That left the real end of Father Brouwer.

If Jacob had been at home more often, Betsy and Armanda wondered, would he have seen that Father, who was now refusing medical supervision, was going downhill again despite how well he looked? Perhaps, but Jacob, the doctor without borders, as the family called him, had been sitting in some godforsaken corner of the world for almost a year, and barely made it to the funeral. Okay, Armanda said now, but shouldn’t she have seen it as a warning that in the last weeks he kept calling her Lidy?

She lowered her head in thought, and wondered, “As if the person he really wanted to remind was himself …”

“Dammit,” said Betsy, “he’d forgotten her, the first time he died.”

“Yes, as if in his heart she’d ceased to exist for him who knows how long ago. None of us noticed at the time. It was all so peaceful. I can remember thinking: How lovely to end your innings that way, so friendly, so nice, so serious. And a last heartfelt word for each of us. But yes, one name was explicitly left out….”

Armanda and Betsy looked sadly and quietly at the cups on the table in front of them. There had been nobody at the next one, at deathbed number two. So it was inevitable that everyone would start imagining all sorts of things, whether they were applicable or not.

And it hadn’t been a deathbed but a half-worn-out Bukhara rug on a herringbone parquet floor. Jan Brouwer was lying next to his desk, in the undisturbed consulting room on the first floor, when his wife found him, after calling and searching, at around four o’clock on the twentieth of October, 1980. The light in his eyes was already gone, but because of the bizarre course of events in the last year, she couldn’t believe it without further checking. She telephoned Doctor Goudriaan at once, couldn’t reach him, and called Armanda. Armanda had knelt down and was looking at the worried expression on her father’s face, with its eyes still open, making him look as if he were objecting to something, when the doctor on call came into the room. His rapid examination was no more than a ritual, an answer for wife and daughter.

“God, we were in such a state,” said Armanda. “I remember the two of us kept asking in unison: So? What do you think? Shouldn’t you call an ambulance? Shouldn’t we lift him onto the sofa? Couldn’t you do CPR right now?”

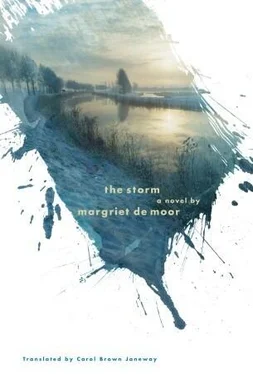

29. Out on the Oosterschelde

The mat of reeds sailed on. Hocke lay pressed tight against her back and hips. He had wrapped his left arm over her body and stretched his right arm next to hers and up over her head. She had let go of the stalks to twine her fingers into his. Lovers lie like that. The heavy black sleeve of her coat was pushed up a bit. The storm raged on unchanged, with wind gusts of seventy-five miles an hour over the water; it was simply shifting a little from northwest to northeast. The moon had reappeared with a bluish cast that negates all sense of depth and volume and gives everything a particular visibility, so that space itself acquires a perspective all its own, in defiance of all normally accepted theories. Lidy’s wrist, as bony as a child’s, trailed in a witch’s cauldron of sheer brute force. She had forgotten what a house is, or a marriage, or a family — that kind of thing is quick to go.

Lying in a reed bed engenders a sense of earth, of land, even despite the wetness. But this part of the landscape was moving, and moving with some speed, in a southeasterly direction, which didn’t mean much to Lidy anymore, as she had lost all idea of land. For the space in which she found herself alive, depleted and exhausted, but nonetheless alive, was an enormous unknown. The whole system — focal point, outlines, verticals — was heaving and surging in the uproar. Moon, clouds, and stars, which she had always believed belonged in the firmament, came up at strange angles out of what had become a wild waterscape to right or left. Yet her heart beat on, without anything she could have described as a fear of death. Her fingers held tight to Hocke’s. She had not forgotten what it is to want to live.

An hour passed in this fashion. Dusk. From time to time another squall of snow. About three feet away from her, another figure was lying in the flattened reeds. Gerarda Hocke. Lidy wasn’t clear, nor was she even wondering, if the old woman was still among the living.

The hunchbacked boy had been gone from them for quite a while now. When they lost him, it had been pitch dark. The section of floorboards they had been sitting on found itself above the dead-end street of Paardeweg near Nieuwekerl, a village in the process at that very moment of crumbling street by street. The floor planks went shooting over a flooded network of ditches, eddies, and little bridges, which together were causing an angular momentum, not that powerful in and of itself but wide-reaching. The shaking of the raft doubled and redoubled, because there was no letup. Visibility was almost zero. Yet as Cornelius Jaeger rolled off the raft, Lidy saw it, and saw for the first time that the child was in fear. Eyes are fine lenses, they don’t just capture light, they also emit it. As the boy lost his grip on the planks, he sent up a wordless plea for help with every ounce of will left in him. Lidy saw a pair of shiny green eyes, little facets, flat not curved, that contained nothing in the world that could be described as a look or an expression, just simply a signal that read Mayday, help … and indeed she literally flung herself forward.

Save him? Her? Action? To weigh this in a fraction of a second, in the belief that she was responsible for the suffering of the little hunchback? Not a moment later, she herself was thrown from the saddle.

Half water, half land. A hybrid of coastal vegetation that came from a bay on the north side of the polder of Sirjansland, part of which bordered the Grevelingen. The mat of reeds had already come an unimaginably long way. Lifted up and then helpfully supported by the flood, this mere line in the air had traveled ten miles to give three drowning people, Hocke, his mother, and Lidy, the feeling that they were crawling onto land. There is no need to remind anyone half drowned what that is. Land means territory, something in principle you can stretch out on. Even when it is saturated with sea and river water and the ever-thinning layer of silt. Formed by the North Sea, really no longer being held together by the roots underneath, you can drag yourself onto it, using your knees to work your way up, and feel you have reached dry ground. The old woman was more or less thrown onto it by a wave. Hocke and Lidy had to search for each other amid the floating wreckage of the storm, clutching then losing each other again among the cartons, branches, chests, sacks of potatoes, clothes, corpses, and bottles and finally just hoping for the best. The false island of reeds was still roughly seven feet by ten as it continued its journey. Lidy, very sleepy now, closed her eyes. The wind roared in her eardrums, the snow tasted of salt. Barely conscious, she knew that she and Hocke, wrapped in thick wet layers of fabric, made a single body. God, they were saved!

That had been an hour ago. But what is an hour when one is humbly embarked on the road to infinity? From now on, time, an element that is supposed to “pass,” would be absolutely worthless to both of them. A pair of lovers. Enclosed by sky and sea. Two beautiful people, in fact. Each potentially widowed from the first moment they met. As a boy, Izak Hocke had always assumed that when the time came he would marry his great love. Thereafter he remained a bachelor for years. Was there such a girl anywhere? Lidy, on the other hand, had been madly in love two or three times, when her impatience — and, naturally, her ovulation — made a decision one day at the end of February 1950. What are they doing here, body against body? Lidy, a tall white child of the city underneath her dark clothes, and Hocke, a farmer?

Читать дальше