I printed out the graphs, set them aside, and moved forward with the novel. It became something different, less a staging ground for conceptual pieces, more a straightforward investigation of marriage, of childlessness, of emotional and sexual infidelity. These were common topics, I knew, because they engirdled the lives of many people I knew.

Then a strange thing happened. A guy I had communicated with a little bit online started posting the graphs on his website, and the graphs began to acquire some measure of popularity. People responded to them. There was, briefly, some talk of making a book of the graphs.

At that point, I knew I had to abandon them, or at least move them farther and farther away from the novel I was creating. I went back to the book. The conceptual artist became a secondary character. His sister and her husband came to the fore, along with those questions about marriage and fidelity and suburban emptiness and disappearing youth. The charts were still over my desk, addressing some of the same questions, but they were no longer presiding over the book. The charts were now a set of ideas that had been abandoned by another set of ideas. What better way to explore loneliness?

So, what is loneliness? It’s everything except for the few things that it is not. Last year in the Guardian , Teju Cole made an excellent list of books about loneliness. He picked works by W. G. Sebald, Ralph Ellison, Lydia Davis, and more. All his selections were good, but they were also primarily books about solitude, books about lives without connections. The deeper I got into this book, the more it seemed to be about the opposite: a highly connected life that was nevertheless lonely. (I started to write “that was full of loneliness,” but it seems strange to say that something is full of loneliness. It’s like saying a room is full of emptiness.) The main character, William, is married, without children. He works at an office with coworkers he sees nearly every day. At some point, he starts sleeping with a woman who is not his wife. Does he ever make a meaningful connection? Is it even possible? (There is a moment in the book where he forges a relationship with a boy, the son of an old friend. Briefly, that nourishes him, but it is short-lived as well.) Some might argue that William does what everyone does: he enjoys a series of temporary connections that, over the course of a life, add up. They would not necessarily be wrong. But I would ask them a follow-up question: Add up to what?

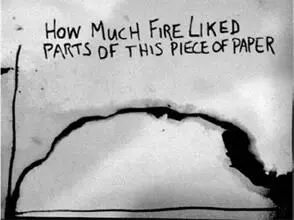

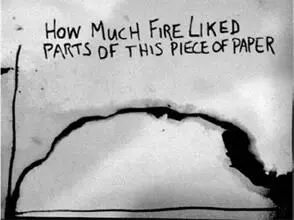

So is that the real question? Is The Slippage an attempt to discover life’s ultimate purpose — or, alternatively, to discover that there isn’t one? That seems grandiose, though it may also be accurate. For most of my own life, I have assumed that the thing that makes life tolerable is meaning, and that the thing that makes meaning is art. Facts are necessary things, but they are just the footholds in the wall you use to climb higher so you can see (or hear) art. And even when you get within reach of art, there’s often not enough of it, or at least not enough of the right kind. I don’t mean to say that you can’t find art you like. That’s not hard to do. But liking is only the beginning. Each and every piece of art, whether a short story or a painting or a pop song, has a specific effect on a certain reader/viewer/listener at a certain time. And art, like medicine, can save or doom. Sometimes the art you like isn’t the art that challenges you. Sometimes the art that challenges you isn’t the art that enlarges you. Sometimes a piece of art grabs you tight but lets you go too soon: disappointment. Sometimes you depend on a piece of art to rescue you and it leaves you cold: more loneliness. If you could locate exactly the right kind of art exactly when you needed it, that would be great. But believing in that kind of efficient delivery requires an implausibly optimistic view of the world and how it operates. How things really work, I think, is that we need to clear away much of what’s created so we can find the things that are meaningful to us. And so, in the novel, I found a role for the chart artist by setting up a subplot in which two forces are locked in battle: art and fire. Both are refining forces, though one is an agent of creation and the other an agent of destruction. At one point, following a rash of arsons in town, the chart artist develops what some might call an unhealthy obsession with fire, and then translates his obsession into artwork:

I liked that graph when I thought of it. It seemed funny without also being mean. I even considered making it the sole graph in the body of the novel, reproduced below a normal old paragraph of prose. Instead, it ended up here. Later, it occurred to me that it (along with many of the other graphs) actually encodes a great deal of anxiety on my part about how artwork is received. This graph, the fire graph, is a metaphor of enthusiasm. It speaks to the odd process by which an audience (of critics, say, or students, or the reading public, whatever that means) does or does not take to a book.

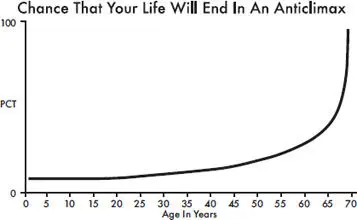

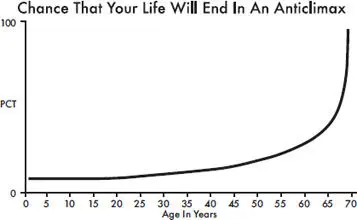

What happens after a book comes out? People read it and have reactions, and some of them express those reactions, in print or online. It’s a perfectly workable process. But it’s also a strange process, reductive and confusing. Earlier, in telling my story about the reading I attended as a young writer, I mentioned that audience members asked two questions that have remained with me. The first, as I have said, was about connection. The second was this: “Is this your best book?” A young man asked that question. I believe he was wearing overalls, which is neither here nor there. The older (but still young) writer tilted his head as if he was thinking. He scratched his not quite beard. His answer was this: “No.” The audience laughed. “What I mean,” he said, “is that I think the best is yet to come.” Once more my heart fell a little, not because I didn’t see the wisdom of the writer’s answer, but because I thought I saw something false flickering at the heart of it. The chances that your next work will always be better than your last are slim indeed. Over the course of a career, work both draws closer to inspiration and moves farther away from it. Believing in steady improvement is an operating fiction. And yet, pride tells you to be more proud of the most recent work than the work that came before it, and to pretend that it is the most completely realized portrait of your inner state. Again, much of this becomes irrelevant if an artist signs up for a lifetime subscription to his or her own artwork. Long fallow periods can be followed by a new flowering. Movements can be profitably lateral instead of aggressively, deceptively vertical.

After I left that reading, I went to a restaurant and did some doodling on a napkin. One of the things I doodled was a graph that later inspired a piece of work by the conceptual artist who did not quite become the center of this book. It seems like an appropriate place to end.

Author Recommendations

THIS BOOK IS ABOUT MARRIAGE: other things, too, but maybe mainly marriage. Here are some other works that also look closely at the idea.

Frederick Barthelme, Second Marriage . Frederick’s brother Donald has a grand literary reputation, deservedly so. Fewer people, maybe, know about Frederick. His novels are more realistic and also more comic, which combine to make people feel that they’re somehow miniatures. They’re not. They see sharply and they say what they see just as sharply.

Читать дальше