There were children everywhere, scattered and released from school; a pavement stall selling newspapers.

They were approaching the market; the tramlines here met and gleamed.

“Turn left and stop there,” said Jayojit, pointing to the opposite side of the road.

They waited for a tram to pass, the taxi already tensed to compete with a neighbouring car to make the first movement. When the taxi jerked forward, Bonny clutched the seat with his fingers, puzzled, but the impulse to race was spent almost as soon as it was surrendered to, and they were no more in motion.

“How much?” Jayojit asked, opening the door and stepping out. “Careful, Bonny, don’t get out on that side”; afraid because of the buses like juggernauts.

The meter said nine rupees.

“Tero taka,” said the driver. Thirteen rupees; lucky number. Jayojit took out the notes from his wallet and handed them to the driver — they were from the second wad of cash he’d got across the counter after coming here, and the perforations from where the staples had been violently prised open still showed — who counted them, and fished in his pocket for change. There seemed to be confusion about whether, indeed, the driver had the change or not.

“Fourteen, fifteen,” he said finally, as if muttering a charm to the counting of a rupee and two fifty paisa coins, and completed the transaction by dropping them into Jayojit’s palm.

He turned and found that Bonny wasn’t there. Where in the world is he? He went through the narrow passage between two stalls, and saw a boy in a t-shirt standing before a shop: Bonny.

“Ei khokababu,” said a voice, “ei khokababu!”

“Don’t disappear like that,” said Jayojit to the unsurprised boy. “Okay?”

Bonny assented by saying nothing and lifting his eyes to look at his father; then he rubbed one eye with the back of a hand.

“Dada — take a look at these shirts!”

Bonny was wearing sneakers; he must be hot — it might be an idea to buy him a pair of sandals. Where was Bata?

They went past vendors selling fruit on beds of straw. Mangoes had just come into season, piled pale green on baskets, but theirs was a peculiar family, because the Admiral couldn’t stand mangoes and the mess they made, and Jayojit had inherited his father’s fastidiousness; his mother, over the last few years, had become stoic; and the money she thus saved compensated somewhat for her yearning for the first langra and himsagar. Finally, Jayojit paused and went inside a store and asked for Dove soap. His mother had said “Dove” wistfully when he’d asked her which soap they used these days; it used to be Pears, he knew, but on this visit, like a new discovery, it was Dove; and since it was more expensive, a rare indulgence. As if by coincidence, he now saw an advertisement on one of the glass windows of the cabinets inside. The model, in the make-believe opulence of her bath, looked familiar, but she couldn’t be, she was too young; he’d stopped noticing models for years now; the last model he could remember — and he was surprised at the trivial information his mind retained — was called Anne Bredemeyer. “Dove,” he said, without knowing who would respond; there were three men behind the counter who themselves had the searching air of visitors.

“Give us a Dove soap!” said a man in kurta and pyjamas to someone at the back, then turned to Jayojit, “Anything else?”

Jayojit looked at the medicine racks behind the man, looking back at Bonny to see if he was on the steps, noted the fan overhead, and scanned the shelves for shampoo. But it was conditioner he wanted; his hair was greying; the grey had been seeping into the black. But he didn’t see any conditioner, unless it was disguised as something else; he saw bottles that said “frequent use” and “for greasy hair.” His hair, if anything, was too dry. About five or more seconds had passed since the thin man had said “Aar kichhu?”—and now Jayojit found himself saying, “Colgate toothpaste achhe?” almost ironically, then pondering on a suitable reply to “Chhoto na bado?”—“Small or large?”; and as an afterthought, adding “talcum powder.”

He’d seen a commercial on television the day before yesterday in which a busybody of a child was brushing his teeth with Colgate.

“Which powder?” asked the man behind the counter, who was shrunken but fastidious.

“Any will do,” confessed Jayojit. “Pond’s,” he said; the word had just come to him out of nowhere.

“Pond’s,” the man said. He turned. “Jodu,” he called, “Pond’s talcum powder de!”

Another man came out from behind a cupboard and looked at Jayojit with the interested equanimity of one looking at himself in a mirror.

