Vikram Seth - A Suitable Boy

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Vikram Seth - A Suitable Boy» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Orion Publishing Co, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Suitable Boy

- Автор:

- Издательство:Orion Publishing Co

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Suitable Boy: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Suitable Boy»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Suitable Boy — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Suitable Boy», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

With a start Mr Justice Chatterji realized that he himself did not think very often of his wife. They had met at one of those — what were they called, those special festivals for young people held by the Brahmo Samaj, where teenagers and so on could get to meet? — Jubok Juboti Dibosh. His father had approved of her, and they had got married. They got on well; the house ran well; the children, eccentric though they were, were not bad as children went. He spent the earlier part of his evenings at the club. She very rarely complained about this; in fact, he suspected that she did not mind having the early evening to herself and the children.

She was there in his life, and had been there for thirty years. He would doubtless miss her if she wasn’t. But he spent more time thinking about his children — especially Amit and Kakoli, both of whom worried him — than about her. And this was probably true of her as well. Their conversations, including the recent one that had resulted in his ultimatum to Amit and Dipankar, were largely child-bound: ‘Kuku’s on the phone the whole time, and I never know who she’s speaking with. And now she’s taken to going out at odd hours, and evading my questions.’ ‘Oh, let her be. She knows what she’s doing.’ ‘Well, you know what happened to the Lahiri girl.’ And so it would start. His wife was on the committee of a school for the poor and was involved in other social causes dear to women, but most of her aspirations centred on her children’s welfare. That they should be married and well settled was what, above all, she desired.

She had been greatly upset at first by Meenakshi’s marriage to Arun Mehra. Predictably enough, once Aparna was born she had come around. But Mr Justice Chatterji himself, though he had behaved with grace and decency in the matter, had felt increasingly rather than decreasingly uneasy about the marriage. For a start, there was Arun’s mother, who was, in his mind, a peculiar woman — overly sentimental and liable to make much of nothing. (He had thought that she was not a worrier, but Meenakshi had filled him in with her version of the matter of the medals.) And there was Meenakshi, who sometimes displayed glints of a cold selfishness that even as a father he could not completely blind himself to; he missed her, but their breakfast parliaments, when she lived at home, had been more seriously acrimonious than they now were.

Finally, there was Arun himself. Mr Justice Chatterji respected his drive and his intelligence, but not much else. He seemed to him to be a needlessly aggressive man and a rank snob. They met at the Calcutta Club from time to time, but never found anything much to say. Each moved in his separate cluster at the club, clusters suited to their difference of age and profession. Arun’s crowd struck him as gratuitously boisterous, slightly unbefitting the palms and the panelling. But perhaps this was just the intolerance of age, thought Mr Justice Chatterji. The times were changing beneath him, and he was reacting exactly as everyone — king, princess, maidservant — had reacted to the same situation.

But who would have thought that things would have changed as much and as swiftly as they had. Less than ten years ago Hitler had England by the throat, Japan had bombed Pearl Harbour, Gandhi was fasting in jail while Churchill was inquiring impatiently why he was not yet dead, and Tagore had just died. Amit was involved in student politics and in danger of being jailed by the British. Tapan was three and had almost died of nephritis. But in the High Court things were going well. His work as a barrister became increasingly interesting as he grappled with cases based on the War Profits Act and the Excess Income Act. His acuity was undiminished and Biswas Babu’s excellent filing system kept his absent-mindedness in check.

In the first year after Independence he had been offered judgeship, something that had delighted his father and his clerk even more than himself. Though Biswas Babu knew that he himself would have to find a new position, his pride in the family and his sense of the lineal fitness of things had made him relish the fact that his employer would now be followed around, as his father before him had been, by a turbaned servitor in red, white and gold livery. What he had regretted was that Amit Babu was not immediately ready to step into his father’s practice; but surely, he had thought, that would not be more than a couple of years away.

