringue, pineapple strudel, sponge cake and chocolate cake, layered and frosted and studded with walnuts. She would feed us and fuss, and each time we said goodbye, tears welled in her eyes. Sometimes she would mail us food she’d made.

My mother put cooking in the same box as old furniture and religious ritual — something oppressive, from a generation where women were subservient. She liked to remind me that her own grandmother had died of a heart attack while standing in a hot kitchen making Rosh Hashanah dinner. She would point out her mother’s ankles swelling over the tops of her shoes as she stood at the counter chopping nuts or over the burner boiling dumplings. My mother wanted out with the old — the old country ways, old habits, obligations, dark and heavy furnishings, things that looked traditional or, worse, antique. Still, after my grandmother died and my grandfather moved out to California, my mother brought home that tiny rug, and she often lamented that she’d let the others go. She brought home her mother’s monogrammed purses (her own initials, always, not those of some designer), her gloves, her pinned hats. Her glassware and dishes, although they were heavily chipped. Her ornate gold watch, which my mother never wore (“After I die,” my mother said, “take it to New York and sell it.” But my sister wanted it, although she never wears it either.) I believe those rugs were the only things she had given away and wished she’d had back. The sole remaining one went in my mother’s downstairs bathroom — there really wasn’t any other place for it in her white/glass/chrome suburban townhouse. It got threadbare.

Emptying my mother’s desk and dresser drawers after her death, I found notes everywhere, addressed to me and to my sister, having to do with what she wanted done with her possessions. Some of these notes must have been 20 years old, judging by the faded ink and by the fact that they referred to people long deceased as if they were alive. Some were more recent. All where handwritten. One of them instructed me to take the Oriental rug.

I had given that rug no thought at all and had no idea what to do with it. But here was my mother, dead, and still talking to me. I didn’t dare leave it, didn’t dare give it away. Right now the rug is under the desk in the office where I write.

When my father left my mother, he started to travel. The metal sculpture of the fisherman from Mexico was a divorce appeasement gift to me. I was 15 and angry — with pretty much everyone. And yet, that sculpture followed me to umpteen dormitory rooms and apartments, walk-ups, sublets, roach motels.

Now they are both dead, my father and my mother. And I still love that fisherman, waiting for the catch.

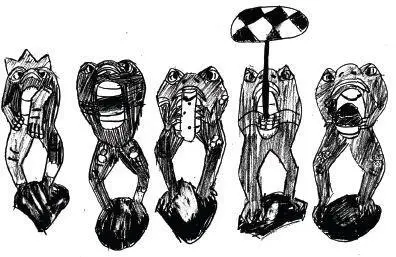

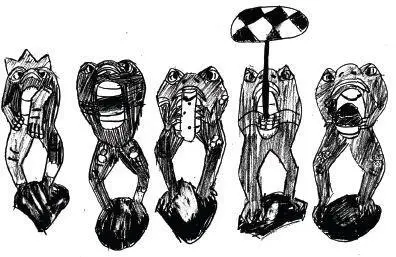

My husband saw me looking in the window of a store at five wooden Balinese frogs, each playing a musical instrument. A week later, on our anniversary, those frogs were on our bed. This is why we’re married.

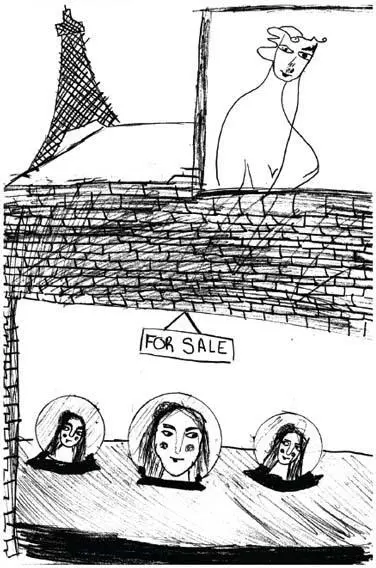

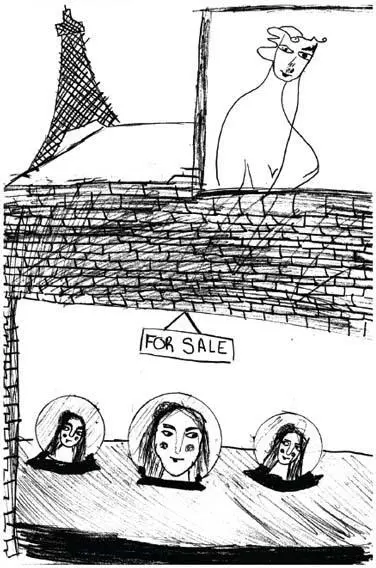

My first job in New York was at a magazine where a frail, elderly man delivered the interoffice mail. Over time it emerged that he was an artist and had in fact made the spare, expressive paintings that were hanging in the magazine’s corridors. He spoke very little but I often noticed him looking intently at me. Once I heard him say, “Very French.”

One day he dropped off a drawing at my desk, told me that he had made it for me and walked away, embarrassed. The drawing, rendered in just a few dark strokes, was of a woman’s face, and though it was not particularly representational, there was something unnervingly familiar in the cast of her eyes and the set of her mouth.

I left the magazine soon afterward and never saw that man again. A few years later, my future husband took one look at the drawing, which I’d had framed, and said, “That is definitely you.”

We went to Paris for our honeymoon and again for our twentieth anniversary. Leaving our hotel in the Place St. Germain every morning, we passed a pottery shop. In the window was a set of bowls; painted inside each was a woman’s face that looked to me strikingly like the face in the drawing hanging over the fuse box at home. I said nothing about it. After we’d walked past a few more times, my husband said, “It’s odd, isn’t it, seeing your young face in that window.”

Читать дальше