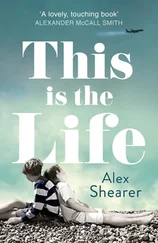

I pulled out another cigarette. So this is what had been happening all along. This is what had been significant about the Donovan story — not international law, not history, not me, love.

I recognized that this final version did me no favours. I preferred the original scenario, with me as a player, as a footnote in the history books. Now, it transpired, I was a minor, dispensable character, with no part in the final, crucial reel, where the Donovan drama had come to a climax, where Donovan had somehow saved his marriage. My story — a hard-luck story — was by-the-by. In the end, in the final cut, I had been edited out.

I did not mind. This was the wonderful thing. I was not bitter about the outcome. I looked on the bright side: it had been an adventure. That was what was important, that was what I took away from it: for a few months, I had lived vividly; for a few months, my obscure little life had been lit up.

I looked around at the debris everywhere and rubbed my hands and rolled up my sleeves. The Donovan story had ended. The lights had come on and it was time to put away the popcorn and head for the foyer. Time to clear up this mess and get on with my life. I went into the kitchen and fetched a bin-liner and began filling it with clinking, smelling objects. Then, when I had loaded up the bag and knotted up its mouth, I ran into a problem: I ran out of bags.

Two minutes later I passed out in bed. Too tired to go out to buy more bin-liners, I had undone the full one and had tried cramming it with more stuff. It had not worked. All that had happened was that the bag had ripped open along the side and some sour, coagulated milk had dribbled out on to the floor. It was too much to face. I had been through enough that day. There was always tomorrow.

The next day I hoisted my dripping body out of the tub and got ready to face the world. I shaved and washed and knotted a tie around my neck. Then I caught the tube up to the north bank of the river and wandered down the sunny Embankment gardens to the Wig and Pen, a drinking club on the Strand. I am not a member there but, as my face rings a bell, I am taken for one. Over the years I have come to befriend some of the boys who go in there in the afternoon, and on this occasion I was optimistic about running into someone I could talk to. By the time I stepped into the bar I was in a nice, uncomplicated state of mind, looking forward to my first normal conversation for weeks.

There was hardly anyone around. Two barristers were huddled in a corner and an old red-faced fellow was reading a newspaper at the bar. I took my glass of wine and sat a few chairs away from him. One hour and several drinks passed and, although the place had started to fill up, no one had spoken to me. Then joyfully, I recognized a face.

‘Barman, two bloody marys!’ I cried.

Oliver Owen regarded me. ‘Well, I must say, you’re looking more, shall we say, more substantial than the last time we met.’ He pointed at the shirt stretched tightly over my stomach. ‘What are you hiding in there, a basketball?’

‘Do not mock me, sir,’ I said flamboyantly, handing him his drink.

‘Correct me if I’m wrong,’ Oliver said, but the last glimpse I had of you was of your fleeing rump en route for your office bog. Not an attractive spectacle, if you’ll permit me to say so.’

‘You refer to that ornament of the social calendar, the Batstone Christmas party,’ I said. ‘I remember the moment well. You had just dropped your bombshell when the drink suddenly got the better of me and I was forced to take flight. Most embarrassing.’

Oliver wore the look of amusement he invariably wears in my company. He stands up straight and looks down at me with a sly, discriminating smile. ‘What bombshell? You’re not talking about my female pupil, are you? What was her name?’

‘Diana Martin,’ I said. ‘No, I use “bombshell” not in the sense of a knockout beauty, but in the sense of an item of devastating news.’ He kept looking at me, forcing me to elaborate in a casual, jolly tone. ‘Remember. You told me how 6 Essex tried to get hold of me to offer me a tenancy when Tetlow had gone, but couldn’t find me? Well,’ I said, ‘that came as a bit of a surprise. Hence my use of the word “bombshell”. Comprendo?’

Oliver frowned with a smile on his lips. ‘Did I say that?’ Then he looked at me and started laughing. ‘You didn’t actually believe me, did you?’

I said, with will-power, ‘No, no, of course not. Of course I didn’t. Don’t be ridiculous,’ I said.

Oliver kept laughing. He tossed his head back and just went on laughing. ‘You did believe me, didn’t you? You thought that we’d turned the Temple upside-down looking for you, didn’t you?’

I said nothing. I tried to come up with a smile and voice a denial, but I could not. The muscles around my mouth had collapsed.

‘Don’t get angry with me, James, it sounds like I was doing you a favour.’ Oliver was still laughing. ‘You wouldn’t want my pupil to think that you’d failed to get into chambers, would you?’

There was a silence as Oliver swallowed his chortles and straightened his face. Then he spluttered into his glass and began laughing again.

I finished my drink. ‘I’ve got to go,’ I said, knocking my stool to the ground.

I lurched through the door and, stunned by the sunlight, reeled for a moment on the pavement. Then I waved down a passing cab, fell into the back and nodded off, my head rolling around on my chest as we took the corners.

I awoke in my living-room at half-past seven (it strikes me, looking back on these last days, just how much sleeping and waking I did). I had a go at standing up. I felt sick. Close your eyes, pirouette a few times and then open your eyes: that was how I felt. Events had whipped me around at such velocities and from such acute, unexpected angles, that I was turning like a top.

When the spinning passed, I went into a daze. There is only so much shock and setback and realignment a man can take in a day. I stared at the television for a while and fell asleep on the sofa.

Nothing had changed in the morning. Everything was still the same, the flies, the drizzling dust, the mess. So this was it. This was my new, post-Donovan world. This was my life. A house filled with trash, a dead-end, soon-to-end job, and at their centre, me, James Jones. James Jones, I thought. James bloody Jones. Solicitor, bachelor, small-timer, loner. He had me trapped, the bastard. He had me locked up. I felt like that unfortunate fellow in the story, the one who woke up one morning to find himself imprisoned in the carapace of an enormous, despicable insect. Jesus Christ, I thought with a sudden, lucid horror, I was stuck with him — I was stuck inside that fat, failed, unloved bastard.

In pain, I rolled off the sofa and started walking around the house to empty out my mind. Like a zombie I just wandered around for a few minutes, trying not to think. Then I saw that I had received a thick envelope in the mail, and that it was from the International Lawyer. I remembered: the article I had sent them early in the year, when I had revived my studies. They had finally got around to returning it to me. What a joke, I thought. To think that I imagined that the learned editors of that journal would ever consider an article by a nobody like me. To think that I imagined that I could ever grasp, let alone master, the problems of supranational law — and in two weeks. (And yet, when I fingered the letter, I was pounding …)

I ripped open the envelope.

Dear Mr Jones ,

Thank you for your paper on the problems of developing a supranational law. I read it with great interest. Unfortunately, the International Lawyer already has a piece on this very subject, written, I am afraid to say, by myself (I have enclosed it for your interest).

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу