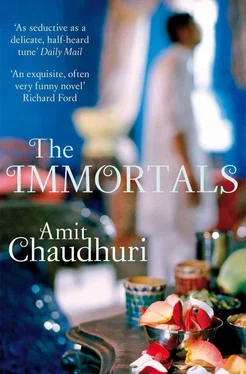

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Jumna, to whom Mrs Sengupta used to confide her sorrow, her anxiety, had changed. Her body hadn’t aged; but her face had. Seven years ago, her husband, the bewda, had knocked her front teeth out. Each time there was a headline that said, Seven Die in Country Liquor Tragedy, the Senguptas thought of Jumna’s husband. When Jumna came in to work, and went into the kitchen to pick up the jhadu, Nirmalya would say to her: ‘See what happened to these bewdas.’ ‘Every evening he goes and drinks bewda,’ she said, shaking her head, staring at the floor, jhadu in hand. Nirmalya, who’d never seen her husband, pictured him sitting inside a roofed place with tables and an electric light, with men like him who, in this image that flashed upon Nirmalya, had nothing in particular on their minds. When he tried to imagine the liquor that killed these men, gradually or suddenly, it was golden or transparent, like the alcohol he’d noticed being poured out in parties. Then one day he realised it was milky white, like toilet cleaner.

So Jumna’s husband came to inhabit Nirmalya’s life, a malevolent visitor, unredeemable, present but never there. He never saw him.

One cheerful, company-sponsored morning, the husband came to the flat in La Terrasse. Only a few months ago, Jumna had related how she’d woken up in the middle of the night to find herself soaked: her husband, utterly drunk, had drenched her with kerosene, and was trying with little success to light a match, muttering ‘Saala! Saala!’ in the darkness. Now this man was here in La Terrasse, ensconced in the servants’ quarters at the back. Everyone in the house was transformed, as at the advent of a difficult bridegroom; no one, the servants or the Senguptas, knew whether to smile or to be outraged. Jumna had a smile on her lips; you couldn’t tell what it denoted — embarrassment, sadness, a strange affection. The man had broken his leg; he’d come to borrow some money.

Nirmalya, twelve years old, was away in school; he narrowly missed seeing him. He desperately wanted to know what Jumna’s husband looked like.

‘He’s quite sober-looking,’ Mallika Sengupta said. She used the word ‘sober’ to mean ‘serious’. ‘A very quiet man.’

This was the figure of joy in Mrs Sengupta’s and Nirmalya’s lives, this woman, more than a decade in their employ, whose own life was like a frayed fabric. Mrs Sengupta still sought her out when she had a nagging doubt, an anxiety.

Jumna mimicked the other servants wonderfully: she exactly caught their turns of phrase, their vanity, recreated effortlessly Arthur’s frequent curious glances at the mirror. The kitchen and its dramas came alive in her stories. They sat and listened to her and laughed loudly.

Even her tales of hardship seemed intended to seep into their secure, company-engendered lives with a tinge of sadness they would not otherwise have.

This woman who had nothing — they were oddly obliged to her.

* * *

THE FAMILY PLANNING programme had failed Jumna: she had five children. Her husband had not used Nirodh: Nirodh, which was advertised everywhere like a health warning or a royal edict, in cinema halls and on billboards. When he was small, Nirmalya used to upbraid her for adding to India’s population, to the number with several zeros he’d memorised in school, each zero the sum-total of fate for almost all the people that number comprised; this, he was certain, like her ignorance of the alphabet and of the facts about the universe he was daily introduced to, was a source of her sorrows.

‘Kya karu, baba?’ she said, as he sermonised intently. ‘What can I do?’ The matter was, mysteriously, out of her hands.

What was Nirodh? Was it a sort of mixture, or medicine? Was it available in bottles or packets? How exactly did it perform its curtailing purpose?

Jumna went to a government hospital and had a tubec-tomy; she vanished from work that day. ‘What could I do,’ she said. ‘ He would never stop.’ Mrs Sengupta smiled, relieved. ‘You’ve taken the right decision, Jumna,’ she said, congratulating Jumna for making a shrewd investment.

‘But why did she have so many children?’ Nirmalya enquired of the driver. This driver, George, a dashing Tamil Christian, had a drink problem, he had come back to work from lunch, drunk, declaimed to everybody present in the flat, hectored the other servants about their employer, taken off his white shirt with epaulettes — known, in conjunction with his trousers, as the ‘driver’s uniform’, a striking ensemble — he’d impatiently divested himself, after his speech, of one half of the uniform and fallen into a deep sleep in the servants’ quarters. Later, sober and attempting to shore up his shattered dignity, he’d listened to a description of his behaviour from Apurva Sengupta with a mixture of disbelief and contrition. He also had an eye for women; when driving, he had a habit of speeding up the car brusquely, becoming abruptly focussed, whenever women were crossing, and braking in front of them with a jerk in the nick of time. To Nirmalya’s surprise, the women seemed to enjoy the thrust of the car; once they’d recovered from their startlement, they’d smile in complicity at this mockery of their unassailability.

‘She too must want it,’ said George with a lopsided grin.

Usko bhi mangta hai, were his words.

The idea shocked the boy; Jumna, who could never be rich or happy in this life, and who yet seemed to have transcended desire, the idea that Jumna wanted it .

* * *

‘YOU’R TEACHING Mallika these days.’ Motilalji had brought up the name after several years. Shyamji flinched: at the use of the first name, the air of — not so much disrespect, as the proprietorial casualness with which it was uttered. It was as if he owned her forever, as he did all his students, the new ones as well as the ones who’d shrugged him off like an old set of clothes. Motilalji, eight years ago, had taken Shyamji to Mallika Sengupta: at that time, he used to be her teacher; he had swaggering right of entry into the flat. How quickly that stint had ended, and how long memory was! Mrs Sengupta shuddered when she thought of Motilalji; but she spoke with sad respect of his gift. ‘He used to sing beautifully,’ she said to Shyamji. ‘When he was sober.’

‘Yes, twice a week,’ said Shyamji now, morose and prevaricatory at the observation.

Motilalji had had a stroke a year and a half ago. Part of his face had been paralysed, flesh turned into stone; but it was almost all right now. He was keeping off the drink; sobriety made him taciturn and despondent. Behind him, where he lay supercilious and spent on the divan, knelt the child Krishna; and the smell of his wife’s cooking, mixed with traces of sandalwood incense, hung motionless but elusive in the room.

Shyamji was virtuous in many ways; he had no vice to speak of. People remarked that he didn’t drink; he never smoked. His weakness was sweets; he loved eating jalebis with milk.

When he praised this combination to Mrs Sengupta, she said: ‘Disgusting! You Marwaris and Punjabis have such awful things for sweets. Jalebis with milk. Halwa made from carrots!’

His other weakness was life itself — life and its material reward. Its great material promise. He didn’t want to forgo it.

The idea of withdrawing — into himself, into some temple of art, or some space uncontaminated by the sort of life his richer students led — never occurred to him. Or if it did, it was as a metaphor; something to be admired fervently and solemnly for its truth, while avoided carefully in reality. You couldn’t confuse a fiction, however sacred and beautiful it was, with what life could actually offer you. Because life could be bountiful; he observed, every day around him, its generosity and largesse.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.