The chief engineer massaged his hands. She saw that his face was changing, saw that minor and moderate storm floods were visibly giving way to something more drastic, and here it came: “The third category that we distinguish is the high storm flood. A frequent phenomenon? No. Occurs merely once every hundred to a thousand years. Good, I see you’re nodding. The Hydraulic Authorities have never actually measured one as such, let alone broken it down into accurate statistics.”

He paused for a moment. Then, with a kind of enthusiasm that mystified her, he explained that science did recognize a supreme category of storm tide, a four-star ranking, signifying a catastrophe that, however unlikely, could not be written off as impossible just because it might occur in this part of the world every ten thousand years.

He leaned forward with his head and mouthed something, but she didn’t understand.

“Sorry?” she asked, and the answer came in a roar.

“The extreme storm flood! Oh! Can you just imagine it? Have you never heard anything about the hellish catastrophes in the old days? The Saint Elisabeth’s flood in the fifteenth century, that swallowed up our entire province of South Holland? A century later: Saint Felix, even worse, a storm that felt called upon to restore all the mussels and crabs to the twenty villages around Reimerswaal in perpetuity. And then, darn it, forty years later, in the blink of an eye, statistically speaking, enter the All Saints Flood, and people are thinking all over again that it’s the end of the world!”

The chief engineer laughed for a moment. Then: “Nature’s fits of rage, every one of them responsible for enormous numbers of deaths!” Did she also grasp that this entire spectacle often ran its course with such extreme results not merely by force of nature but because of the shiftless maintenance of the dikes? Only a mountain contained its own mass unaided. Please would she believe him if he assured her — it was clear that he wanted to utter some unvarnished truth, the kind that makes your ears prick up — assured her as an insider, that the crests of the dikes even today failed to meet the norm?

He was looking at her with the peremptoriness of a man who knows the figures pretty damn well.

“Umm … you’re a nice young lady. Am I alarming you?”

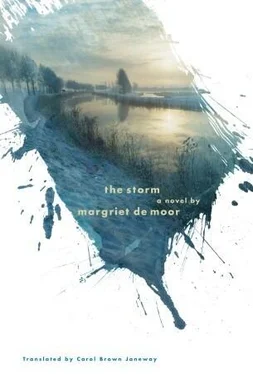

Not at all, though now her eyes were fixed on something else. A little ship, tiny in fact. It was about sixty yards away, chugging along in the opposite direction. She squeezed her eyes shut. Sometimes it disappeared up to the wheelhouse in the waves, and then she would be able to see the black tarpaulin and read the name, Compassion , before it plunged back into the depths. Rays of light piercing down through the cloud formations gave the scene a theatrical air.

“I … think it’s really beautiful.”

“Indeed, it’s impressive,” the chief engineer admitted. Then, after a pause: “Cosmic and earthly powers from unimaginably distant regions are converging right in front of us.”

She gave a searching look into his slightly bloodshot eyes. He wasn’t grinning.

“Lofty words.”

“Am I boring you?”

“Absolutely not. Actually, this is my first time here.” And like someone who in a chance moment recognizes that the heavens are the eternal, everlasting, primeval landscape of our minds, she said, “Yes, we say it’s beautiful, but just think of everything that lies behind it all, you know?”

“True, true.”

Unanimity. Which the chief engineer took advantage of to turn the conversation to the jet stream, the great band of wind racing through the topmost layer of the troposphere. Six to eight miles up it sweeps across continents and is capable of compressing the atmosphere into a single area of unbroken low pressure, or pumping it into an area of high pressure, just like a balloon.

“Picture it like a gigantic bicycle pump.”

She did, but meanwhile kept peering at the horizon: for some time now they had been sailing parallel to dikes on which occasionally a little building was to be seen, and even a church steeple poking up here and there. On one of these she spotted a wildly fluttering flag. That’s already the second or third today, she thought, until it dawned on her that it was Princess Beatrix’s birthday. How old was she? Fourteen? Fifteen?

“And finally we get to the weather,” said the chief engineer. “Rain, wind, yeah. Weather is never-ending, isn’t it? Strictly speaking, weather and wind are the backdrop to our entire lives.”

“Odd thought.”

“Air, that does nothing but stream from an area of high pressure into an area of low pressure.”

She smiled at him over her shoulder almost companionably, but he curbed this immediately. In a tone that was suddenly almost authoritarian he said, “Umm, as you will feel, the force of the wind is picking up by the minute!”

Meantime the ship had clearly changed course, and was beginning to pitch and toss. She noticed that the shorelines in either direction were farther away again and that they were sailing straight into the wind. The voice of the chief engineer, almost impossible to understand now, was still delivering his fantastical nature lecture at her. When she didn’t react, he tapped her on the arm.

“And do you want to know about this racket? Believe me, if the monstrous eye of this storm is gathering itself over the North Sea and sucking everything up with all its force — do you get it? — that’s what it’ll take — that’s when we can look forward to a really major show.”

This seemed to end the conversation. Seemed to, for Lidy, who was actually thinking, God, fine, now how can I just get rid of this man, stood for several seconds staring back at him.

“Yes?” asked the chief engineer.

She shook her head and looked away.

As far as the eye could see, the oncoming flood tide. Both of them looked at it, until the chief engineer turned to her again. Emphatically, as if imparting a conclusion, he said, “Vlissingen. Hook of Holland.”

Yes?

Could she imagine that after a weekend like this he was going to be really dying to know what the monitoring stations over there were going to produce as today’s measurements?

Feeble laugh. Her back half turned to him, she didn’t say anything in reply. The chief engineer moved so that he was in front of her again. She clasped her hands, rubbed them, and blew on them. Now what?

“I think I’m going to lie down.”

If that was okay with her. He said he was going to stretch out on one of the benches in the passenger area, the wedding he was coming from in Hoeksche Waard had gone on till dawn. There was nothing he liked better, he explained, than to sleep in storms and bad weather. So he was going to give himself a little foretaste of tonight. Hadn’t she had enough of the cold and the wind? Okay, he shook her hand and then in the same gesture threw his arm wide.

“Over there is England, that way at an angle is France, up there are the West Frisian Islands, and we’re in the middle. Imagine a sculpture made of water, an ocean mountain range, relatively low at the outlying foothills but rising to a monumental height in the middle, and then draw a vertical line from there to here!”

The chief engineer laughed as he headed for the stairs. His voice and the wind had been piercing in her ears.

Dusk. An afternoon in January. Lidy, on a ferry on the Krammer, knew roughly where she was. The Krammer is the southeastern part of the Grevelingen, and the Grevelingen is the arm of the North Sea that divides South Holland and Zeeland.

Known facts that could put up no fight whatever against what was playing out before her eyes, and not only before her eyes. Underneath her, in the depths, and behind her something was also in motion that could not be marked on a map or a chart. It did not even reveal itself to the eye. Huge and deafening, it seemed to survey its own surroundings, with intentions that no human being could put into words, for the simple reason that no human being had even the smallest role to play in what was going on. You could at best try to transcribe it as: a cold wind is blowing in off the sea — and leave it at that.

Читать дальше