The trip to Greece was an accident, a mishap, the result of a miscommunication that would not have occurred in the age of email. It was the end of 1977; I was going to visit my friend C in London and she wrote asking whether I would like to take a brief side trip, say, to Scotland. I wrote back and said yes. When I arrived in London, C told me she had found a deal on sunny Athens and since there had been no time to write back and forth, she had already purchased our nonrefundable airline tickets.

Athens was not sunny, not in terms of weather or general atmosphere — it was a military dictatorship — and not in terms of my mood either. We were broke and I can’t say that I was a very good sport. We froze in a rented room we’d found late at night, having landed in Athens with no plan of action, then moved to a YMCA where we shared a not-much-warmer room with eight other women and one sorry toilet. The ruins, distracted as we were, were hard to comprehend. What food we could afford was cheap and greasy or gristled. Delphi, arrived at by rickety bus, was gorgeous — I remember sitting on the crest of a hill overlooking a sweeping expanse of greenery, eating goat’s milk yogurt on a cloudless day — but mostly we were hungry and cold. (The fault lay not in the least with Greece or its citizens. One day we were invited off the street into an elderly woman’s home for cookies, and another day into a church to view the end of a wedding. I shudder to think what would have happened if we had approached New York in a similar manner.) Back in Athens for New Year’s Eve we tried to extend a coffee in a café until midnight but found ourselves back on the street with more than an hour to go. Everywhere we went, we were accosted by men who assumed two women alone were whores, or at the least, fair game.

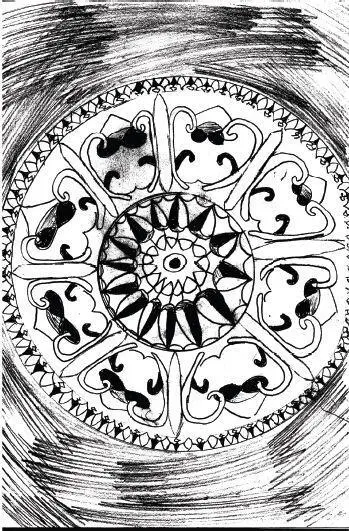

I bought one thing in Greece: a cloisonné plate — my mother had taught me to appreciate that art, in which luminous fragments redound to a whole — in red and green and gold, in rings of starburst. What I paid I can’t recall, although I do remember standing in the store and thinking that the plate was remarkably inexpensive, and worth skipping a meal. I took a redeye back to London (C stayed in Greece), then stood outdoors in sub-freezing weather for more than four hours waiting to get a seat home on Laker Airlines that, in turn, was seven hours late to JFK. By the time I got back to college in Rhode Island, I was on the brink of being sicker than I’d ever been in my life, or have been since — shaking with fever, irrational, unable to manage food for days. (C, I later learned, was equally sick in the Y in Greece). I ended a relationship precipitously out of utter confusion and stayed in my room. I had brought home a handful of snapshots, many blurred, a teacup from London, a cloisonné plate. I vaguely remember somebody using the latter, much to my dismay, as an ashtray.

Thirty years later I found in a box marked “Dawn” in my mother’s basement — along with my plastic-bound thesis, my yearbook, a pile of spiral notebooks, and my bachelor’s degree — that shining plate. These artifacts are of a time that in many ways I would rather forget — a piece of my life that was not of a piece with the rest. Between 20 and 22, I was too often carelessly unkind, and also often despairing. That I belonged nowhere, geographically or emotionally, makes those years hard to light, even in the flattering incandescence of memory.

And yet I am glad that my mother saved that vision in fragments. It belongs to me.

What My Mother Thought She Had Lost That I Found

1. A lot of her jewelry. She’d called me, tremendously upset, believing that it had been stolen. I found it in a white trash bag in the back of the closet, hidden, I suspect, out of fear of theft. I also found the earrings that go with the crystal necklace that I wear all the time.

2. The deeds to the gravesites. They were in the attic.

There were two matching vases in my mother’s downstairs bathroom — a big one and a little one. I took the little one and left the big one in the house for the resellers to sell. Why did I do that?

He was my Grandfather Bern’s brother, one of the younger siblings who was brought over with his parents from Kisvárda, Hungary by — depending on who you believed — either my grandfather or his older sister. Another brother had died in the great influenza epidemic that had swept through Europe in the second decade of the Twentieth Century; others had not survived childhood. Irving made a fortune and died in middle age, of a heart attack over dinner in a restaurant with his wife, my great aunt L.

I met him only twice. The first time, I was four. He gave me a red china devil with a pipe cleaner tail and a fireman’s hat slung on a chain around its neck. When I was nine he gave me a bag of cosmetics (beauty being one of his businesses). When I was eleven years old, he died; I was inconsolable. (Great Aunt L, who went on to be widowed again, was diagnosed with depression; by the time someone figured out that her fatigue and pain were, in fact, caused by cancer, it had already metastasized.)

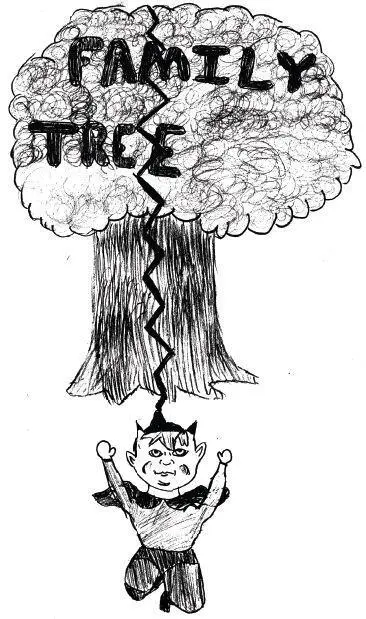

My mother kept up with his children — her cousins — for a while, and then that branch of the family simply dropped off like a piece of a continent into a sea.

My grandparents’ generation — often short of space and short of temper; they fought robustly — would cram around metal folding tables, finding occasions to meet. Their descendants moved on, all over the country; we, as we say, “lost touch.” In this, our family is by no means unique; witness the popularity of reunion websites. But what one finds online — the satisfaction of scratching a certain curious itch — doesn’t salve a thirty- or forty-year lapse.

For all that my mother accrued in material possessions, her most prized collection was of people — of cousins, of “once-removeds,” of friends. She had dozens of genuine friendships — not acquaintanceships — that lasted for decades. These were not colleagues; no one was networking. No one had girls’ getaways, pre-packaged. Instead, they had the phone — rotary, princess, cordless, cell. They had the car for the afternoon. These relationships were messy and complicated. Many of the women — all “Mrs.” to me, until I went to college — are dead now. Their kids, who once piled with me into backseats of cars, are all over the country, all over the world, as are the snapped-off branches of my family.

I have a little devil.

We bought our house from a man who’d been living there with both his lover and his mother. When his mother died he was getting ready to fix up the place to put it on the market; we offered to buy it as-is. This meant that nothing had been repaired or repainted (the ghost of a Dustbuster past haunted the kitchen wall; he had apparently painted around the device). Various items remained in the house. Some, such as the old stuffed chair in the sitting room where I sat and nursed my babies in the night, were deliberate leave-behinds, furnishings he told us he no longer needed. Others took a while to find, including the silver medals of saints stuck in odd spots on the walls.

Both of the apartments where I had lived with my husband in Manhattan had been refurbished and delivered as if new. But in our house, it is impossible not to notice that other lives have been lived within its walls. The previous owner’s mother, for all we know, died here; if not, then she was certainly dying, surrounded by emblems of faith.

Читать дальше