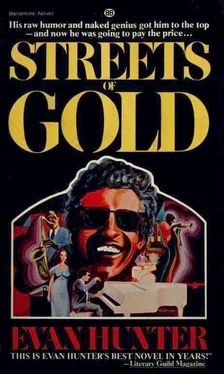

Evan Hunter - Streets of Gold

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Evan Hunter - Streets of Gold» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1975, ISBN: 1975, Издательство: Ballantine Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Streets of Gold

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ballantine Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1975

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-345-24631-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Streets of Gold: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Streets of Gold»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Streets of Gold — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Streets of Gold», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“A calamity!”

“There!”

Pino and Francesco backed into the kitchen on their hands and knees, followed by the iceman and the butcher, all the men clutching wine-drenched towels and sheets and pillowcases, trying to stem the flood of wine as it ran through the rooms, sopping it up, slapping down makeshift dikes. “To your right, Giovanni!” and the iceman threw down his sodden sheet and yelled, “ Got him!” and Teresa shouted, “My linens! Look at my linens!” and Francesco turned over his shoulder and saw the lady from downstairs, and said, “ Buon giorno, signora,” and she answered with her eyes wide and her mouth open, “ Buon giorno,” and Rafaelo the butcher clucked his tongue and said, “What a sin!” and the lady from downstairs said, softly, “It’s dripping on my bed,” and Francesco said, “Get some peaches, and we’ll dip them,” and burst out laughing again. They built a barricade of linens across the kitchen doorway, and finally stopped the flow of wine from the rest of the apartment. Sitting on the floor, dripping purple, laughing as though they had just been through some terrible battle together and had emerged victoriously, they heard Teresa say, “Why don’t you make your wine in the cellar, like other men?”

“What, and pay two dollars?” Francesco said.

Smiling, Teresa said, in Italian, “ Ma sei pazzo, tu.”

“Let’s all have another drink,” Francesco said, and got to his feet. “Pino, I thought you were sotto bossa . Pour us some wine here.” He put his arm around Teresa’s waist. “Would you like a little wine, cara mia? ”

“You’re crazy,” Teresa said, in English this time, but she was still smiling.

And when he was twenty-four (1907?), he came home from the tailor shop late one night, having worked till almost 4 A.M., and found his again-pregnant wife sitting in the kitchen with all the lights on, a bread knife on the table before her. She told him there had been odd knockings at the kitchen door, three knocks in a row, and when she called, “Who’s there?” no one answered, and there was silence. And then, a half hour later, there were three more knocks and again she called, “Who’s there?” and again there was no answer. And then, just before midnight, the same three knocks again, and this time, when she called, “Who’s there?” a voice whispered, “It is I, Regina,” and she knew it was Regina Russo, who had been killed by a horse-drawn cart on 116 Street four years ago before Teresa’s very eyes, and had reached out an imploring hand to Teresa even as the hoofs knocked her down to the cobblestones and the wheels crushed her flat.

Teresa had begun dabbling in the supernatural even before the birth of her second child, a boy she had named Luca in honor of her grandfather, and there were many occasions when Francesco would come home weary and hungry from the tailor shop only to find the neighborhood women clustered around the three-legged table in the kitchen, Teresa solemnly attempting to raise the dead, imploring them to knock once if their answer was yes, twice if it was no, the table wobbling beneath the trembling hands of the women, its legs sometimes banging against the floor in supposed response from the grave. Francesco considered all of this nonsense, and not for a moment did he believe that whoever had knocked on the door was Regina, who was after all dead and gone. But it worried him that Teresa had been alone in the apartment with the three children, and expecting another baby, when someone had knocked on the door and refused to answer. (He dismissed the whispered “It is I, Regina” as a figment of Teresa’s overactive imagination and her preoccupation with things supernatural.)

So he organized a group of men from the building, and each night they would take turns sitting in the hallway on one or another of the floors, and they did this for a week without result until finally on the very next night, when it was Francesco’s turn to guard the building, he saw a man coming up the stairs in the darkness, and he bunched his fists and waited as the man approached the landing. He could smell the odor of whiskey, he realized all at once that the man was stumbling, the man was drunk. He waited. The man approached the toilet set between the two apartments and then very politely knocked on the door of the toilet three times, and when he received no answer, entered and closed the door behind him. Francesco waited. Behind the door, he could hear the man urinating. Then he heard the flush chain being pulled, and the torrent of water spilling from the overhead wooden box. In the darkness, he smiled.

