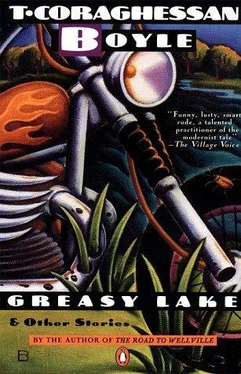

T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1986, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Greasy Lake and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1986

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Greasy Lake and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

says these masterful stories mark

's development from "a prodigy's audacity to something that packs even more of a wallop: mature artistry." They cover everything, from a terrifying encounter between a bunch of suburban adolescents and a murderous, drug-dealing biker, to a touching though doomed love affair between Eisenhower and Nina Khruschev.

Greasy Lake and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Greasy Lake and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The door stands open. For a long moment he hesitates, watching himself in the window. His face is crazy, the glint of his glasses masking his eyes, a black spot of grease on his forehead. What am I doing? he thinks. Then he wipes his hands on his pants and swings his legs through the doorway.

At first he can see nothing: the lights are out, the interior dim. There are sounds from the rear of the shop, the scrape of objects being dragged across the floor, a thump, voices. “I got no insurance, I tell you.” Plaintive, halting, the voice of the German woman. “No money. And now I owe nearly two thousand dollars for all this stock”—more heavy, percussive sounds—“all gone to waste. ”

Now he begins to locate himself, objects emerging from the gloom, shades drawn, a door open to the sun all the way down the corridor in back. Christ, he thinks, looking round him. The display racks are on the floor, toppled like trees, cans and boxes and plastic packages torn open and strewn from one end of the place to the other. He can make out the beer cooler against the back wall, its glass doors shattered and wrenched from the hinges. And here, directly in front of him, like something out of a newsreel about flooding along the Mississippi, a clutter of overturned tables, smashed chairs, tangled rolls of butcher’s paper, the battered cash register and belly-up meat locker. But all this is nothing when compared with the swastikas. Black, bold, stark, they blot everything like some killing fungus. The ruined equipment, the walls, ceiling, floors, even the bleary reproductions of the Rhine and the big hand-lettered menu in the window: nothing has escaped the spray can.

“I am gone,” the German woman says. “Finished. Four times is enough. ”

“Eva, Eva, Eva.” The second voice is thick and doleful, a woman’s voice, sympathy like going to the bathroom. “What can you do? You know how Mike and I would like to see those people in jail where they belong—”

“Animals,” the German woman says.

“We know it’s them — everybody on the block knows it — but we don’t have the proof and the police won’t do a thing. Honestly, I must watch that house ten hours a day but I’ve never seen a thing proof positive.” At that moment, Mrs. Tuxton’s head comes into view over the gutted meat locker. The hair lies flat against her temples, beauty-parlor silver. Her lips are pursed. “What we need is an eyewitness.”

Now the German woman swings into view, a carton in her arms. “Yah,” she says, the flesh trembling at her throat, “and you find me one in this… this stinking community. You’re a bunch of cowards — and you’ll forgive me for this, Laura — but to let criminals run scot-free on your own block, I just don’t understand it. Do you know when I was a girl in Karlsruhe after the war and we found out who was the man breaking into houses on my street, what we did? Huh?”

Calvin wants to cry out for absolution: I know, I know who did it! But he doesn’t. All of a sudden he’s afraid. The vehemence of this woman, the utter shambles of her shop, Ormand, Lee Junior, the squawk of the police radio: his head is filling up. It is then that Mrs. Tuxton swivels round and lets out a theatrical little gasp. “My God, there’s someone here!”

In the next moment they’re advancing on him, the German woman in a tentlike dress, the mean little eyes sunk into her face until he can’t see them, Mrs. Tuxton wringing her hands and jabbing her pointy nose at him as if it were a knife. “You!” The German woman exclaims, her fists working, the little feet in their worn shoes kneading the floor in agitation. “What are you doing here?”

Calvin doesn’t know what to say, his head crowded with numbers all of a sudden. Twenty thousand leagues under the sea, a hundred and twenty pesos in a dollar, sixteen men on a dead man’s chest, yo-ho-ho and one-point-oh-five quarts to a liter. “I… I—” he stammers.

“The nerve,” Mrs. Tuxton says.

“Well?” The German woman is poised over him now, just as she was on the day she slapped the soda from his hand — he can smell her, a smell like liverwurst, and it turns his stomach. “Do you know anything about this, eh? Do you?”

He does. He knows all about it. Jewel knows, Lee Junior knows, Ormand knows. They’ll go to jail, all of them. And Calvin? He’s just an old man, tired, worn out, an old man in a wheelchair. He looks into the German woman’s face and tries to feel pity, tries to feel brave, righteous, good. But instead he has a vision of himself farmed out to some nursing home, the women in the white caps prodding him and humiliating him, the stink of fatality on the air, the hacking and moaning in the night “I’m… I’m sorry,” he says.

Her face goes numb, flesh the color of raw dough. “Sorry?” she echoes. “Sorry?”

But he’s already backing out the door.

Stones in My Passway, Hellhound on My Trail

I got stones in my passway

and my road seems black as night.

I have pains in my heart,

they have taken my appetite.

— ROBERT JOHNSON (1914?-1938)Saturday night. He’s playing the House Party Club in Dallas, singing his blues, picking notes with a penknife. His voice rides up to a reedy falsetto that gets the men hooting and then down to the cavernous growl that chills the women, the hard chords driving behind it, his left foot beating like a hammer. The club’s patrons — neld hands and laborers — pound over the floorboards like the start of the derby, stamping along with him. Skirts fly, straw hats slump over eyebrows, drinks spill, ironed hair goes wiry. Overhead two dim yellow bulbs sway on their cords; the light is suffused with cigarette smoke, dingy and brown. The floor is wet with spittle and tobacco juice. From the back room, a smell of eggs frying. And beans.

Huddie Doss, the proprietor, has set up a bar in the corner: two barrels of roofing nails and a pine plank. The plank supports a cluster of gallon jugs, a bottle of Mexican rum, a pewter jigger, and three lemons. Robert sits on a stool at the far end of the room, boxed in by men in kerchiefs, women in calico. The men watch his fingers, the women look into his eyes.

It is 1938, dust bowl, New Deal. FDR is on the radio, and somebody in Robinsonville is naming a baby after Jesse Owens. Once, on the road to Natchez, Robert saw a Pierce Arrow and talked about it for a week. Another time he spent six weeks in Chicago and didn’t know the World’s Fair was going on. Now he plays his guitar up and down the Mississippi, and in Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas. He’s never heard of Hitler and he hasn’t eaten in two days.

When he was fifteen he watched a poisoned dog tear out its entrails. It was like this:

They were out in the fields when a voice shouted, “Loup’s gone mad!” and then he was running with the rest of them, down the slope and across the red dust road, past the shanties and into the gully where they dumped their trash, the dog crying high over the sun and then baying deep as craters in the moon. It was a coonhound, tawny, big-boned, the color of a lion. Robert pushed through the gathering crowd and stood watching as the animal dragged its hindquarters along the ground like a birthing bitch, the ropy testicles strung out behind. It was mewling now, the high-pitched cries sawing away at each breath, and then it was baying again, howling death until the day was filled with it, their ears and the pits of their stomachs soured with it. One of the men said in a terse, angry voice, “Go get Turkey Nason to come on down here with his gun,” and a boy detached himself from the crowd and darted up the rise.

It was then that the dog fell heavily to its side, ribs heaving, and began to dig at its stomach with long racing thrusts of the rear legs. There was yellow foam on the black muzzle, blood bright in the nostrils. The dog screamed and dug, dug until the flesh was raw and its teeth could puncture the cavity to get at the gray intestine, tugging first at a bulb of it and then fastening on a lank strand like dirty wash. There was no sign of the gun. The woman beside Robert began to cry, a sound like crumpling paper. Then one of the men stepped in with a shovel in his hand. He hit the dog once across the eyes and the animal lunged for him. The shovel fell twice more and the dog stiffened, its yellow eyes gazing round the circle of men, the litter of bottles and cans and rusted machinery, its head lolling on the lean, muscular neck, poised for one terrible moment, and then it was over. Afterward Robert came close: to look at the frozen teeth, the thin, rigid limbs, the green flies on the pink organs.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.