The sun was high and beginning to warm the air as they left the bus in Storgata by Ankertorget and caught the one for Bekkensten. Arvid sat on the long seat at the back, and off they went. At Mosseveien Uncle Rolf was waiting at the stop there, he too had a rucksack, the fishing rod was sticking up from one side and Arvid saw him flag down the bus. As he boarded he gave him his broadest smile.

‘Hi, Arvid, you’re up and not crying? That’s good. Today we’re gonna get ourselves a few mackerel.’

‘Sure,’ Arvid said.

The grown-ups sat together to talk about the job they were going to do, the concrete steps on the path down to the jetty were falling apart, so they had to be fixed, and that was the sort of thing Dad liked to busy himself with. He explained to Uncle Rolf how it should be done and Uncle Rolf nodded and looked at Dad and then glanced out of the window at the Oslo Fjord, calm and shining in the autumn sun, and he probably didn’t hear half of it.

Arvid leaned his head back against the rear window and let the vibrations run through his body, tickle his ears, and he closed his eyes and fell asleep.

He was dreaming when his dad stroked his hair and pinched his nose a little to wake him up. He opened his eyes and looked into his dad’s teasing smile. At first he couldn’t tell who he was and he panicked, but then he sighed with relief and smiled and they had reached Bekkensten and had to get out. They left the bus and it turned up the hill towards Svartskog and they began to walk up to the cabin. It was off the road beyond two large gateposts that Dad had set in before the war, the old hinges screaming as they opened the gate and went into the drive past the flagpole.

They were standing at the top of the steps and Dad was about to unlock the door when it just glided open of its own accord and there was no lock at all, the door had been forced and Dad pushed it carefully. Inside the porch there was a mess, one chair was smashed, the table was upside down, and in the living room all the dresser drawers were pulled out and the contents strewn across the floor.

‘Fucking farmers!’ Uncle Rolf shouted and ran round picking things off the floor and dropping them again, and Dad asked what the hell farmers had to do with anything and if he shouldn’t curse the Russians as well, but he was just as angry as Uncle Rolf, Arvid could see by his face, his jaws were so taut he seemed younger than he was. And when they saw that the one who had been there unannounced had done his business in a corner of the living room he started kicking the staircase to the first floor. He kicked and kicked without saying a word, just whacking one foot against the stairs until the paint started to come off in big flakes. Then he stopped and began to clear up without another word. Arvid and Uncle Rolf helped, and after half an hour’s work it didn’t look too bad.

Uncle Rolf made some coffee, and cocoa for Arvid, they took out their packed lunches and sat at the table in the porch eating. Dad had to sit on a stool because the other chair had been smashed into kindling. When they had finished, Dad went out into the shed and found all the things they needed to patch up the steps.

Arvid went to greet the sea, he had his high boots on and he waded in the shallow water picking mussels, there were lots of them, until his fingers were blue. He tried skimming stones across the water instead, but even that didn’t go so well. He blew on his fingers and held them against his stomach under his jumper. His stomach was smooth and firm and warm, and he shuddered as his cold hands met his skin.

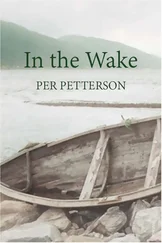

He went back up. The canoe lay on two stands under a spruce tree, and had been there since Granddad died. He ran his finger along the side. The red paint was peeling and when he pressed hard his finger sank into the woodwork. It was a creepy feeling.

Further up the steep hill he heard his dad and Uncle Rolf arguing. Mostly it was his dad’s voice he heard. He was on his knees with a bricklayer’s trowel, Uncle Rolf was standing beside him with a bucket of cement, looking forlorn. Uncle Rolf wasn’t very practical, he preferred to talk. Most of the time this was fine, for Dad loved to work with his hands, but now he was in a bad mood and said:

‘You’re not much use, you never have been. I remember before the war when we were putting up this whole mess, you weren’t much use then either. The old man and I had to do just about everything alone. You always had to be helped. Jesus, I even had to fight your fights at school!’

Uncle Rolf said nothing, and Arvid passed them on the way up to the cabin. He went into the living room and unpacked the fishing tackle from his rucksack, assembled the fishing rod, fixed the line and spinner, put on a warm jacket and went back out. Dad and Uncle Rolf were coming up. Arvid met them on the steps.

‘Where are you going?’ Dad asked.

‘Aren’t we going fishing now?’

Dad looked at his watch. ‘It’s too late. Perhaps we’ll have time tomorrow. We’ll see.’

Arvid turned, went in, dismantled the rod, stuffed the two parts into the bag and put everything back in the rucksack. He took out Huckleberry Finn and sat on the divan and began to read. It was the third time he had read it. It was the finest book ever written and he knew he would read it many more times. He only had to wait a few weeks until the next time, then the desire would return, but now it wasn’t easy to concentrate. He kept looking up at his dad, who had been to the well and fetched a bucket of water. Dad always washed with ice-cold water when he was at the cabin, and he tried to make Arvid do the same, but Arvid turned blue all over and had started to refuse.

‘Cold water toughens you up,’ Dad said. ‘You have to harden yourself, if you don’t want to be a sissy. When I was young, before the war, I always had a shiver bath in the morning. It helped me endure most things.’

Arvid looked at his dad bent over the bucket, he had filled a pitcher and poured the water over the back of his neck, and it ran down his shoulders, and he stood without moving or shivering and Arvid realised that it was true. He could endure most things.

And suddenly he was as gentle as butter again.

‘Would you like something to drink, Arvid?’ he asked, taking a bottle of Asina from his rucksack. Asina was good, it tasted like Solo lemonade, but Asina was cheaper. Dad poured a glass and set the bottle and the glass on the table the way they did in cafés. Another bottle was produced from the rucksack, and Arvid knew what it was, it was aquavit. Dad smacked the bottle down on the table.

‘Now we grown-ups will have ourselves a dram, for this has been one shit day!’ Uncle Rolf fetched two glasses and poured and then they had a shot each and began to talk about the old days, and Arvid sat on the divan reading Huckleberry Finn and drinking Asina. He had come to the part where Huck and Jim are on the shipwrecked boat and run into a gang of robbers and it was exciting, but then he was tired again and had to put the book down and sleep a little.

It was Uncle Rolf’s voice that woke him. He glanced over at the table where there was almost nothing left in the bottle, the paraffin lamp was lit and Uncle Rolf was shouting:

‘You think you’re so damn clever at everything, you and the old man were always like that, but none of us ever made anything of ourselves, we’re just plain workers. And you think you’re so damn tough and strong, but you don’t even use your head, you know nothing, you never understood the old man was a bastard!’

‘Don’t talk like that about my father!’

‘He was my father too, but he was still a bastard! What do you think it was like for me living alone in Vålerenga with that quarrelsome character after you and your wife moved out? But you were the golden boy, weren’t you? You two and the cabin and the damned canoe and all the things the two of you did.’

Читать дальше