“Pond’s?” he said, as if he was not sure if he’d heard correctly, and retreated again.

More fumblings.

“That’s seventy rupees,” said the man at last, writing numbers secretively on the back of an envelope.

On the way back they stopped at a bookshop that Jayojit noticed behind a photocopying and STD booth. The sky had darkened a few minutes before they entered. The man who ran the shop, dressed in a creased dhoti and kurta, regarded the rain without wonder or accusation as it began to fall in isolated drops.

“Baba, I wanna touch it,” cried Bonny, jumping in the doorway by the bookshelves.

“Go on then.”

The shopkeeper looked up once again — as if at a noise in the distance — and looked downward. The lane was subsumed in a gloom which made the colours of the unremarkable multi-storeyed building before them more visible. “But the rains aren’t supposed to start till two weeks later,” thought Jayojit, irritated, thinking of the weather fronts and insubstantial bands of high pressure building up over the South and the coasts of Kerala; grateful, too, for the breeze. Contemptuous, he turned his back to the drama of the rains. He looked, unseeing, at the rows of Penguin Indias, and registered, remotely, as one would the words of an exotic language, the Marquezes, Vargas Llosas; next to them, slim books of horoscopes; arranged for a reader who wasn’t very clear about what he was looking for.

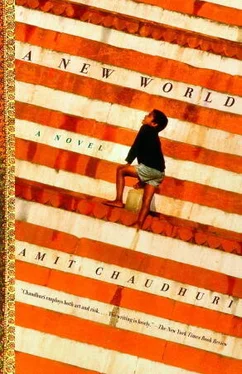

He began to look for a book at random; noted the motto “Everyman, I will be thy guide” ; stared, with some scepticism, at some of the books by Indian writers; “They not only look light, they feel lightweight as well,” he thought, weighing one in his hand; he picked up a new paperback of A Suitable Boy with a theatrical air which there was no one to note. The last book he’d read was a volume treading, in the fog of post-structuralist theory, a tightrope between history and Keynesian economics; and he was going to give it a bad review for the university humanities journal. A colleague, an Italian American called Antonio who edited the journal, had sent it to him with a note: “Dear J, I know there are worse things in life than reading a deconstruction of classical economic theory (tell me about it!) but things aren’t half as bad as you think. Snap out of it, pal, and send me 1,500 words when you feel like it. Don’t leave it till the millennium. Best, Tony.” Antonio, settled with three children, married to a half-Vietnamese, half-French American, setting up the book for a bad review, knowing full well Jayojit’s distaste for airy-fairy “theory.” But Bonny was getting his t-shirt damp with the spray. Afraid of being reprimanded by his mother (he feared not so much his mother’s words as her silences), Jayojit said:

“Come in here, you!”

“Oh, baba!”

He hopped into the shop, throwing a glance at the books stacked everywhere. Jayojit brushed the moisture from the boy’s hair with his fingers. “Stand still!” Then: “Turn round”; the boy turning not so much obediently as displaying his swiftness; yet the tiniest bit afraid of his father’s brusqueness. “Okay.” He was thin now with burnt-up energy, but when he’d been born he’d been seven and a half pounds and his grandmother, his mother’s mother, had said, after the long night: “Ki bonny baby eta!” Yes, Bonny had been pink (“a little white mouse,” his mother had called him), with a hint of black hair which Amala repeatedly admired. They’d been in Claremont then, the nursing home had been on the outskirts, and the grandmother had come to be with her daughter. A week later, when it had come home, Jayojit had taken footage of the child, its first movements in the cot between the double bed and cupboard, and moments captured from its spells of sleep, on a camcorder, dipping into the baby’s life with the lens for two days, and then made videos for both sets of parents, who’d noted both the baby and the beauty of the house. The shopkeeper seemed not to notice the boy and the thirty-seven-year-old father’s exchange; keeping a vigil, he stared at Jayojit, his eyelids flickered respectfully, and, after opening his mouth to yawn, turned back to the books he was stacking on the table.

Читать дальше