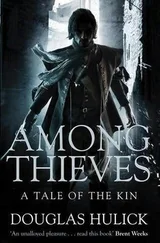

the days were long and silent — Bassam followed his ritual, without saying anything, he was waiting, waiting for a sign or for the end of the world, just as I was waiting for Judit’s operation, which looked as though it was going to be longer and more difficult than foreseen; in the evening I’d go out for a walk with Mounir in Barcelona’s warm humidity, which was like Tangier or Tunis — relieved, we’d leave Bassam on the Street of Thieves to go to our little sidewalk café a little farther south, on Calle del Cid; we’d drink some beers there, nicely tucked away in that forgotten lane, and Mounir was a great comfort, he’d always end up cracking me up: despite his fragile situation, he kept his sense of humor, his energy, and he managed to communicate some of it to me, make me forget everything I’d lost, everything that had broken, despite the world around us; Spain, sinking into crisis, Europe, destroying itself before our eyes, and the Arab world, not escaping from its contradictions. Mounir had been relieved by the victory of the Left in the French presidential elections, he saw hope in it, he was optimistic, nothing for it, him the small-time thief, the dealer, he thought the Revolution was still underway, that it hadn’t been crushed once and for all by stupidity and blindness, and he laughed, he laughed at the millions of euros swallowed up in the banks or in bankrupt nations, he laughed, he was confident, all these misfortunes were nothing, his poverty in Paris, his misery in Barcelona, he still had the strength of the poor and the revolutionary, he said One day, Lakhdar, one day I’ll be able to live decently in Tunisia, I won’t need Milan, Paris or Barcelona anymore, one day you’ll see, and I who had never really wanted to leave Tangier, who had never really shared these dreams of emigration, I’d reply that we’d always be better off tucked away in the Raval, in our palace of lepers, watching the world collapse,

the days were long and silent — Bassam followed his ritual, without saying anything, he was waiting, waiting for a sign or for the end of the world, just as I was waiting for Judit’s operation, which looked as though it was going to be longer and more difficult than foreseen; in the evening I’d go out for a walk with Mounir in Barcelona’s warm humidity, which was like Tangier or Tunis — relieved, we’d leave Bassam on the Street of Thieves to go to our little sidewalk café a little farther south, on Calle del Cid; we’d drink some beers there, nicely tucked away in that forgotten lane, and Mounir was a great comfort, he’d always end up cracking me up: despite his fragile situation, he kept his sense of humor, his energy, and he managed to communicate some of it to me, make me forget everything I’d lost, everything that had broken, despite the world around us; Spain, sinking into crisis, Europe, destroying itself before our eyes, and the Arab world, not escaping from its contradictions. Mounir had been relieved by the victory of the Left in the French presidential elections, he saw hope in it, he was optimistic, nothing for it, him the small-time thief, the dealer, he thought the Revolution was still underway, that it hadn’t been crushed once and for all by stupidity and blindness, and he laughed, he laughed at the millions of euros swallowed up in the banks or in bankrupt nations, he laughed, he was confident, all these misfortunes were nothing, his poverty in Paris, his misery in Barcelona, he still had the strength of the poor and the revolutionary, he said One day, Lakhdar, one day I’ll be able to live decently in Tunisia, I won’t need Milan, Paris or Barcelona anymore, one day you’ll see, and I who had never really wanted to leave Tangier, who had never really shared these dreams of emigration, I’d reply that we’d always be better off tucked away in the Raval, in our palace of lepers, watching the world collapse,  and that made him laugh.

and that made him laugh.

