ITwas Sheikh Nureddin who warned me, via a brief email; life is a funny thing, a mysterious arrangement, a merciless logic of a futile destiny. He was coming to visit me. He had to pass through Barcelona for a meeting, on business. I confess I was happy to see him again, a little worried, too — the echo of the Marrakesh attack still hovered, a year later. The fire at the Group for Propagation of Koranic Thought, too. Questions that I had turned over in my mind for so long — little by little they had emptied themselves of meaning.

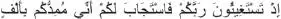

Sheikh Nureddin was powerful — he disappeared whenever he pleased and reappeared whenever he thought fit, from Arabia or Qatar, the non-combatant branch of a pious foundation, without any passport, visa, or money problems. Always elegant, in a suit, with a white shirt, no tie of course, a short well-trimmed beard, a little black briefcase; he spoke calmly, smiled, even laughed sometimes; his voice could glide from the gentleness of brotherhood to the shouts of battle, I can still hear them sometimes in my sleep, those speeches on the battle of Badr, I will come to your aid, with a thousand angels following each other,

it seemed as if he knew the entire Koran by heart,

it seemed as if he knew the entire Koran by heart,  God gave you victory in Badr when you were at your weakest, and the Text shone forth from his mouth, gleamed with a thousand lights of those angels promised by the Lord; he would spend hours telling us the story of Bilal, the slave tortured for his Faith, who became the first muezzin in Islam and whose voice, his voice alone, could draw tears from the inhabitants of Medina when he made the call to prayer — all those stories filled us with strength, joy, or anger, depending on their themes.

God gave you victory in Badr when you were at your weakest, and the Text shone forth from his mouth, gleamed with a thousand lights of those angels promised by the Lord; he would spend hours telling us the story of Bilal, the slave tortured for his Faith, who became the first muezzin in Islam and whose voice, his voice alone, could draw tears from the inhabitants of Medina when he made the call to prayer — all those stories filled us with strength, joy, or anger, depending on their themes.

Seeing Sheikh Nureddin again was a Sign: a part of me, of my life, of my childhood reappeared in Barcelona, and despite the doubts, the mysteries, the shame linked to the nocturnal expedition of the bruisers of Tangier, a little light entered the Street of Thieves.

I had told Mounir everything, without mentioning the most worrisome details, and even though he was anything but religious, I managed to transmit a little of Sheikh Nureddin’s energy to him; Mounir was anxious to meet him. I secretly hoped the reason for his trip was to open an office-bookstore in Barcelona I could take charge of, like in Tangier; that would explain why he had gotten back in touch. I pictured a little shop in the Raval, with books in Spanish, in Arabic, why not, in French — a miracle. A bookstore whose stock would have been mainly made up of books from Arabia, but with one or two shelves of thrillers and a shelf in homage to Casanova — a place, in short, that would somewhat resemble me. Yes of course, I was an illegal and a fugitive, but in my dreams I saw myself registering this little business in Judit’s name and staying there, for years, in that special scent — ink, dust, old thoughts — of books, confident in the knowledge that the boys in blue are not much interested in the written word and, in general, leave bookstores pretty much alone, just as here, today, I’m hardly bothered at all in my library: it’s the only zone of freedom around here, where sometimes even the screws come to chew the fat. Few readers, a lot of books. Of course our joint is far from being one of the largest jails in Spain, but it’s undoubtedly one of the most modern; around me the dogs are strolling down the hallways.

Life is a tomb, it’s the Street of Thieves, the end of the line, a promise without content, empty words.

Sheikh Nureddin’s arrival coincided with the diagnosis of Judit’s tumor. The doctor suspected that allergies, sinusitis, or God knows what depression could be the symptoms of a more serious disorder; her parents had paid for the MRI out of their own pockets to avoid the state health care system delays and the results were back; something was growing on the side of her brain. They still had to wait to find out if this “thing” was treatable, operable, malignant, benign, if there was any hope or if her prognosis as the docs say was very poor —I took the news like a physical blow. Judit told me gently, though, as if she were more worried about me than about herself, an effect of the illness perhaps. Her mother could barely hold back her tears, her eyes seemed to be constantly shimmering. Judit, lying on the sofa, gently took my hand, and I wanted to bawl too, to shout, to pray, I thought ya Rabb, don’t take Judit away to death, please, you can’t take all the women I’ve loved, I thought of Meryem again, maybe I was the one who was transmitting the malady of death to them, have pity, Lord, let Judit live, I’d have easily traded my shitty existence for her life, but I knew my offer was good for nothing.

