Thus it was that everything she still experienced was accompanied by the texts and nourished by them, as they echoed and reechoed in her head. “Take up Thy shield and Thy weapons …” Defiantly, shrilly sung verses that in no way decreased the howling of the wind, God knows, but acted as a commentary on it. A projectile slammed into her leg, she flinched in shock, but it didn’t really hurt. Once she got a brief but absolutely clear look at the overpowered landscape around her, the dikes heaved this way and that, the remains of farmhouses from which loud cries for help still came here and there. Then she had to reach wildly for whatever was at hand.

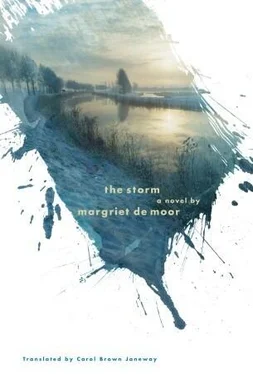

She was there. A kind of waterfall was pulling the door downward, but miracle of miracles, she didn’t fall underneath. The breach in the dike at Ouwerkerk was so huge that it could no longer be called a breach, there was simply no dike left. Half past six. The flood tide was still high, and the storm was still relentlessly driving the water from the north. Lidy lay half on her left side, her face on one arm, her legs spread, her feet turned to the side. Her little boat, with neither engine nor oars, obeying the current and the wind, was on direct course for the Oosterschelde, which leads straight into the North Sea. She was trembling uncontrollably, long past the point now where she could ask herself who she was, but still saying softly in her heart: “Here. I’m here!”

It was one of those suddenly very cold December mornings that transport a country into a state of excitement, disbelief, good feelings. The weather reports for the beginning of the week had used words like “dry,” “overcast,” “mild,” and had spoken of a moderate wind out of the southeast. The idea that the day begins with frozen water pipes and ice blooming on the windows of your car, which refuses to start, is therefore pretty far-fetched. Nadja and Armanda were in the train going from Amsterdam to Goes by way of Rotterdam and Bergen op Zoom. The rush hour was over, and the carriage wasn’t that full. They sat in facing window seats, looking out at the patches of white and the quiet sky, an optical phenomenon that struck them both as having a remarkable affinity with the purpose of their journey. A funeral, but not of anything that could be understood as a dead person or even a dead body. After more than thirty years in silt, what remains of a human body is little more than some bones, two jaws, a skull. Armanda and Nadja stared out at the thin, fresh layer of snow, the result of a trough of pressure that had moved southward over the North Sea during the night, and let their conversation lapse for a while. Since Monday of the previous week they had known that Lidy — maybe — had been found.

Their shocking return to her trail, long abandoned, totally lost, had begun a month before. On the aforementioned Monday afternoon, Armanda had received a call from a representative of the local police, who asked her if he was speaking to Mrs. Brouwer. Within the hour a man in street clothes, with soft gray eyes and a sailor’s beard, was sitting at her table. He informed her, wanted at least to give her the information, that they had first gone looking for Mr. Blaauw, then for the Brouwer family, who had once lived on Sarphati Park, but then quickly switched to the question that was burning in her eyes. Lidy Blaauw-Brouwer. Indeed. You would like me to tell you where?

A short silence. Another glance. In the mud near the Schelphoek, the construction site behind the secondary dike on the northwest bank of the Oosterschelde, right near where one of the three great river channels, the Hammen, drains into the estuary and where they’ve been building the gigantic flood barriers for years now—

She interrupted him. “How …”

He waited while she bent down to scratch a bone in her foot, then stared up at him, motionless.

“How is that possible?”

“You’re right,” he’d replied. “On the face of it, it’s impossible.” He seemed to be searching for the facts. “Totally impossible, so I’ve heard.”

She leaned over the edge of the table, as if taking a first step toward this barely credible possibility, and waited. A backhoe was the first detail that she could get hold of, and then she had a mental image of the practical little Bobcat which a skilled operator can maneuver with real speed and agility. It had been in the middle of the previous month, one afternoon around five. But isn’t it dark by then? It had been getting dark. And the skull that had been dug up had been stained very dark by the earth it had been in, all that silt and heavy clay and peat, too.

Her sister, if indeed it was her sister, must …

She made a gesture. A moment please.

“At five o’clock there’s nobody still working on a building site, surely?”

The plainclothes policeman had looked at her thoughtfully, brought up short by her question, then he’d gone back to talking about the back hoe operator. Who had summoned a coworker still running around on the mudflats, the eerie area at the mouth of the Oosterschelde, dug up and dug over for years now as they tried first one method, then another, to effectively block the arm of the sea. They used scoops to collect a few skeletal fragments, which they laid out together in the open air. Their workday was over, but they managed to find a construction foreman still in a trailer with a telephone. Shortly before total darkness fell, the national police came and put all the parts in a plastic sack and took them away, including a small, eroded piece of metal, some kind of hinge or spiral, possibly a clue, which had evidently, as was visible in the flashlit photo, been lying there too.

Yes. Exactly. Pause. Mutual appraisal. Then Armanda watched as the policeman removed a piece of paper from the little portfolio he had set down on the table as soon as he arrived. He unfolded it and pushed it between them in such a way that both of them could have read it if they so chose. The attorney general, Armanda understood, twisting her head sideways to stare at the sheet, which appeared to be a form letter, a typed report or some such, had given his authorization for the transportation of the body parts. Authorization, aha. Her eyes fixed on the paragraphs of type, she withdrew herself somewhat from a situation that on the one hand spoke of an end to a great and apparently insoluble riddle — whatever confusion might accompany it — and, on the other, phrases like “the judicial laboratory in Rijswijk, that usually requested Leiden’s help in the business of attempting to make reliable identifications.” She didn’t look up again till her visitor said something that seemed to connect with the known world.

“Your sister, if it is indeed your sister, must have been buried in a layer of mud very quickly after she was washed ashore.”

“Yes?”

Then came explanations to clarify that not one single person missing from 1953 had been found in the last ten, no, twenty years. “It’s a real miracle, lady,” hard to imagine just how fast a body disintegrates in water, particularly seawater, till there’s absolute nothing left. “Five, six months at the most,” depending on the factors involved. Armanda, who was maintaining an air of great interest but couldn’t keep up with the dizzying speed with which thirty years were reduced to zero in a single blow, heard phrases like “low or high water temperatures,” “polluted water,” “crabs and crayfish,” and “ships’ propellers.” There was no doubt that it was thanks to the mud and its capacity for preservation that so much of “your sister, possibly” had survived.

But not enough.

“Can you give me a photo of her to take with me?”

The policeman asked this after he had made a dome of his fingers before setting his hand down over the paper on the desk. Based entirely on the long bones and the pelvis, the hand went on, Leiden had decided that what was involved here was a female, twenty to twenty-five years old, height approximately five foot ten, probable date of death, 1953, since the cartilage had stopped thickening. Armanda was on her feet. Yes, just a moment, please … yes, a photo! A photo they could lay on those dark, cold long bones and that pelvis that are such good indicators of probable age! And wasn’t it high time she should offer her guest a cup of tea?

Читать дальше