Iwas increasingly convinced that the Hour was near; that Bassam was waiting for a signal to play his part in the end of the world — he would disappear for much of the day, during prayer times; he pretended to be happy when I suggested we go out for a bit, change neighborhoods, enjoy the city that held its arms out to us; he managed to pretend for half an hour, to go into raptures over one or two girls and three shop windows, then he’d become silent again, snapped up by his memories, his plans, or his hatred. When I grilled him he’d look at me with his simpleton’s face, his eyes incredulous, as if he didn’t have the slightest clue as to what I was talking about, and I began to doubt, I told myself I was exaggerating, that the ambiance, the Street of Thieves, and Judit’s illness were beginning to get to me, so I’d promise myself not to mention it to him again — until night came, when he’d disappear for two or three hours, God knows where, in the company of his random Pakistani pals and he’d return, silent, with the lost, tremulous gaze of someone wanting to ask a question, taking Mounir’s place on the sofa, and my doubts and questions would reappear. One day I noticed that he had come back with a plastic bag, bizarre for someone who never bought himself anything, who owned almost nothing, aside from a few pieces of clothing which he ritually washed by hand every night before bed — I glanced into it when he went to piss; the package contained four new cellphones of a very simple model, I remembered the modus operandi of the Marrakesh attack, of course I couldn’t resist, I asked him the question, he didn’t seem angry that I’d searched through his things, just a little tired of my suspicions, he answered very simply it’s a little business with my pals from down there, if you like I can get you one free of charge — the naturalness of his answer disarmed me, and I fell silent.

I was probably going mad, completely paranoid.

ONEday I couldn’t stand it anymore, I talked about it with Judit. She was still in the hospital, the operation kept being delayed: major budget cuts had forced the hospital to close a wing of its operating theaters — and there were always more urgent cases to be operated on.

Núria wasn’t there, we were alone in her room; she was sitting in the visitor’s chair, and I was on the floor next to her. I hesitated for a long time, and I said to her, you know, I wonder if Bassam is preparing for something.

She leaned toward me.

“Something dangerous, you mean?”

“Yes, something like Marrakesh or Tangier. But I’m not sure. It’s just a possibility.”

I thought of Bassam’s new gaze, so empty, so lost, so suffering.

Judit sighed, and we stayed silent like that for a while.

“And what’re you going to do?”

“I don’t know.”

She leaned over to stroke my forehead, and then she sat down next to me, on the floor, her back leaning against the bed, she held me tight and we embraced for a long time.

“Don’t worry, I know you’ll make the right decision.”

In the end she had to gently dismiss me so I’d go back to the Street of Thieves, leaving behind me the horde of intubated smokers on the hospital’s plaza.

WHETHERit was dereliction or violence, it doesn’t matter. Bassam circled, eaten away by a leprocy of the soul, a disease of despair, abandoned — what could he have seen over there in the East, what had happened, what horror had destroyed him, I haven’t a clue; was it the sword attack in Tangier, the dead in Marrakesh, the fighting, the summary executions in the Afghan underground, or none of the above, nothing but solitude and the silence of God, that absence of a master that drives dogs crazy — I felt as if he were appealing to me, asking me something, as if his eyes were seeking me out, as if he wanted me to cure him, as if the end of the world had to be stopped, as if the flames had to be stopped from rising and invading everything, and Bassam was one of those birds of the apocalypse who keep circling, just as Cruz watched violent death videos online all day, and I was sure of nothing, nothing aside from that summons, that force of violence — that question that Cruz asked as he swallowed his poison in front of me, deciding to end it all in the most horrible way, I thought I saw it again in Bassam’s eyes. That will to end it all. Sometimes you have to act, when the flames flare up too high, too pressing; I watched Bassam return from the mosque after prayer, say a few words, hello Lakhdar my brother, throw himself on the sofa — Mounir had locked himself in his room; I’d exchange a few banalities with Bassam before taking refuge in my cubbyhole and watch the circus of the Street of Thieves for hours on end, all those people going round in circles in the night.

HISeyes were closed.

I stroked his rough skull, I thought of Tangier, of the Strait, of the Propagation for Koranic Thought, of the Café Hafa, of girls, the sea, I saw Tangier again streaming in the rain, in the fall, in the spring; I pictured us walking, pacing up and down the city, from the cliffs to the beach; I went over our childhood, our adolescence, we hadn’t lived very long.