7.37

The bench that Mr Justice Chatterji had joined, however, was very different from the one he had imagined — even a few years earlier — that he might be appointed to. He got up from his large mahogany desk and went to the shelf that held the more recent volumes of the All India Reporter in their bindings of buff, red, black and gold. He took down two volumes— Calcutta 1947 and Calcutta 1948— and began comparing the first pages of each. As he compared them he felt a great sadness for what had happened to the country he had known since childhood, and indeed to his own circle of friends, especially those who were English and those who were Muslim.

For no apparent reason he suddenly thought of an extremely unsociable English doctor, a friend of his, who (like him) would escape from parties given in his own house. He would claim a sudden emergency — perhaps a dying patient — and disappear. He would then go to the Bengal Club, where he would sit on a high chair and drink as many whiskies as he could. The doctor’s wife, who threw these huge parties, was fairly eccentric herself. She would go around on a bicycle with a large hat, from under which she could see everything that went on in the world without — or so she imagined — being recognized. It was said of her that she once arrived for dinner at Firpo’s with some black lace underwear thrown around her shoulders. Apparently, vague as she was, she had thought it was a stole.

Mr Justice Chatterji could not help smiling, but the smile disappeared as he looked at the two pages he had opened for comparison. In microcosm those two pages reflected the passage of an empire and the birth of two countries from the idea — tragic and ignorant — that people of different religions could not live peaceably together in one.

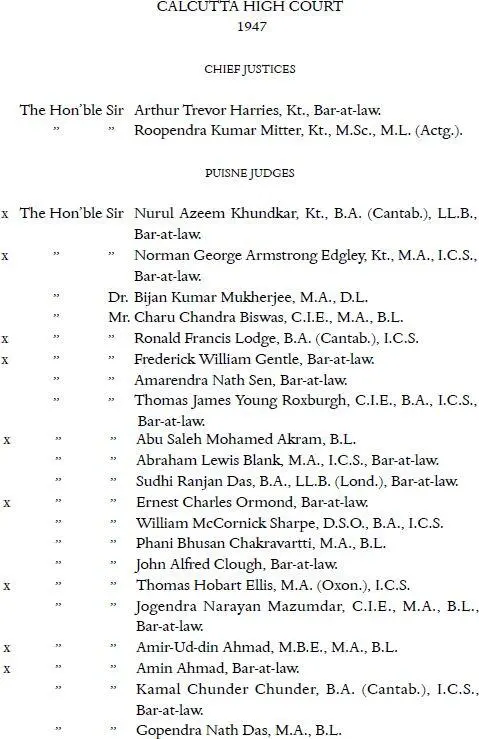

With the red pencil that he used for notations in his law-books, Mr Justice Chatterji marked a small ‘x’ against those names in the 1947 volume that did not appear in 1948, just one year later. This is what the list looked like when he had done:

There were a few more names at the bottom of the 1948 list, his own included. But half the English judges and all the Muslim judges had gone. There was not a single Muslim judge in the Calcutta High Court in 1948.

For a man who in his friendships and acquaintance looked upon religion and nationality as both significant and irrelevant, the changing composition of the High Court was a cause for sadness. Soon, of course, the British ranks were further depleted. Now only Trevor Harries (still the Chief Justice) and Roxburgh remained.

The appointment of judges had always been a matter of the greatest importance for the British, and indeed (except for a few scandals such as in the Lahore High Court in the forties) the administration of justice under the British had been honest and fairly swift. (Needless to say, there were plenty of repressive laws, but that was a different, if related, matter.) The Chief Justice would sound a man out directly or indirectly if he felt that he was a fit candidate for the bench, and if he indicated that he was interested, would propose his name to the government.

Occasionally, political objections were raised by the government, but in general a political man would not be sounded out in the first place, nor — if he were sounded out by the Chief Justice — would he be keen to accept. He would not want to be stifled in the expression of his views. Besides, if another Quit India agitation came along, he might have to pass a number of judgements that to his own mind would be unconscionable. Sarat Bose, for instance, would not have been offered judgeship by the British, nor would he have accepted if he had been.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Suitable Boy»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Suitable Boy» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Suitable Boy» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.