* * *

The handsome oak room is populated with men of commerce who customarily refuse the possibility of consensus, preferring instead to become heated with their own opinions, which they proclaim with a confident swagger calculated to override both logic and consideration. Their chief topic of interest is the fluctuating prices of sugar, rum, and slaves on the Exchange Flags, but on this blustery evening, the working day having been concluded, pipes and tobacco and newspapers and punch are much in vogue at the Kingston Coffee House, and no further industry is being conducted, as the men now sprawl with books bound in soft leather and stretch out before the fire. A jaded lodger, keen to impress upon onlookers the idea that no man need greet him cordially, sits at a table towards the rear of the room. Before him a knife is embedded in a slab of meat and candlelight plays on a silver goblet, and a rush of uncertain sensations courses through his body. Earlier in the evening, the landlord had set him down for an ass. After he had paid the man his money, the drunkard furrowed his brow in mock confusion and insisted there were no personal effects and claimed that he could offer no information with respect to the child.

His child. At the conclusion of their second dinner she slipped off her dress in the backroom of the Queen’s Head tavern, and his heart fell when he saw that she had been branded with the initials of another man. Suddenly he felt only tolerably well, and he became aware of tightness in his lips, and then his face began to colour and quiver uncontrollably. Once their enterprise was terminated, his conscience remained unsullied with regret, for although their union had not been sealed with missives sent by Cupid’s post, he had not stooped to using her brutally, and he understood that his wife would never inquire of him regarding time expended in Liverpool. Two days later he began the return journey across the moors, but long before he reached home, his mind had already turned back to Liverpool and thoughts of again entertaining this woman, who seemed willing to establish an arrangement by which she might call upon him at the Queen’s Head tavern whenever he had commerce to conduct in the town she now called home.

A year later their child was born. When she asked of him if he might arrange for her and the boy to return to the trafficking islands, he happily went in search of a captain he might trust. However, he soon divined them all to be testy, irritable creatures who tendered him no assurances that once at a distance from the laws of the land they would not use her and the boy heartlessly, and so he offered the woman money in exchange for the convenience of continuing their arrangement and sparing his soul the burden of worrying that he might have dispatched them both to a sad fate. But what hope now for the boy on the streets of this town? He knows full well that it will be only a matter of time before the child is propositioned with a tot of rum and overwhelmed and pressed to serve as a prize upon one of His Majesty’s ships, or else accused of thievery and snatched up and spirited away to a workhouse.

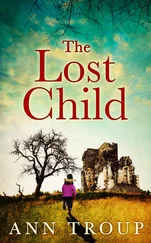

At the first light of dawn he leaves the Kingston Coffee House and makes his weary way to the docks. He stares intently at the bold shield of the moon that is still conspicuous in the sky, and he speculates that it must be the pulse of the sea that anchors the moon to the heavens and prevents it from wandering. At this hour of the morning the slumbering town appears ready to slide gracefully beneath the surface of the water and disappear from view. He mumbles to himself. And God’s cleansing shall be visited upon all. He looks out at the miscellany of docks that are carelessly cluttered with a jumble of masts and sails, swaying first one way, then back again. These murmuring pools are flecked with rotting debris, and the water is combed by the wind, gurgling and puckering when the breeze rises and then abruptly settling as though someone has swiftly drawn a thin oily skin across the surface and whispered, be still. The black-haired child is asleep but fitfully twitching, and then his eyes slowly open. Even at this tender age his sombre aspect suggests an abundance of pride. There is a luminosity to the boy, as though he is cognizant of something that others cannot see, and this knowledge bequeaths upon him a full awareness of his destiny. Come to me, young lad. We have no business meddling in the affairs of heaven. Come to me, son, and let’s go home.

The rain continues to beat frantically against the window, and the peals of thunder grow menacing as though the storm is now passing immediately overhead. The frightened boy sits on the edge of the chair, but he refuses to look at the man with whom he is travelling, preferring instead to stare at the space between his muddied feet. Occasionally the boy throws a glance in the direction of the fireplace, as though he expects to find an answer to his predicament hidden away in the heart of the flames, but he quickly returns his troubled gaze to the floor. The man looks hopefully in the boy’s direction, and then he leans over to touch his arm, but the boy pulls away and casts him a look that is freighted with contempt.

The man had surmised that it would be possible for them to reach their destination before the storm broke. When they began their journey the first rumblings of the squall could be heard in the very far distance. The man gestured proudly to the gorse-stubbled landscape as though he owned it, pointing out birds and small animals and flowers and baptizing them with names that he was eager the boy should remember. However, before they had ascended the first gentle peak, the low, fast-moving clouds had bathed the whole moor in shadow, and it was apparent that the man had underestimated both the fierce weather and his own tired state. Once the driving rain began to lash down in earnest the man peered desperately into the gloom for any sign of a farmhouse or barn where they might find shelter. After struggling against the strengthening wind for what seemed like an eternity, he eventually made out a single light in a distant window and attempted to quicken his step, but he realized that he was in danger of leaving the boy behind. He stopped and took the distressed lad firmly by the arm, and with his free hand he brushed the rain from the child’s eyes and began now to drag him through the rumpus.

The stranger opened the door to his cottage and looked at the uneven apparition of man and boy that greeted him. The flustered man’s dripping clothes suggested some status in this world, but the ill-dressed child seemed adrift and lost. It occurred to the stranger that this boy might have been discovered upon the moors, a runaway of some sort, and perhaps the connection between the two had been forged in the adversity of this calamitous unrest. There was no time for speculation, however, for the wind was howling, and it took what little strength he possessed to hold open the door against the turbulence of the gale. The stranger stood to one side in order that his visitors might step clear of the gravel footpath and enter, and he watched as the nervous man gently pushed the boy ahead of him.

As the stranger closed in the door behind them, the man quickly removed his sodden jacket, but he decided not to suggest to the boy that he do the same. Instead, he surveyed their grey-bristled host, who was tall and gaunt and who looked as though nature had carved his dull features from the bark of a gnarled tree. The man noticed that there was moist life in the stranger’s dancing eyes, and a firmness to his handshake that defied his accumulation of years. He assumed that he was possibly a farmer of some kind, a stubborn fellow who scratched a meagre living from a carefully demarcated piece of rutted earth. Tending to sheep, and conceivably a few cattle, with some attempt made to raise poultry and collect eggs, most likely constituted the extent of this man’s lean agricultural world. No doubt the solitary rhythm of his life would be interrupted each Sunday, when the stranger would wash and change and reach for his Bible and stride across the moors to the village church, where he would be temporarily reacquainted with others in the human family. Thereafter he would probably return and quietly resume the bleak routine of his existence and simply wait for Sunday to once again announce itself.

Читать дальше