“Which one am I?” William said.

Louisa did not answer. Something in William’s tone held her silent. And then William was silent again, also, and the girl put her arms around the neck of the mocking boy and then hooked a finger through one of the belt loops of the pleading boy and then took his cigarette from him and flicked it an impressive distance across the parking lot. It went like a shooting star through the darkness and sent off a shower of sparks when it landed. Then the mocking boy got back into the car and changed the radio and the girl started to kiss the pleading boy and the pleading boy clasped his hands at the lower part of her back and the two of them went at an angle against the edge of the hood.

“Is this for our benefit?” Louisa said.

“Doesn’t seem so,” William said.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I just needed my strength back. Do you know what that feels like? I was doing it for us, in a strange way, for you and me. I wanted to be better. For the first time in years, I felt like we were building toward something.”

“We sure were.”

She winced, her face childlike and mournful. “I didn’t mean the house.”

“I know what you didn’t mean,” William said, and turned the key to start the engine. But before he backed the car out of the space, he lifted his right hand, as if he were indicating the height of something or someone, and then brought the flat of his palm down as hard as he could on the top of the steering wheel. It juddered and for a second he thought he had broken something.

“Jesus,” Louisa said.

“I hate this car,” he said. He said it like the assault was purposeful. But the act had surprised him, and when he went to back up he bumped the lower half of the wheel and the horn honked, once, for a fraction of a second at most. The girl and the pleading boy turned toward them and turned away just as quickly and that’s when William thought he recognized her: she looked like the cashier at the Red Barn, the daughter of the owner. But then she stared defiantly at William and Louisa as if she could see them, though he didn’t think she could, and this time she didn’t look like that girl at all, and William backed out and left the parking lot. The boy in the car shouted something at them, and William waved good-bye with his hand, which was beginning to hurt.

Louisa started to speak a few times. She asked him if she’d made a mistake by saying anything. She told him that it had been less than nothing. She reassured him that she was happy with how things were, now that all the trouble between them had evaporated. William was hardly driving anymore, just resting his left hand on the wheel as they rolled onto their street. The Brookers were hosting a small gathering in warm light and everyone was smiling. The Morgan place looked just like William’s but wasn’t. Stevie and Emma’s house was dark, and was no longer theirs at any rate. They had moved to Arizona, baby in tow, so that Stevie could oversee corporate creative. On the day the moving truck had come to cart their things away, William had walked across the street and given Stevie a handshake and a pat on the back, feeling as though the two of them had shared something, even if he was the only one who knew it. “Hold down the fort,” Stevie had said. William had saluted, just as he had at the garage door, not feeling as idiotic about it this time.

William pulled into the driveway and got out without turning off the car. An orchestra of birds tuned up in the branches overhead. He unlocked the front door and pushed into the house with his shoulder. He heard claws scrabbling on the tile; the dog bounded out of the hall and hit William hip-height. “Good boy,” he said, bending down to scratch the dog’s head. This one was black, with a white streak running down the forehead to the nose, and he slept in a crate in the garage. William went into the bedroom, where he lowered himself onto the bed and looked out to the driveway. Louisa was sitting in the SUV with the door open, illuminated by the interior light, still as a statue.

He closed his eyes and time passed, not very much, maybe, but enough that he began to feel its weight upon him. When he opened his eyes Louisa was out of the car, facing him, just a few feet from the house. She was backlit by the headlights of the car, which meant that she was looking at her own reflection and he was lost behind the glare. He wondered if she could see him at all. She made a spider of her hand and pressed it to the outside of the windowpane. William stood and went to the window. He waved with his sore hand, receiving no acknowledgment in return, and then lowered the hand to hip height, made a spider of his own, paired it with hers, across the glass, and stood there squinting at her silhouette as the light ran away from her in streaks.

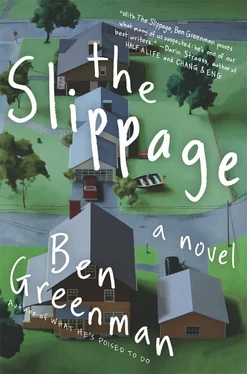

Movies have credits, as do record albums. The contributions of others are recognized explicitly. Books, being strange, operate under the fiction that they’re produced by a single individual. As that individual, it falls to me to recognize the rest of the people who helped this book into being, in ways both large and small, subtle and straightforward, abstract and concrete, willing and somewhat less than willing. I’d like to thank my wife, Gail; my kids, Daniel and Jake; my parents, Richard and Bernadine; my brothers, Aaron and Josh; my friends Lauren and Rhett and Nicole and Charlotte and Nicki and Todd and Harold and Steve; my agents, Jim Rutman and Ira Silverberg; my boss at work, David Remnick; my colleagues at work; and, finally, last and most, my editor, Cal Morgan. I’d also like to thank all married men and women for living rewarding, frustrating, comforting, and disconcerting lives that are frequently in flux and too infrequently in focus.

P.S. Insights, Interviews & More…

About the author

A Conversation with Ben Greenman

About the book

Plotting a Point

Read on

Author Recommendations

A Conversation with Ben Greenman

Where do you live?

In Brooklyn, right near where the spacecraft Barclays Center landed.

And yet, you chose to write about the suburbs. Why?

Well, I grew up in the suburbs, and I think I’m still there in some ways, in my mind. I got conditioned to believe certain things about human interaction, or the lack of it. In the suburbs, distance works differently. There’s more silence (which can be either paralyzing or erotic) and more meaninglessness (which can be either liberating or crushing).

But that’s about the book, and this is about the author. Let me ask you about the relationship between your life and your writing. How do you feel about writing autobiographically?

Generally, I’ve been against it. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve wanted to look more closely at the kind of life I have, even if that doesn’t exactly mean looking at my own life. As life goes on, it becomes more and more about weighing responsibilities against diminished (or narrowed) freedoms. I have accepted that in my marriage, in fatherhood, in work. But I haven’t explored the same principle in my writing. For a long time, I wrote with a maximum of freedom, meaning trickery and metafictional evasion. I told myself that taking fairly straightforward aim at the lives of my characters was less exciting, though maybe I was just avoiding it because it was less comfortable.

Do you worry about hurting people close to you when you write?

Yes. I know a writer (I won’t say who) who seems to take delight in calling out friends and lovers in his or her fiction. Is that bravery? Is that narcissism? I suppose I am not answering the question so much as asking more questions.

Читать дальше