“I wish I had taken you back to the room that evening,” I stirred with desire. “I wouldn’t have said that I had missed the crossed treble by a whisker.”

“I wish you had too. You don’t think I’m too old for you?” there seemed to be tears on her face.

“No. It has nothing to do with it.”

We played, cumbersomely: and yet, when her breathing grew heavy, and my fingers smeared the rich oil along the lips above the half-shattered hymen, I, sure in the knowledge that she could hardly turn back from her pleasure, might be a poor Colonel Grimshaw, and she, excited and awkward by my side, might be his Mavis.

When I heard her catch towards her pleasure I rose above her and she opened eagerly for me, guiding me within her. The Colonel should drive and shaft now and she be full of his thunder, but I lingered instead in the warmth, kissed her in case I would come and die.

We were man and we were woman. We were both the tree and the summer. There was no yearning toward nor falling away. We were one. It was as if we were, then, those four other people, now gone out of time, who had snatched the two of us into time. For a moment again we possessed their power and their glory anew, pushing out of mind all graveclothes. We had climbed to the crown of life, and this was all, all the world, and even as we surged towards it, it was already slipping further and further away from one’s grasp, and we were stranded again on our own bare lives.

“Six or seven hours ago we didn’t even know of one another’s existence,” she said.

“That’s right.”

“And you don’t think you love me even a little?”

“No. Love has nothing to do with it. How do you feel now?”

“I feel great. I don’t feel guilty at all or anything. Only I’m afraid I’m beginning to grow fond of you. Do you think you might grow fond of me?”

“I don’t know. I don’t think you can programme those things.”

“And, you’ve done this with several?”

“With a few,” I was growing irritated.

“Without loving them?”

“I loved one woman but love has nothing got to do with this. I don’t think it is important now. It was blind. That was all.”

“Who was she?”

“She doesn’t matter now. Some other time I’ll tell you.”

The coal fire had almost died, throwing up the last weak flickers. In a tear in the curtain I could see the grey light outside.

“Will your aunt and cousins not notice that you are out so late?”

“I’ll say that I was at a late-night party. I suppose though I should be making a move.”

“I think it’s close to morning. What I’ll do is walk you to a taxi. There’s no telephone to call from. And there’s always a car in the rank at the bottom of Malahide Road.”

“I don’t feel guilty or anything. I feel great. What is it but what’s natural,” she repeated as she dressed. “How do you feel?”

“I feel fine,” I said.

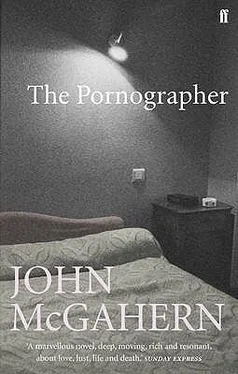

When she went out to the bathroom and I turned on the light the room seemed incredibly small and lonely and undamaged, like a country railway station in the first or last light.

“Are you ready?” I asked.

By way of answer she kissed me and we went out of the house in the early morning stillness. We walked in silence down the road empty except for a milkman and his boy delivering bottles from a float, the whine of the electric motor starting between the houses and the rattle of the bottles intensifying the silence.

“I suppose this is the usual. Now that it’s over it’s just goodbye,” she said as we drew towards the end of the road.

“No. I was hoping we’d meet again.”

“When?”

“What about next Wednesday?”

“What’ll you be doing before then?”

“I have some writing to do. And there’s this aunt of mine who’s in hospital who I have to go to see.”

“Where will we meet, then?”

“Do you know the Green Goose?” and when she nodded I said, “We’ll meet up in the lounge at eight o’clock.”

We kissed again as I held the door of the taxi open, the stale scents of the night mixed with fresh powder or perfume. I gave the taxi man the address and told him I wanted to pay him now. He looked cold and disgruntled in a great swaddling of an overcoat and counted out the pile of silver I gave him, only acknowledging it when he reached the tip. As the taxi turned in the empty road, the traffic lights on red, I saw her waving in the rear window in much the same exaggerated way as she had walked towards me at the head of the dancehall stairs.

After the sharp night air the room smelled of stale alcohol and perfume and sweat. I tried to open the window but it had been shut for too long and I was afraid the cord might break and wake people in the other rooms. I washed the glasses, bathed my face in the cold water, and when I drew back the crumpled pile of sweat-sodden clothes there were blood stains on the sheet. I shuddered involuntarily as the mind traced it back, and the grappling of the hours before stirred uneasily and did not seem to want to grow old.

I sipped at the coffee in the upstairs lounge of Kavanagh’s the next evening, the two Marietta biscuits on the rim of the saucer, unable to free myself from the unease of the haphazard night, and I concentrated on the barman wrapping the bottle of brandy I had to take to my aunt in the hospital, thinking energy is everything, for without energy there can be no anything, no love and no quality of love.

For long I had limped by without energy, accepting what I’d been given, taking what I could get — deprived of any idea outside the immediate need of the day. Once the sensual beat had carried me on, careless of reason. Now I wanted to pause and turn and pause and stare and pause and idiotically smile. Colonel Grimshaw mounts his Mavis Carmichael and her ever-ready juices grease his ever-seeking bayonet, both rapturous as they hold the ever-rising tide of the seed on the edge of spurting free. They are in Majorca now. Blood dries on woollen sheets in Dublin, salt and water unable to sponge it completely clear.

The barman searched for my eyes as he twisted the brown paper round the neck of the bottle and putting it on the counter called, “Now.”

“It could pass for Lourdes water,” I said as I counted out the money.

“Aye,” he laughed agreeably as he rang up the price and said apologetically as he handed me the change, “only it’s an awful lot dearer.”

“There’s nothing going down except ourselves.”

I walked the hundred yards to the taxi rank at the bottom of the road. Two taxi men were playing cards on the stone drinking trough, their cars waiting by the curb. When I gave the name of the hospital, one of the men motioned towards the first car but I stood—“There’s no rush”—to follow the short game to its close. When we pulled away into the green of the traffic lights I saw her face as she waved in the back of the turning cab of the night before, and wanted to turn away from it. Then I gripped the brandy bottle and sat back and listened to the ticking of the meter as the taxi took me like some privileged invalid through the fever of the city in its rush hour. When we turned in at the hospital gates, with its two white globes on the piers, the city gave way to trees and soft fields, and suddenly in the middle of the fields the concrete and glass block of the hospital rose like some rock to which we must crawl to die on when the blessed cover of these ordinary days is all stripped away.

I caught her sleeping lightly, some late sun on the pillows from the high windows facing home. Her hair had grown so thin that if I was to smooth her brow I felt the fingers would move back through the hair without disturbing the roots, and the last traces of gender seemed to have slipped completely away from the face. I touched the bedclothes above her feet and she was shocked to see me when she woke.

Читать дальше