Eventually she found the car keys on the desk in the consulting room.

A few minutes later Lidy, in a black Citroën, left the district where she had been born and raised and drove down the Ceintuurbaan toward the Amstel. At first, unfamiliar with the car, she had to grope for the gearbox. She practiced giving it gas a few times, used the engine to brake, gave it gas again. There was the crossroads, with the dilapidated church on the corner, then turn right. This was all part of a concatenation of different circumstances that had been set in motion the previous Monday, the 26th, when Armanda, in the grip of one of her spontaneous whims, had called Lidy to make her a proposal.

At first Lidy had hesitated. Staring at her fingernails, she had said, “Well, I don’t really know …” to which Armanda pointed out that such an unexpected and comical excursion could really be fun. At that point there was silence for a moment as both of them recognized that the answer, given their relationship, was going to be yes. The younger could talk the elder so convincingly into something that what began as a tiny glimmer soon became an idea and the idea in turn became a wonderful idea.

“You can have Father’s car, I’ve already wangled it for you,” Armanda coaxed Lidy, who was always ready to be persuaded, and already seeing in her mind’s eye a map of the western Netherlands stretching to the great arms of the sea.

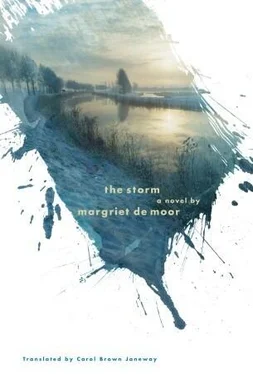

It had happened late at night. Lidy had gone to bed, but stayed awake until she heard her husband come home. He had undressed in the bedroom without turning on the light and immediately tucked himself in close beside her as he always did. Peace reigned all around them. There were no noises of traffic out on the street, and the trees in the park at the front of the house stood there as if they had never strained in a north or southwest wind. Nevertheless, at this very moment, thousands of miles away, a depression had been set in motion, a tiny area of low pressure. Forming above the Labrador Sea, it had moved quite rapidly in an easterly direction, picking up one or two other depressions as it advanced.

When Lidy took the highway toward The Hague, she was able to turn off the windshield wipers after fifteen minutes; it was dry. Nevertheless she felt herself being buffeted insanely. The wind, which during the night had torn across Scotland with hurricane force, uprooting entire forests, and cleared the east coast of England at around dawn, was for her no more than a constant pressure that forced her to keep steering against it slightly, to the right. It was something you got used to after five minutes and then didn’t think about again.

Shortly before she reached Maasshuis she stopped for gas. A young man in blue overalls filled her tank and washed her windows. Lidy followed him into the little office, which smelled of coffee and cigarettes. The news had just started on the radio.

“How do I get to the ferry?” she asked as the young man was closing the drawer of the cash register.

He indicated with his head for her to follow him and stood in the doorway to point the way. While Lidy nodded and took in the road that ran straight as a die until it finally curved slightly as it met a crossroads, the news announcer in the background began to read an announcement from the Flood Warning Service in a voice that projected no greater or lesser urgency than usual.

“… Very high water levels in the area of Rotterdam, Williamstad, Bergen op Zoom, and Gorinchem …”

Lidy thanked the man and stepped back out into the wind.

“You can’t miss it!” the gas station guy called after her.

And indeed she found her way quite easily. In no time at all she was at the harbor. She shielded her eyes with one hand. The water was very narrow. Nonetheless the far bank really was another bank, a gray line that seemed closer to being rubbed out than to holding firm. Her scarf tied round her head, she went to the pier, where there was a board with the ferry schedule on it. She read that the ferry coming from the other side wouldn’t dock for another half hour. There was a little hut, up a couple of steps, where she ordered coffee. Dim light, the radio again, she let herself slide into the general mood of passive waiting. Just sitting there, nothing more. Dozily she put a cigarette between her lips.

What am I doing here, for heaven’s sake? Who or what brought me here?

A quarter of an hour after she’d seen her sister alive for the last time, Armanda was walking across the market. She was pushing a stroller with a clear hood, and under the hood was Nadja. Because she was going to a party this evening, Armanda wanted to find a comb to wear in her hair. Because it was so windy and indeed the wind was picking up, many of the market people were packing up their goods and rolling up the awnings of their stalls. The pieces of cloth flapping around the poles contrasted with the anxious faces of the customers still peering inward in their winter coats gave Armanda the impression of a wild contagious abandon. She bought a comb and then added a couple of elastic hairbands decorated with tiny pearls. She pushed back the hood of the stroller and while the Syrian stallholder squatted down and held a mirror in front of the child, Armanda made two little ponytails on top of Nadja’s head and wound the hairbands around them so that they stood straight up; Nadja now looked like a little marmoset.

“Look how pretty you are….”

She loved the child. Nadja was something miraculous, the impudent trick Lidy had stunned her by pulling roughly two and a half years ago. Naked, in the room with the balcony, Lidy had poked herself gently in the belly with her forefinger. Armanda could still call up this image whenever she chose: tall, white Lidy, meeting her eyes in the mirror as she recounted how she’d been to the family doctor that afternoon, where she’d had to spread her knees embarrassingly wide over a pair of wretchedly hard stirrups.

“Oh, but …” Armanda had stammered after a pause. And then, “Didn’t you take precautions?”

Overcome by a strange, dejected feeling that she’d lost something forever, she had looked at Lidy in the mirror, as Lidy turned toward her with a motion that for Armanda was synonymous with hips, shoulders, soft upper arms, breasts: a woman far gone in a love affair. It had been the beginning of summer, the middle of May, and just as Armanda was working out that it must have happened at the beginning of March, the phone rang. She ran out into the hall. After the spacious brightness of the room, it was suddenly dark, like a tunnel. Suddenly uncertain, she stopped, facing the wall with the ringing telephone, then reached for the receiver and heard the voice of someone she knew well and consequently could immediately see right there in front of her but now suddenly as if for the first time: long-limbed, good-looking, blond, a strong face with a fascinatingly intelligent nose. I always liked to talk politics, money, and English literature with him, I always liked it when he kissed me in that seductive, dangerous way you see in French films, God, it was fine with me back then: he kissed my throat, made a funny snorting noise as he pounced on the nape of my neck, he breathed into my ears, and after he’d done all that, he looked into my face, and I saw that his eyes were terribly serious. Good. But when nothing happened in the days that followed, no letter, no phone call, nothing … why didn’t I wonder about it for a single moment?

It was Sjoerd Blaauw, a friend of hers who was now going out with Lidy. Still completely shaken, she greeted him with the first words that came into her head: “Sjoerd, while I’ve got you on the line, maybe you can tell me …”

Before she was able to ask whether the new Buñuel movie had opened at the Rialto, Lidy, in an unbuttoned checked dress, had snatched the receiver from her hands. There was a lot of breathless whispering, but Armanda was already out on the balcony, looking at the rear of the house on the Govert Flinkstraat, and it was dawning, dawning on her, as dawn it must, that she was already nineteen. A part of life she’d now missed out on, she thought. A shame, but don’t keep looking at it, that part has turned elsewhere.

Читать дальше