Mounir came out of his room two hours later, saw the body, then looked at his bloodied knife on the floor, horrified; he shouted but I didn’t hear him; I saw him gesticulating, panicked; he quickly gathered up his things, I saw his lips moving, he said something that I didn’t understand and took to his heels.

I fell asleep, on the sofa, next to the corpse.

In the afternoon I called the cops from my cellphone. I gave the address almost smiling, 13 Street of Thieves, fourth on the left.

Читать дальше

the days were long and silent — Bassam followed his ritual, without saying anything, he was waiting, waiting for a sign or for the end of the world, just as I was waiting for Judit’s operation, which looked as though it was going to be longer and more difficult than foreseen; in the evening I’d go out for a walk with Mounir in Barcelona’s warm humidity, which was like Tangier or Tunis — relieved, we’d leave Bassam on the Street of Thieves to go to our little sidewalk café a little farther south, on Calle del Cid; we’d drink some beers there, nicely tucked away in that forgotten lane, and Mounir was a great comfort, he’d always end up cracking me up: despite his fragile situation, he kept his sense of humor, his energy, and he managed to communicate some of it to me, make me forget everything I’d lost, everything that had broken, despite the world around us; Spain, sinking into crisis, Europe, destroying itself before our eyes, and the Arab world, not escaping from its contradictions. Mounir had been relieved by the victory of the Left in the French presidential elections, he saw hope in it, he was optimistic, nothing for it, him the small-time thief, the dealer, he thought the Revolution was still underway, that it hadn’t been crushed once and for all by stupidity and blindness, and he laughed, he laughed at the millions of euros swallowed up in the banks or in bankrupt nations, he laughed, he was confident, all these misfortunes were nothing, his poverty in Paris, his misery in Barcelona, he still had the strength of the poor and the revolutionary, he said One day, Lakhdar, one day I’ll be able to live decently in Tunisia, I won’t need Milan, Paris or Barcelona anymore, one day you’ll see, and I who had never really wanted to leave Tangier, who had never really shared these dreams of emigration, I’d reply that we’d always be better off tucked away in the Raval, in our palace of lepers, watching the world collapse,

the days were long and silent — Bassam followed his ritual, without saying anything, he was waiting, waiting for a sign or for the end of the world, just as I was waiting for Judit’s operation, which looked as though it was going to be longer and more difficult than foreseen; in the evening I’d go out for a walk with Mounir in Barcelona’s warm humidity, which was like Tangier or Tunis — relieved, we’d leave Bassam on the Street of Thieves to go to our little sidewalk café a little farther south, on Calle del Cid; we’d drink some beers there, nicely tucked away in that forgotten lane, and Mounir was a great comfort, he’d always end up cracking me up: despite his fragile situation, he kept his sense of humor, his energy, and he managed to communicate some of it to me, make me forget everything I’d lost, everything that had broken, despite the world around us; Spain, sinking into crisis, Europe, destroying itself before our eyes, and the Arab world, not escaping from its contradictions. Mounir had been relieved by the victory of the Left in the French presidential elections, he saw hope in it, he was optimistic, nothing for it, him the small-time thief, the dealer, he thought the Revolution was still underway, that it hadn’t been crushed once and for all by stupidity and blindness, and he laughed, he laughed at the millions of euros swallowed up in the banks or in bankrupt nations, he laughed, he was confident, all these misfortunes were nothing, his poverty in Paris, his misery in Barcelona, he still had the strength of the poor and the revolutionary, he said One day, Lakhdar, one day I’ll be able to live decently in Tunisia, I won’t need Milan, Paris or Barcelona anymore, one day you’ll see, and I who had never really wanted to leave Tangier, who had never really shared these dreams of emigration, I’d reply that we’d always be better off tucked away in the Raval, in our palace of lepers, watching the world collapse,  and that made him laugh.

and that made him laugh.