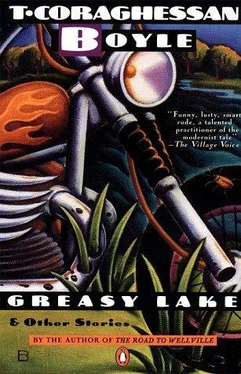

T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1986, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Greasy Lake and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1986

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Greasy Lake and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

says these masterful stories mark

's development from "a prodigy's audacity to something that packs even more of a wallop: mature artistry." They cover everything, from a terrifying encounter between a bunch of suburban adolescents and a murderous, drug-dealing biker, to a touching though doomed love affair between Eisenhower and Nina Khruschev.

Greasy Lake and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Greasy Lake and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Cramps. A spasm so violent it jerks his fingers from the strings. He begins again, his voice quavering, shivered: “Got to keep moving, got to keep moving, / Hellbound on my trail.” And then suddenly the voice chokes off, gags, the guitar slips to the floor with a percussive shock. His bowels are on fire. He stands, clutches his abdomen, drops to hands and knees. “Boy’s had too much of that Mexican,” someone says. He looks up, a sword run through him, panting, the shock waves pounding through his frame, looks up at the pine plank, the barrels, the cold, hard features of the girl with the silver necklace in her hand. Looks up, and snarls.

All Shook Up

About a week after the FOR RENT sign disappeared from the window of the place next door, a van the color of cough syrup swung off the blacktop road and into the driveway. The color didn’t do much for me, nor the oversize tires with the raised white letters, but the side panel was a real eye-catcher. It featured a lifesize portrait of a man with high-piled hair and a guitar, beneath which appeared the legend: Young Elvis, The Boy Who Dared To Rock. When the van pulled in I was sitting in the kitchen, rereading the newspaper and blowing into my eighth cup of coffee. I was on vacation. My wife was on vacation too. Only she was in Mill Valley, California, with a guy named Fred, and I was in Shrub Oak, New York.

The door of the van eased open and a kid about nineteen stepped out. He was wearing a black leather jacket with the collar turned up, even though it must have been ninety, and his hair was a glistening, blue-black construction of grease and hair spray that rose from the crown of his head like a bird’s nest perched atop a cliff. The girl got out on the far side and then ducked round the van to stand gaping at the paint-blistered Cape Cod as if it were Graceland itself. She was small-boned and tentative, her big black-rimmed eyes like puncture wounds. In her arms, as slack and yielding as a bag of oranges, was a baby. It couldn’t have been more than six months old.

I fished three beers out of the refrigerator, slapped through the screen door, and crossed the lawn to where they stood huddled in the driveway, looking lost. “Welcome to the neighborhood, I said, proffering the beers.

The kid was wearing black ankle boots. He ground the toe of the right one into the pavement as if stubbing out a cigarette, then glanced up and said, “I don’t drink.”

“How about you?” I said, grinning at the girl.

“Sure, thanks,” she said, reaching out a slim, veiny hand bright with lacquered nails. She gave the kid a glance, then took the beer, saluted me with a wink, and raised it to her lips. The baby never stirred.

I felt awkward with the two open bottles, so I gingerly set one down on the grass, then straightened up and took a hit from the other. “Patrick,” I said, extending my free hand.

The kid took my hand and nodded, a bright wet spit curl swaying loose over his forehead. “Joey Greco,” he said. “Glad to meet you. This here is Cindy.”

There was something peculiar about his voice — tone and accent both. For one thing, it was surprisingly deep, as if he were throwing his voice or doing an impersonation. Then too, I couldn’t quite place the accent. I gave Cindy a big welcoming smile and turned back to him. “You from down South?” I said.

The toe began to grind again and the hint of a smile tugged at the corner of his mouth, but he suppressed it. When he looked up at me his eyes were alive. “No,” he said. “Not really.”

