The nurse told me you were in an incubator — you were having trouble breathing — but that Esme was awake and asking for me again.

I said I’d be right there. I had flowers delivered from the lobby florist with a note that said: I’m on my way! And then I did something awful. I left. I raced my car through every yellow in town and got back to campus.

Marshall gave me a kiss. And I was so relieved to be there with her. For months I’d been telling Marshall about the Helix. That I wanted to believe in this thing to save me from myself. Maybe to save a few other people, too. She said if I was going to be a leader, I’d have to shore up my pitch and make it coherent. Hone my ideas, communicate in story. She said I talked drivel and didn’t have the charisma to hide it. I was, she said, more Koresh than Jim Jones, though we were agreed I was neither.

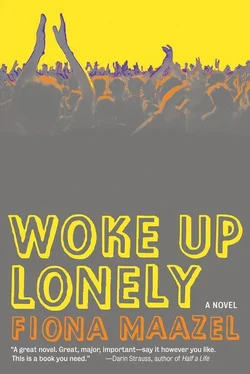

The plaza was full, which was insane for February. There were banners and balloons, torchlights and pizza. I started to panic. It would be hours before the horror of abandoning Esme tided over me so that I could not breathe, which meant the distress of the moment was caused by something else. And it was this: Those hundred people in the audience? Their lives could change for hearing me vaunt ideas I barely understood myself. Did I really think the predicament of being alone was soluble? I’d just left my wife and new baby to start their lives together without me for dread of us never being able reach each other, no matter what we said. So I don’t know. I was afraid. Too afraid to test out the very ideas I was about to insist were a retort to loneliness and despair. And yet there I was. Because maybe one in those hundred applauding my name would be less scared than me.

They introduced me as a social psychologist who lectured nationwide and whose highly anticipated writ on the topic of loneliness would be issued by an eminent and heroic publishing juggernaut in the spring. I glanced at Marshall, who smiled big, and the smile said: In time, these lies will come true, so who cares?

From the dais, I did not recognize anyone. I found out later that my childhood friend Norman was in the aisle, three rows in, but that he didn’t stay for the whole speech, just long enough to make eye contact with me. Or so he thought, because it wasn’t faces I saw but the same face in every one, of my wife, anguished and alone. And so I started talking about her. I said I worried she was as unknown to me as a stranger in the park. I said that the negative space contoured by our absence in each other’s lives gave shape to what was impossible to shape otherwise but which I could now see with a horror I could barely put into words. What does loneliness look like? So long as my wife was out there, this person I adored, clamoring for me and getting no response, I had a good idea.

I said, “But this isn’t about me. It’s about us all. Because everywhere and all the time, people are crying out for each other. Your name. Mine. And when you look back on your life, you’ll see it’s true: woke up lonely, and the missing were on your lips.”

I blinked at the audience, which had been quiet for a while. As I spoke, the antiwar posters had come down like the flag post-death. I’d noticed a few balloons released and bound for paradise. I turned off the mic. The crowd dispersed. I’d say it was funereal except that no one goes into a funeral expecting to be stoked. This was more like the aftermath of a big loss for the home team.

Marshall gave me a hug. I told her that my baby was three hours old and that I had to go. She lifted the hem of her T-shirt, and there was a double helix tattooed on the small of her back.

I rushed to the hospital. This time, Esme had company. I found Norman sitting next to the bed and holding her hand. It was even possible he was trying to explain me. I was stunned but then not, because if Norman was his own season, he came every year.

I gave him the nod and took her other hand. Kissed her on the forehead and said I’d seen the baby, that she was a marvel. I had not seen the baby, but in my head, I knew I was right.

Esme’s voice was quiet, and for a second, I thought all would be well. Then she said, “Where were you, Lo?”

I’d had hours to prepare an answer, but in my will to believe I was not shirking responsibility in the most horrible way, I had refused to accept this moment would come. I looked at Norman. I half expected a miracle to intercede on my behalf. Just give me a minute, let me think.

Her face was blanched; her hair was matted. I spliced my fingers with hers and thought I’d never loved her more.

Norman said, “Esme, it’s like I said before: I’m so sorry. It’s my fault. I talked Lo into leaving work early and taking a drive with me and the car broke down. We just got back. Lo was just paying the cab.”

I nodded, restated, embellished, and finally I just wept. I pressed each of her knuckles to my lips and wept. I had escaped discovery — the relief was palpable — and so I wept for this. Norman had secured for me a chance to redress this terrible mistake, and so I wept for that, too. I wept because I knew I would not redress the mistake and, in fact, would do worse in the months to come. My wife loved me, my daughter would love me long before she knew what this meant, and for these travesties I wept most of all.

It pains me to have to say it, but I will: In the year after you were born, there were other women. Several. People I tried to connect with because I could not connect with you or your mother, though it turns out I couldn’t really connect with them, either. Still, I tried. They all knew I was married. I told them everything. I talked and shared and it helped. At least in the short term. I’d come home less afraid. Less unknown. And, while I knew it was wrong, it also felt right. So I was confused. And depressed. And when it got so bad, and I stopped knowing what to do, Esme made the decision for us. She packed you up and split. She left me to the Helix.

After that? Magical thinking. I’d wake up with hope. Not hope legitimized by a real development for good, not hope born of faith in the world’s benevolence, but hope that is your way of staying alive. I believed you were coming back. Some days, this was okay. Other days, I’d take myself down. What insanity! You’re an idiot! They are not coming back; they are never coming back. The rest of the day might be given over to sobbing in a ball, only the next morning I was up and at ’em, sprightly as before.

It got so quiet in the house, I’d put a fork down the garbage disposal just so I could call a repairman. I clogged the bathtub drain with screws and dimes and a sock, and when the plumber took a break, I undid his good work. But these people never stayed more than an hour.

I quit my job and began skimming a salary from donations to the Helix. We headquartered on campus, but I went everywhere, and at every stop, I asked after my wife. I wanted a miracle. Esme worked for the government; if she wanted to vanish, she would.

I went to therapy all the time. The regret of what I had done was awful, but the permanence was worse. A shrink at SUNY told me I should believe in myself. And I did. I believed I was stupid and evil and without hope. I thought I would not make it. Only time intervened — it always does — and with it came the prize and mercy of endurance. In lieu of facts, I had possibility. Since you could be anywhere, I began to see you everywhere. My little girl, in saddle shoes and party dress.

Esme left most of your stuff behind, so I have your baby socks in a drawer by my bed. But these are just artifacts, and as the years go by, they have become less solace than rebuke. One time I had your baby photo age-progressed, then made the mistake of doing it again elsewhere, and when the results were girls who barely resembled each other, I postered my wall with their likenesses.

Читать дальше