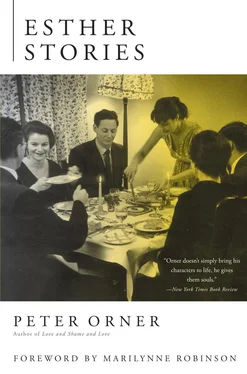

Peter Orner

Esther Stories

To my brother, Eric,

and

In memory of Andre Dubus

I have spoken of the origin, progress, and present condition of this new and thriving place. But notwithstanding these ever falling waters, and these granite buildings, and all this iron machinery, and everything that looks so strong and permanent around us, the time may come when this village shall be raised from its deepest foundations. Where are the people of former ages?

— Reverend Orin Fowler, History of Fall River, Massachusetts, 1841

These engrossing stories are too pure and subtle to be called a proof and demonstration of the power of literary realism. Such a statement would have to be translated into suppler language in order to sound as true as it is in fact — into words that could respect how naturally the stories are told, how quiet they are, how innocent of pretense and full of implication.

Realism has been so predominant a style among American writers for so many generations that it is easy to forget it is a style, and a sharp departure from the courtliness and conventionalism that had prevailed in earlier centuries. Its lineage is clearly traceable to the Enlightenment and Romanticism, when writers awakened to the poetry of common speech and the revelations of ordinary daylight. Over the years it has sometimes taken on a moralizing tone, often in association with sensationalism, that famous elixir of flagging invention. But in itself it is both impetus and method for exploration of the astounding world of human experience, the impetus being that the subject is inexhaustible, and the method being the resource of insight and intuition any writer can bring to it. Nothing prevents realism from being called a metaphysics of consciousness except an honorable realist dread of entrapment in categories and abstractions on one hand, and, on the other, a superficial familiarity that masks its most interesting effects.

Time is a subject in Esther Stories. This most universal and commonplace experience is also a great mystery, to science, to philosophy, to any reflecting mind. These fictions stir a kind of recognition that is as intimate as awakened memory, acquiescence in a knowledge so habitual we are startled to be reminded of it.

A boy and girl spend a furtive night together at an abandoned motel. Virgins before that night, they imagine themselves transformed by this shared initiation. They are eager to try the effects of the change on their school friends. But the boy wakes in the morning to find that the girl has left him there, driven off in his car. He is stung by this act of abandonment, his rage and bewilderment seemingly out of all proportion to the act itself. She has left as a kind of vengeance in anticipation of abandonment she knows she will suffer—“her father had gotten away with it.” And he knows the grief he feels will matter, that “this right now will always be worse than any funeral.” Their step into adulthood awakens the demons waiting there, memories that bring with them inevitable iterations of grief and dread and self-defeat. The past spreads into the future like the waters of a flood, its flows and currents dominating the landscape.

An old navy veteran has only one memory, a story he tells compulsively, not remembering that he has told it before. It is the memory of one atrocious act for which no confession or contrition is adequate, and it, with its rituals of attempted release, is more present to him than present time.

A woman whose presence has power that might be attributed to beauty or charm, but which is not to be accounted for in such conventional terms, is the pride and grief and fascination of her family and is isolated from them by this very fascination. And after her early death she lives on in their stories, mysterious as she ever was in life, immortal in her isolation.

Often the settings of these stories are those American places that are both provincial and universal, unheard-of towns with familiar customs and landmarks, like almost anywhere on the Fourth of July. The hauntingly recent past is abandoned along the highway, falling into unconsecrated ruin, speaking from the peripheries of awareness, having no appeal to make for itself except to the intimacy of colloquial memory. In this light, or twilight, the appeal is not to be resisted.

In Esther Stories events send their repercussions across time so that they become event again and again, like sound or shock. Their magnitude cannot be measured apart from their effects. These stories are tentative measures of impact as it moves through families or generations, or is felt by a stranger in the outskirts of a town where a murder happened, or in a house where a tenant has died. Unquantifiable in themselves since by implication their consequences have no certain limit, they come near erasing our hierarchies of relative significance. We know now what a telling spark can be struck from a pervading and invisible medium of reality. These stories make the same discovery.

Marilynne Robinson

Initials Etched on a Dining-Room Table, Lockeport, Nova Scotia

THE GIRL was young when she did it, and she didn’t live there. This was in 1962. She was eighteen. She’d been hired to tidy the place. It was three, maybe four years before anybody noticed. The letters were so small, and they always ate in the kitchen. And when they did discover them, she was already gone to Halifax. By that time the girl had a reputation to escape from. So when they put two and two together and figured out it was she that did it, they weren’t surprised. Of course she’d be the one to do something like this, they said — shameless girl, not shocking at all.

A cod fisherman, a captain, lived in the house with his wife, one of the original Locke mansions on Gurden Street overlooking the harbor. They never had children, but dust collects nonetheless in a house so huge. The girl had never been in a place that grand. At least that’s what they told each other when they found her letters. RGL. That she’d wanted to leave her mark in the world, something that would last, something that would stay. The family still lived in town, her father and brothers sold hardware, so they could have held somebody accountable for the damage if they’d wanted to. But the captain and his wife talked it over and decided not to mention it to anyone. Not that they approved — Lord no. It was defacement of property. Vandalism. Of course it was an heirloom; it had belonged to her mother’s mother, a burnished mahogany drop-leaf built in York in 1844. They could never approve. But they were quiet people; they kept to themselves in the hard times, and even in the good times they held their distance. Besides, what could anybody do about it now? What was done was done. Still, that didn’t mean the captain’s wife didn’t watch more carefully over the other girls who came to clean, and it didn’t mean the captain didn’t sometimes think of her sugar breath, that morning, the one out of a thousand when he was home and slept late — he’d startled her in the kitchen. Captain Adelbert! I didn’t have any idea you were home, me banging the pots down here to wake the dead. His only intention was to touch her sweater (Lucy was out, still teaching school then), but he couldn’t stop and kissed her, her hands at her sides. She didn’t resist or desire, and that had made him a fool for years.

Yet over the longer years — when the fish became scarcer, when they’d long since failed their vow to fill that house with children, when the silences between them sometimes lasted hours, when the captain’s wife no longer paced the house, waiting for him, or word of him — an odd thing. They still talked about the letters. RGL became a part of the table that had always been too good to eat on, as important as the deep swirls carved at the top of the legs. She. The simple fact of her once among them, among their things, dusting, opening closet doors, tracing her finger along the frames of the paintings in the front room. Taking a needle — she must have used a needle — and climbing up on the table, walking on her knees to a spot just off the center.

Читать дальше