When the man came out, he took him by the elbow and led him down to the street and told him he was not to use the toilets in this building again, they were not public facilities, he was not to go knocking on toilet doors in the middle of the night, did the man understand that? The man was old, wearing only a threadbare suit in a very cold winter, grizzled, lice-infested, stewed to the gills and understanding only a portion of what Francesco said in his faulty English. But he nodded and thanked Francesco for the good advice, and went reeling along First Avenue, and then curled up in the doorway of the Chinese laundry and went to sleep. Teresa survived her pregnancy without any further nocturnal visits from girlhood chums already deceased.

And when he was twenty-four, on most Sundays they visited the home of Umberto, Teresa’s father, the patriarch of the family. They would begin arriving about noon, all of them: Teresa and her husband and the four children; and Teresa’s sister, Bianca, who had not yet begun her corset business, and who was accompanied by her husband, who later ran off to Italy and forced her to fend for herself; and Teresa’s other sister, Victoria, who was as yet unmarried but who was keeping steady company with a man who sold bridles, buggy whips, saddles, harnesses, and reins; and Teresa’s brother, Marco, who sometimes came in from Brooklyn with his wife and three children; and assorted neighborhood compaesani and tailor shop hangers-on, who usually dropped by after la collazione , the afternoon meal, generally served at two o’clock by Teresa’s mother and all her daughters.

That Sunday meal was a feast; there are no other human beings on earth (not even Frenchmen) who can sit down for so long at a table, or eat so much at one sitting. It began with an antipasto — pimentos and anchovies and capers and black olives and green olives in a little oil and garlic — served with crusty white bread Umberto himself cut into long slices from a huge round loaf. While the men at the table were dipping their bread into the oil and garlic left on their antipasto plates, the women were bustling about in the kitchen, taking the big pot of pasta off the stove — spaghetti or linguine or perciatelli or tonellini — straining off the starchy water, and then putting the pasta into a bowl, the bottom of which had been covered with bright red tomato sauce, ladling more sauce onto the slippery, steaming al dente mound, bringing it to the table with an accompanying sauce-boat brimming and hot. “Somebody mix the pasta,” Teresa’s mother would call from the kitchen. And while Umberto himself tossed the spaghetti or macaroni with a pair of forks, and added more sauce to it, the women would bring in more bowls, filled with sausages and meatballs and braciòle , thin slices of beef stuffed with capers and oregano and rolled, and either threaded or held together with toothpicks. And then the women themselves would sit down to join the others, and Umberto would pour the wine for those closest to him, and then pass it to either Francesco or his other son-in-law, or his son Marco, but rarely to the buggy-whip salesman who planned to marry Victoria. There was celery on the table, and more olives, green and black, and there was always a salad of arugala , or chicory and lettuce, or dandelion, which was delicious and bitter and served with a dressing of olive oil and vinegar. And when the pasta course was finished, the women would clear the plates, and the men would pour more wine, and from the kitchen would come platters full of chicken or roast beef or sometimes both, roasted potatoes with gravy, and a vegetable — usually fresh peas or spinach or string beans prepared in the American manner, or zucchini cooked the Neapolitan way — and they would sit and eat this main course while filling each other in on the events of the week and the gossip of the neighborhood, and the latest news from the other side (they almost always referred to it as “the other side,” as though the Atlantic Ocean were a mere puddle separating America from Italy), and then they would rest awhile, and drink some more wine. And then Umberto would go into the kitchen and take from the icebox the pastry he had bought on First Avenue, and usually Teresa’s mother had made a peach or strawberry shortcake with whipped cream, and they would spread the sweets on the table, and only later serve rich black coffee in demitasse cups, a lemon peel in the saucer, a little anisette to pour into the coffee for those who craved it. There would be a bowl of fruit on the table, too, apples and oranges and bananas and, when they were in season, cherries or peaches or plums or sometimes a whole watermelon split in half and sliced, and there would also be a wooden bowl of nuts, filberts and almonds and Brazil nuts and pecans, and hot from the stove would come a tray of roasted chestnuts, marked with crosses on their skins before they were set in the oven, the skins curling outward now to show the browned meat inside — there was much to eat in that decade when my grandfather was twenty-four.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Streets of Gold»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Streets of Gold» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Streets of Gold» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.