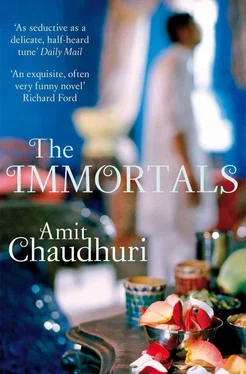

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He liked Bengali food, though. The luchis were interesting. He put the last piece in his mouth.

‘Laxmiji, some more?’ asked Mrs Sengupta, sitting up. ‘John,’ she admonished the bearer, ‘what are you doing, see, the saab’s plate is empty.’

Laxmi Ratan Shukla raised the palm of one hand. ‘Bas,’ he said.

Two years later, as they were going down the curve of Haji Ali — a grey day, with very few cars on the road, when it seemed it was going to rain — Mrs Sengupta said a little resignedly, ‘Do you know, I don’t think he’s ever going to let me cut a record.’ She didn’t expect a reply from her husband; his policy, she knew, was long term: Wait and see. She was the opposite; she was impatient; there was no point in waiting and watching.

Dark clouds hung over the twin towers of Samudra Mahal. She stirred restlessly in her seat, and he gave no answer. Then, as the car left the panorama of the steel-grey sea behind, he said, ‘Well, let us see. You’ve had the new teacher, Jairam, a little over a year now. I’ll speak to Shukla again.’

She’d got rid of Motilalji, partly because of his drink-induced irateness, and this new man, balding, enthusiastic, had taken his place. Jairam came on Laxmi Ratan Shukla’s recommendation. He was a family man; he had four children. The third was a daughter, an eight-year-old called Kamala, whom he brought home with him one day. She was dark and quiet. ‘Brij Mohan’, said Jairam, referring to a well-known aficionado and concert organiser, ‘says she sings like Lata. In ten years. .’ The girl was quiet, but sang without much prompting. ‘Gao beti,’ said Jairam — they say that men with a paunch have a cheerful disposition, and this was certainly true of Jairam. ‘Sing a bhajan for behanji.’ She launched, in her thin voice, into a Surdas bhajan.

O Govind, O Gopal,

Keep a refuge for me, I

’ve pledged you my life.

The little girl stared into the distance as she sang. The parrot-like quality was almost touching. But the Lata-like timbre of the child’s voice grated on Mrs Sengupta’s ears; it inflamed her, this schooling in replicating this voice, and it also made her despair for Kamala. She imagined that this was what Lata herself might have looked like when she was a child, and had been taken by Dinanath Mangeshkar (or so the myth went) to audition for a film-maker; and he had been mesmerised. Lata, too, would have been like this child in her orange frock, expectant and unknown, the progeny of a struggling musical family. But Kamala was not Lata; neither in identity, nor in talent. She was just another girl being asked to live up to her father’s dreams.

Jairam was himself a competent teacher, but Mrs Sengupta wasn’t impressed by him. He seemed to lack purpose — except, perhaps, where his daughter was concerned. On that particular day, he’d talked continually about his sons and his daughter, sipped tea and gratefully accepted the snacks offered to him, and gossiped about other singers and music teachers; the morning, Mrs Sengupta had thought privately, had become a family affair. Mrs Sengupta didn’t like too much conviviality during her music lesson.

It began to rain now, on the office buildings between Worli and Prabhadevi. Under the dark clouds, the sky was changing colour; as on the wing of a bird, one colour fades or deepens into another. He is used to giving orders, thought Mrs Sengupta of the man beside her, but how incredibly cautious and accommodating he seems before Laxmi Ratan Shukla! The large drops clattered onto the windshield of the Ambassador and melted against the glass. With a tick-tick sound the wipers came to life, and through their swathes the road between Worli and Prabhadevi became visible.

* * *

WHEN THE FIRST promotion had come after Mr Deb’s death, to Company Secretaryship, almost the first people to know in Bombay were the Neogis. The Senguptas still had few friends in the city. This friendship was a result of an encounter in the fifties, in a foreign land, in England, where Prashanta Neogi had travelled to study art; Apurva Sengupta to peruse Company Law. The story was that they’d met, in fact, on the ship. Two lonely Indians on deck, they’d begun to talk; and Prashanta Neogi still spoke about it with a wifely shrug of the shoulders that went oddly with his large frame. Later, they’d shared a cold room in Croydon for a couple of days, and, the first morning, to his horror, Prashanta had discovered that Apurva had used his toothbrush by mistake. Prashanta spoke of this with bafflement and indulgence, as if it had sealed their friendship for the future.

The Neogis lived on the outskirts; in a house on a lane off Gorbunder Road. A low two-storeyed building; a small dusty driveway; the railway lines visible beyond the houses on the opposite side of the road — it was a very different kind of life from the one the Senguptas had now begun to lead. The Neogis were tenants who occupied the ground-floor flat; their lives were casually artistic and unconventional; neither Prashanta nor his wife Nayana ever wore anything but hand-crafted clothes; they smoked heavily and drank in the evening as a matter of course; there were long, involved sessions of bridge and rummy in the evening. There were almost always guests in the house — filmmakers who were passing through; painters — and one might catch them in the morning, wandering in their pyjamas. ‘But that’s the way we like it,’ Nayana would say, a woman with a sweet, round Bengali face, made unusual and striking by her height and largeness. ‘We like people in our house.’ ‘People!’ Mallika Sengupta would say to her husband. ‘It’s a strange house — not a moment of silence!’

The Neogis were the first to know. Mallika Sengupta called them and said: ‘I have some news.’

‘Yes, tell me all about it!’ said Nayana, feigning eagerness.

‘Apurva has had a promotion. Poor Mr Deb died suddenly, you know. Mr Dyer called Apurva day before yesterday to his office and told him to take Mr Deb’s position.’

‘O that’s wonderful!’ sang Nayana; she sounded pleased. Both she and her husband had a soft spot for Apurva, the ‘boy’ who’d once erred in using Prashanta’s toothbrush. ‘Thank God that man Dyer has some sense! The things I hear about him. .’

Of course, Nayana and her husband had an interest in the matter. Their dear friend Apurva’s former boss — Kishen Arora — whose company he’d left to join this one: this former boss was a dear friend of theirs. Kishen Arora: a man from Delhi, with a squint, a tall Czech wife, and a cultivated manner. A man who said little. Apurva had realised that his prospects, working under him, were bleak. But when it came to changing jobs, the Neogis had dissuaded him: ‘That’s what Kishen’s like , silly! He seems distant. But he’s a man of his word.’

That’s why every advance Apurva Sengupta made in his new job brought the Neogis both happiness and a momentary embarrassment.

* * *

THAT DAY, as Motilalji and Shyamji came out from Mrs Sengupta’s house, Shyamji had wondered for a moment what the meaning of the expedition had been. Why had Motilalji taken him there?

He was difficult to fathom, this man.

The answer was obvious, though. Motilalji wanted to impress his brother-in-law. He wanted to show off.

Pyarelal was sitting on the divan in Motilalji’s house. He seemed to have been sitting there for a while; he had been eating something. When Shyamji saw him, he blanched slightly; the man always made his pulse beat a little faster. As the two entered, Pyarelal got up, and went quickly to the kitchen to deposit his plate and glass. Always busy, darting from here to there, as if he didn’t have a moment’s respite; as if he wasn’t the parasite he really was. Shyamji couldn’t stand his nervous energy, his constant compulsion to turn the humdrum into theatre. But Shyamji called out to him wearily:

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.