A jay flew screaming out of the maple in back of the house, wheeled overhead, and disappeared in the hedge. I took another sip of beer. My face was beginning to ache from grinning so much and I could feel the sweat leaching out of my armpit and into my last clean T-shirt.

“No,” he said again, and his voice was pitched a shade higher. “I’m from Brooklyn.”

Two days later I was out back in the hammock, reading a thriller about a double agent who turns triple agent for a while, is discovered, pursued, captured, and finally persuaded under torture to become a quadruple agent, at which point his wife leaves him and his children change their surname. I was also drinking my way through a bottle of Chivas Regal Fred had given my wife for Christmas, and contemplatively rubbing tanning butter into my navel. The doorbell took me by surprise. I sat up, plucked a leaf from the maple for a bookmark, and padded round the house in bare feet and paint-stained cutoffs.

Cindy was standing at the front door, her back to me, peering through the screen. At first I didn’t recognize her: she looked waifish, lost, a Girl Scout peddling cookies in a strange neighborhood. Just as I was about to say something, she pushed the doorbell again. “Hello,” she called, cupping her hands and leaning into the screen.

The chimes tinnily reproduced the first seven notes of “Camp-town Races,” an effect my wife had found endearing; I made a mental note to disconnect them first thing in the morning. “Anybody home?” Cindy called.

“Hello,” I said, and watched her jump. “Looking for me?”

“Oh,” she gasped, swinging round with a laugh. “Hi.” She was wearing a halter top and gym shorts, her hair was pinned up, and her perfect little toes looked freshly painted. “Patrick, right?” she said.

“That’s right,” I said. “And you’re Cindy.”

She nodded, and gave me the sort of look you get from a haberdasher when you go in to buy a suit. “Nice tan.”

I glanced down at my feet, rubbed a slick hand across my chest. “I’m on vacation.”

“That’s great,” she said. “From what?”

“I work up at the high school? I’m in Guidance.”

“Oh, wow,” she said, “that’s really great.” She stepped down off the porch. “I really mean it — thats something.” And then: “Aren’t you kind of young to be a guidance counselor?”

“I’m twenty-nine.”

“You’re kidding, right? You don’t look it. Really. I would’ve thought you were twenty-five, maybe, or something.” She patted her hair tentatively, once around, as if to make sure it was all still there. “Anyway, what I came over to ask is if you’d like to come to dinner over at our place tonight.”

I was half drunk, the thriller wasn’t all that thrilling, and I hadn’t been out of the yard in four days. “What time?” I said.

“About six.”

There was a silence, during which the birds could be heard cursing one another in the trees. Down the block someone fired up a rotary mower. “Well, listen, I got to go put the meat up,” she said, turning to leave. But then she swung round with an afterthought. “I forgot to ask: are you married?”

She must have seen the hesitation on my face.

“Because if you are, I mean, we want to invite her too.” She stood there watching me. Her eyes were gray, and there was a violet clock in the right one. The hands pointed to three-thirty.

“Yes,” I said finally, “I am.” There was the sound of a stinging ricochet and a heartfelt guttural curse as the unseen mower hit a stone. “But my wife’s away. On vacation.”

I’d been in the house only once before, nearly eight years back. The McCareys had lived there then, and Judy and I had just graduated from the state teachers’ college. We’d been married two weeks, the world had been freshly created from out of the void, and we were moving into our new house. I was standing in the driveway, unloading boxes of wedding loot from the trunk of the car, when Henry McCarey ambled across the lawn to introduce himself. He must have been around seventy-five. His pale, bald brow swept up and back from his eyes like a helmet, square and imposing, but the flesh had fallen in on itself from the cheekbones down, giving his face a mismatched look. He wore wire-rim glasses. “If you’ve got a minute there,” he said, “we’d like to show you and your wife something.” I looked up. Henry’s wife, Irma, stood framed in the doorway behind him. Her hair was pulled back in a bun and she wore a print dress that fell to the tops of her white sweat socks.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.