My grandfather’s concession to American Christmas was to place in the store a small glazed porcelain tree that plugged into an outlet, kindling its colored lights. My mother loved that tree. She ferreted it home to Milwaukee when my grandfather closed the store for the last time — though it never left the basement. My sister has it now.

My husband met my grandfather just once, during what was both the summer before our wedding and the final summer of my grandfather’s life. In L.A. on business, Mike took my grandfather and his wife, Elsie, out to dinner.

“What are you having, Bert?” Elsie said.

“You know I can’t read the menu!” he said. “I’m waiting for you to tell me!”

If my 91-year-old grandfather was close to blind, Elsie’s vision wasn’t much better. And though her hearing was fine, she had developed the habit of shouting to penetrate my grandfather’s neardeafness. Not far from their table, my husband said, was a woman in a low-cut dress. “Look, Bert,” Elsie yelled as they were winding up their meal, “she’s naked!” My grandfather let Elsie walk out of the restaurant ahead of him and took his Irish Catholic future son-in-law, whose wedding he would not live to see, by the arm. “Let’s go back,” he said to Mike, “and have another look.”

We named our first child for him. (Given that my grandfather had changed his name from Bernard to Bert, I felt justified in changing it to Brendan.)

Every year at Christmas, my husband and our sons, Brendan and Sean, drive north to the woods to cut down a tree, which we decorate with boxes of ornaments and yards and yards of lights, including the bubbling 1950s kind from his parents’ house. We have an angel in the window, stockings on the stairs, and three menorahs in the kitchen. We also have a china tree from CVS, one-foot high, with tiny bulbs, just like the one my grandfather had.

My father was stationed on Guam during World War II. He’d been an engineering student at Marquette University at the time the war broke out. When he was drafted, the army sent him for advanced training at Harvard — the big band leader, Glenn Miller, who would die overseas, used to play for the troops during drills — and then, with the top two percent of his Harvard class, to the rad lab at MIT. He landed on Guam with the initial deployment from the Air Corps, and was part of the team who built the first radar.

Unknown to anyone, my father had a congenital, degenerative disease of the middle ear that caused his hearing to be destroyed by the noise on the air base where he serviced warplanes. By the time he visited Japan after the armistice, he was functionally deaf and would remain so for almost 20 years. He used a large hearing aid that whistled feedback until the early 1960s when the ruined bones of his middle ear were replaced with Teflon. Nevertheless, at the time he visited Japan, he perceived an unrestricted future; he was about to return home from war and begin a career in aeronautics, for which he’d developed a passion.

My father had some of the most advanced training in the world, but he had underestimated the degree of anti-Semitism in this country after the war, especially in the engineering field. He received one job offer, which was rescinded after he filled out a form in which he was asked to state his religion. (My father’s uncle, faced with the same problem, changed his name, moved to another city, joined a church, became an engineer, and never told his new family he was Jewish. My sister remembers going to his daughter’s wedding as a child and being sworn to secrecy on the topic of religion; years later, one of his granddaughters tracked me down online, trying to learn her family history.)

My father went to work, wearing his hearing aid, in his father’s family furniture store; he spent his days selling LazyBoy recliners and Philco appliances and Lane end tables, and his spare time in the basement on his homemade ham radio, communicating, often in Morse Code, with people thousands of miles away (his call signal was W9QCJ and I can still recall him saying it—“Queen, Charlie, Japan”) and reading up on physics and astronomy. All that remained of my father’s war years were the rank-smelling uniforms hanging in the basement and the red tea set.

I don’t think my father was especially unhappy; he was someone who could coax an adventure from just about any set of circumstances. (Some of his escapades were less than practical. The $19 inflatable boat deflated in Lake Michigan; we swam back. Allowing me, at nine, to steer the Cessna he had rented in exchange for a loveseat nearly resulted in loop-de-loop; we never told my mother.) After his hearing was restored, he adored music and dance. But there was always, for the rest of his life, I thought, a shadow, or a hint of disturbance — something sensed in a stray aside or silence.

At some point he gave the tea set to me. Now it sits in my china cabinet. To the best of my knowledge, it has never been used.

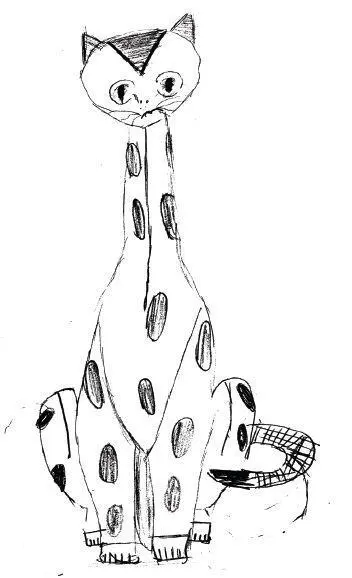

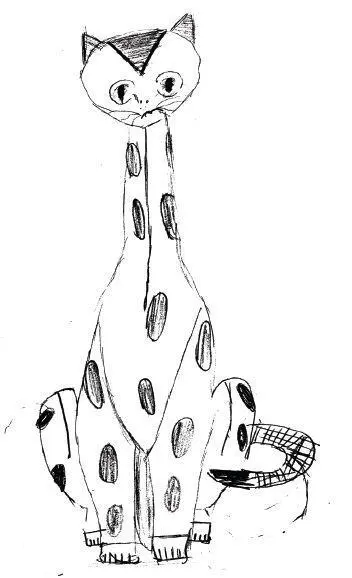

The black and white china cat sat on my Grandmother Raffel’s window ledge all the years she was an invalid. The cat seemed to watch the world through glass. When she was younger, my grandmother raised two boys, kept the books for the family furniture store, held office at half the clubs in town, melted her silver down for the war, survived the telegram telling her one of her sons was badly injured (it was my uncle, who’d broken his back parachuting out of a burning plane; his cousin would soon be dead), read the entire library of Reader’s Digest condensed books, entertained her many friends often and enthusiastically despite being — forgive me — an inattentive cook (she burned frozen entrees by forgetting them in the oven; neglected to buy ingredients for baking and substituted anything at hand, such as Smucker’s jelly for cake frosting; made Jell-O molds that failed to gel and wept in festive red and green and yellow pools on platters, forlorn chunks of fruit bobbing up… nobody came for the food). She thought nothing of taking three or four or five of her grandchildren to an amusement park for the day, or out for Chinese New Year, such as it was in Milwaukee in the 1960s, (neon drinks adorned with paper parasols; celery-heavy chop suey), or on a boat ride, or to the theater (she insisted on front row seats) or to hear music under the stars. I have two pictures of my grandmother. In one, she is striding purposefully down the street while snapped in a 1930s candid, her gaze intent and confident; in another, she is in a rowboat with my grandfather and she is the one rowing. She wielded fierce opinions on everything from politics (she cast an absentee ballot for Richard Nixon, then died of a heart attack the week before the election) to hot pants on girls (she was in favor and wanted to know why I wasn’t wearing them).

By her late sixties, she was largely confined by heart disease to her house. On Sunday nights, she marked up the TV Guide for the week — talk shows, news, no soaps. My grandfather continued to work, long past retirement age, in the furniture store, and to sneak out on occasion in the evenings to the Big Boy for strawberry pie. The phone rarely rang.

My grandmother’s last few years went in a circuit from the bed to the TV chair to the kitchen and back to the bed. “They shoot horses, don’t they,” she said.

I had the cat on top of my china cabinet when my older son, born 30 years after her death, asked me about it. Then he reached up for the cat and put it in the window, facing out.

Читать дальше