On my way back I stopped to use the Internet, I looked at dozens of pages on brain tumors, there were all kinds, terrifying descriptions of the evolution of symptoms in certain cases, great stories of cures in others, I said to myself it’s impossible, Judit is twenty-three, according to this statistic serious cancers are very rare at that age, that’s definite, it’s all just a false alarm, and I was so caught up by this macabre wandering through descriptions of the nooks and crannies of death that I arrived late to my meeting with Nureddin, near Plaça de Catalunya, out of breath, tense, sad, and worried.

The Sheikh hadn’t changed, he was sitting at a table on the terrace in front of a café, looking noble and well-dressed; a young guy was with him, with a shaved head and a black beard; he got up as I approached and threw himself into my arms: Bassam, Bassam good Lord, I was overcome with joy, Bassam, wow, Bassam, he said Lakhdar my brother, clutched me to his chest and for a little while I forgot to greet Nureddin who laughed at the warmth of our reunion, I said Bassam my friend, even your mother wouldn’t recognize you, he replied and you with your white hair, you look like you’ve become a miller. It does me good to see you, thanks be to God.

Full of emotion, I also embraced the Sheikh — and right away we no longer knew what to say, where to begin. Bassam was sitting down again, he had stopped smiling; he had the disturbing gaze of a blind man or certain animals with frightened, fragile eyes which always seem to be staring off into the distance. Sheikh Nureddin began questioning me about my life in Barcelona; he wanted to know how I had arrived here. I told them a little of my adventures; of course I hid the end of the Cruz episode from them. When I mentioned the fire at the Propagation for Koranic Thought, the Sheikh nodded with a look of disgust: the cowardly revenge of an impious one, a bastard who took advantage of our absence to attack the Book itself, what dishonor. He said this point-blank, with accents of rage in his voice — I suddenly remembered the bookseller, his mute surprise when he had seen me entering his store; maybe he had taken revenge. It was possible. Life is nothing but a series of wrong answers and misunderstandings.

Bassam continued to be silent; he swayed his head from time to time, stared at passersby, looked at girls’ legs, his eyes always just as empty.

I had a slew of questions for Bassam and Nureddin — I dared to ask the first, what had happened, why had they disappeared all of a sudden? The Sheikh looked surprised, but you were the one who was no longer there, son. When we came back from that meeting in Casablanca, I discovered our headquarters had burned down — you hadn’t left an address. We even suspected you for a while. Then I learned through Bassam (who shook himself a little when he heard his name, as if he were waking up) that you had a relationship with a young Spanish woman and you had left without leaving a trace. This in a reproachful tone, before adding but that’s ancient history, we forgave you.

Читать дальше

it seemed as if he knew the entire Koran by heart,

it seemed as if he knew the entire Koran by heart,  God gave you victory in Badr when you were at your weakest, and the Text shone forth from his mouth, gleamed with a thousand lights of those angels promised by the Lord; he would spend hours telling us the story of Bilal, the slave tortured for his Faith, who became the first muezzin in Islam and whose voice, his voice alone, could draw tears from the inhabitants of Medina when he made the call to prayer — all those stories filled us with strength, joy, or anger, depending on their themes.

God gave you victory in Badr when you were at your weakest, and the Text shone forth from his mouth, gleamed with a thousand lights of those angels promised by the Lord; he would spend hours telling us the story of Bilal, the slave tortured for his Faith, who became the first muezzin in Islam and whose voice, his voice alone, could draw tears from the inhabitants of Medina when he made the call to prayer — all those stories filled us with strength, joy, or anger, depending on their themes.