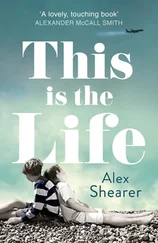

Yours ,

Michael Donovan

I stood there for a moment. He had not even realized who Mr Jones was.

Then, slowly, I made a space at the kitchen table and looked at Donovan’s piece: Some Problems of Supranational Law.

It read, needless to say, like a dream. Donovan explained how he had attempted to construct a jurisprudence of supranational law and how and why he had failed. He listed the obstacles he had encountered (more, many more than I had envisaged) and said that, as international law was adapting quickly to the new circumstances — he cited the Montreal protocol as an example — there was no need to develop supranational principles. He had fallen into the monist trap, he said. He concluded that the way forward was to describe and elucidate the developing rules of international co-operation rather than to seek to formulate a prescriptive, ideological jurisprudence.

I dropped both pieces, his and mine, into one of the bulging plastic bags that surrounded the dustbin. I gave a dry laugh. So much for Donovan as the new Grotius. So much for Donovan burning his book for love. So much for Donovan as the instrument of my downfall.

So much for all of it. Sitting there in the buzzing, reeking kitchen, I saw, for the first time, what had happened. Nothing had happened. The whole thing had come to nothing.

I began to feel unwell again, again it seemed as if the floor was tilting like a deck at sea, and I had to close my eyes and wait for the room to even out. When I opened my eyes I was sweating. Feeling panicky, I thought: the Donovan story, with all of its twists and mysteries, came down to this: he was a busy lawyer who had been through a difficult patch with his wife and who had tried unsuccessfully to write a difficult book. That was it. There it was, the long and short of it. As for me, my story was nothing special, either. It was not even the story of a hard case, a poignant tale of might-have-been, of a man unluckily deprived of his vocation and true self. No. I was simply a solicitor who, in the last year, had badly deluded himself. No more, no less. I had not been in any adventure, in any real-life thriller. When I had seen history and destiny and tragedy and love story in what had happened, I had been seeing things. There was no special link between Donovan and me, nothing other than the usual, flukey contiguities. My road was not a tributary of his road.

Then I took a grip of myself: Donovan’s story? My story? What was I thinking about? People do not have stories, they have lives; they have a spell of sticking around in the flesh, and then they are no more: that is what people have. And I thought, Roads? Roads? Roads have destinations, roads take you to places, that is why we build them. But Donovan and I — we were not going anywhere. Even if Donovan published his book, even if he became the greatest jurist since Hugo Grotius, even if he lived happily with Arabella for the rest of his days — where would that get him? And even if I was sucked into his historical slipstream, even if every one of my dreams came true — where would that leave me? Dreams? You dreamed when you were asleep, or at the movies. Wake up, Jones, I told myself. You’re not in some film here, this is the real thing. This is not Disneyland, this is Earth, a planet in an unremarkable galaxy in the suburbs of a universe in the middle of nowhere. No one was going anywhere. No one, not even Donovan, had anywhere to go.

I went to bed. I lay curled up there for the rest of the day and, the next morning, I stayed put. There was nothing to get up for. It was not that all the doors of my life had slammed shut, it was that there were no doors. I lay there feeling terrible, thinking, My future — where was my future? I pictured the forthcoming events, the passage of the calendar days, and no matter what I saw — myself at Batstone Buckley Williams or, if they threw me out, myself elsewhere, working away for years to come — I saw no future. Even if I envisaged myself as a heroic international lawyer I could see no future.

I thought of Susan, I thought of how she worried about just this point. Right then, I could have done with Susan next to me to warm me up. I could have done with her arms around me right then.

Eventually — how or why I do not know — I got out of bed. I felt heavy all over again, like an astronaut kitted out on Earth. But somehow I got around to cleaning up the house. I worked solidly for three hours. I scrubbed the kitchen, killed the flies and rejuvenated the living-room. I moved the dust and polished the silver and disinfected the sink. I took the rugs into the garden and beat great puffs of dirt out of them. For one reason or another, I just kept plugging away. I washed and shaved and walked slowly to the tube station and took the train up to the office. I felt empty as well as heavy, I felt scooped out.

I got into work and sat behind my desk. My job was on the line, but I was not afraid. I did not care, to tell the truth. It did not matter to me what happened. Then, after a while, I went to the senior partner’s office and knocked.

‘Ah, Jones.’ The old fellow gestured towards the chair.

I sat down.

‘Feeling better now, Jones?’

‘Yes, thank you,’ I said.

‘It must have been a terrible shock for you, losing your brother like that. A terrible shock.’

I said nothing.

Old Boag looked me in the eye. ‘Well, feel free to start whenever you wish,’ he said. ‘My condolences, and the firm’s.’

‘Thank you,’ I said. ‘I’m sorry I haven’t …’

I did not finish my sentence. Old Boag was waving his hands. Forget it, he was telling me. Don’t worry about it.

I went back to my office and looked down on the clattering street for a time. Everyone was rushing to and fro and up and down as though nothing was the matter. They were scurrying over zebra crossings, leaping off buses, honking their horns, pointing at displays and raising their voices. A wind blew through the street and everything fluttered and then went back to normal again.

I heard a thump behind me. It was June, June with her fire-engine smile. She had brought me a steaming cup of hot tea.

‘Drink it,’ she said. ‘Come on, it’ll do you good.’

I picked it up and took a weak gulp. ‘Thank you, June,’ I said. ‘That’s delicious.’

She watched me drink. ‘If you need anything — anything — just ask. All right?’

Off she went, trotting back to her desk. June.

I picked up the telephone receiver — it weighed like a bar of lead — and made a couple of calls. First I rang my brother Charlie and told him what the score was. Then I rang Susan’s office. No, she’s not here, they said. I should have known better, but I felt a flicker of hope for her. I said, You mean, she no longer works there? She’s found another job? No, they said. She’s out for the moment, that’s all. I wanted to leave Susan a message of some sort, and I searched around in my mind for something to say. I said, Say James Jones rang.

What now? I thought. Where to next?

I had to keep busy. I picked up the telephone again and dialled Lexden-Page.

‘I’m terribly sorry, Mr Lexden-Page,’ I said.

‘That’s all right,’ Lexden-Page said unconvincingly. ‘I heard you were going through a patch of trouble. I’m sorry about your brother, Jones.’

I said tiredly, ‘Well, what are we going to do about your case, Mr Lexden-Page?’

Lexden-Page found his old tone. ‘We’ll fight it, Jones,’ he said excitedly. ‘I’m not taking this lying down.’

Poor old Lexden-Page, he did not have a hope in hell. Not only had his appeal to the county court failed, he had also been refused leave to appeal. He would have to get leave to appeal from the Court of Appeal (impossible) and, on top of that, win the actual appeal: also impossible. Even then, if he wished to continue fighting, he would be refused leave to appeal to the House of Lords, who in any event were bound to dismiss the appeal proper. The whole thing was impossible, an utter non-starter. Lexden-Page was going nowhere, and it was time that he got this into his head. It was time that he woke up, faced some facts.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу