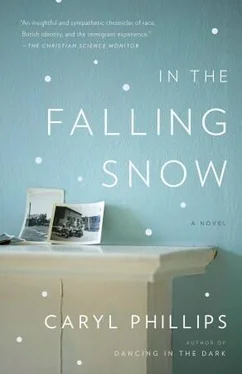

Caryl Phillips

In the Falling Snow

The streets of modern-day London are hectic, multicultural, and difficult to read if you are a white-collar, middle-aged man. Keith is a social worker who, following a brief affair with a colleague, finds himself living alone in a flat a few streets away from his wife, Annabelle, and his teenage son. His domestic problems, allied with growing tensions at work, profoundly undermine his peace of mind. Keith attempts to take refuge in a long-cherished writing project and turns his attention to the plight of his ageing father, but for the first time in his life he feels extremely vulnerable as a black man in English society.

Annabelle met Keith twenty-five years ago at university, and she watches the man she married — against the wishes of her English parents — as he appears to be losing his grip on his life. However, after three years of estrangement, she realises that despite her disappointment with her former husband, the pair of them have no choice but to close ranks and protect their son, who seems to have become increasingly involved with street gangs and a world that is entirely alien to them.

A brilliant and penetrating story of contemporary Britain, In the Falling Snow is Caryl Phillips’ finest novel yet.

Caryl Phillips was born in St Kitts and now lives in London and New York. He has written for television, radio, theatre and cinema and is the author of twelve works of fiction and non-fiction. Crossing the River was shortlisted for the 1993 Booker Prize and Caryl Phillips has won the Martin Luther King Memorial Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, as well as being named the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year 1992 and one of the Best of Young British Writers 1993. A Distant Shore won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize in 2004 and Dancing in the Dark was shortlisted in 2006.

www.carylphillips.com

HE IS WALKING in one of those leafy suburbs of London where the presence of a man like him still attracts curious half-glances. His jacket and tie encourage a few of the passers-by to relax a little, but he can see that others are actively suppressing the urge to cross the road. It is painfully clear that, as far as some people are concerned, he simply doesn’t belong in this part of the city.

As he turns into Sutherland Road, he reaches up and peels off the dark glasses. There is no sun to speak of, and autumn has long ago dispatched the lukewarm summer for another year. The wind suddenly rises and dislodges a flurry of leaves from the overhanging trees, and he feels a chill ripple through his body. Despite the cold, the dark glasses make him feel more comfortable on these streets, for he is able to look at people without them being able to see his eyes. He fishes the slim plastic envelope from his inside jacket pocket and folds the glasses into their case, before tucking the envelope back into the same pocket. He stops by the small gate and takes a deep breath, and then he reaches down and lifts the latch. He passes through and watches as the wooden contraption swings back into place with the assistance of a tightly coiled iron spring. The half-dozen steps along the crazy-paved pathway are undertaken joylessly, and then he pushes the bell, which sings out with a lyrical two-toned peal whose lingering echo suggests that nobody is at home. He hears footsteps padding down the stairs, and he listens as she fiddles with the bolt and chain before throwing open the door.

‘Keith?’

He is never sure what to make of the greeting. It is not really a question, for they both know who he is.

‘You all right, Keith?’

He says nothing in reply. She tosses back her tangle of black hair and tilts her chin upwards, and then she quickly tips her head to one side and invites him to kiss her on the cheek. He leans in and dry-kisses her, and then as he stands tall he lets the end of his tongue draw a wet line against the side of her face.

‘Dirty sod.’

‘What do you mean, “dirty”?’

She laughs out loud.

‘I’m only kidding. You look good, babe.’

He steps through the door and notices her looking anxiously over his shoulder to make sure that there are no prying eyes, and then he hears what he imagines is a businesswoman hurrying by whose footsteps click primly against the pavement. She slams the door shut and he resigns himself to the fact that once again he is marooned in her dismal hallway, at the bottom of her stairs, in her small terraced house in north-west London.

He watches as the late afternoon light fades behind the sky blue curtains. She should use heavier fabric in the bedroom. At first he stayed overnight, and in the morning, as the birds started to sing, he would lie quietly beside her and wonder if his wife was also waking up next to somebody else. And, if she was, where was their son? Who was looking out for Laurie? In the mornings he tried hard not to move as the last thing he needed was Yvette talking to him, but because the curtains didn’t block out the light it was impossible for him to sleep beyond dawn. He thought maybe she liked it this way, with nature giving her an automatic wake-up call, but he didn’t want to ask any questions because that would be to suggest an intimacy that he was keen to avoid. A forty-seven-year-old man and a twenty-six-year-old girl. He understood the detached role that he was playing, and he was determined to stay in character.

These days there is a predictable pattern to these more acceptable afternoon visits. Yvette likes to take charge. She carefully turns out the light in the downstairs hallway, and then she leads him upstairs. Once they reach the top landing she lets the silk robe slip to the floor. Initially he found the drama arousing, thrillingly so, but after his third or fourth afternoon visit (or ‘service call’ as she likes to refer to them) she abandoned the black lace corset that he relished and replaced it with a red push-up bra and a matching thong. Clearly she imagined this to be an improvement — more of a ‘turn on’ — but he couldn’t find the words to fully express his disdain for the crass vulgarity of this silly piece of string. Yvette continues to wear this tart’s uniform, and as her robe pools on to the floor his eyes drop down and focus first on her legs and then on her ankles (which he knows are cocoa butter smooth), but try as he might he can’t bring himself to look at her underwear. Once inside the bedroom, Yvette locks the door by sliding a small brass bolt into place, and then she eases her hands into his jacket and up towards his shoulder pads, stripping the garment from him as though peeling the skin from a piece of fruit. He may not have found a way to talk with her about the underwear, but he has been forced to tell her that scented candles make him gag. After the second coughing fit, Yvette quizzed him, and although at first he denied that there was a problem he eventually confessed, and she laughed and assured him that a hint of jasmine or honey peach was something that she could happily live without. Having removed his jacket she allows him to undress himself while she lies on the top sheet of the bed and unclips her bra so that her breasts, while not totally abandoning the infrastructure of the wired cups, perch mischievously on the threshold of liberation.

Yvette’s enthusiasm is almost theatrical, but she is genuinely aroused and achieves a climax with speed and great vocal excitement. He used to worry about the neighbours, but she assured him that they seldom returned home from work before nine o’clock. Besides, she and Colin never had any complaints from them, and she never hears their lovemaking, so she assumes that the walls between these houses must be quite thick. She closes her eyes, lies back on the bed and continues to catch her breath, while he props himself up on one elbow and carefully tunnels his free hand through the rough nest of her hair. He knows that she ‘relaxes’ it, for he has seen the full artillery of creams and lotions in the bathroom, but her heritage is most evident in the battle between Europe and Africa that is being waged on her face where full lips and emerald green eyes compete for attention. Under the most intense scrutiny she could easily pass for white and suntanned, but her penchant for kente cloth scarves and wooden beads speaks eloquently to the fact that she has never tried to deny her mixed background.

Читать дальше

![Unknown - [Carly Phillips] The Bachelor (The Chandler Brothe(Bookos.org) (1)](/books/174132/unknown-carly-phillips-the-bachelor-the-chandle-thumb.webp)