Back in the town square, a team of engineers examined the damage done. The snake was so wide that the front façades of some of the buildings were thoroughly crushed. The creature had become load bearing where it was wedged under the schoolhouse’s roof and against the bank’s pillars, preventing their collapse. As long as the snake didn’t move, the structural damage was not the type that threatened either building’s integrity. One engineer patted the reptilian flank and remarked that the poor girl was stuck. Nobody questioned his determination of sex, as the engineers were perceived as simultaneously knowing everything and nothing at all.

Time passed, and the people grew bold. No apparent clues arose in the mystery of how the snake had come to be, or where, or why; as generations before had found, there was little utility to questioning the unknown. Children made one flank into a climbing wall by leaning boards against its body. Down the way, they used their bikes to section off a court for their handball games. The mothers stood by nervously, but when no harm came to their babies, they went on with their daily work.

Even Swale found herself more interested in the physical presence of the animal than in its origin. As with any bridgeless river, it was difficult to traverse the snake, and so the town was split in two. People started referring to landmarks and locations in terms of the new barrier; the school, church, and nicer homes were in North Snake, while the bank, movie theater, and poorer homes fell within South Snake. Children in South Snake couldn’t get to school anymore, and instead played handball games all afternoon. The children formed rowdy gangs and roamed the area, knocking down mailboxes. In North Snake, people started spending more and more time in the church, until a group of a dozen or so individuals held a constant vigil there, praying all day and night at turns for the health of the snake and for the death of the snake.

A devastating insomnia settled over both sides. The snake’s presence had thrown off the whole town’s biological rhythm. People stayed up late, watching from their porches. They took shifts and acclimated to fewer hours of sleep. Nobody wanted to turn away in the event that it might continue its silent progress, or — God forbid — eat a child, though the snake hadn’t budged in months and one had to travel into the orchard to even see its fangs. Still, nobody wanted to wake and find they had missed any major event, and so they slept less and less. Soon enough, everyone could stay awake for weeks at a time. Schoolteachers rubbed their eyes as the children before them multiplied and vanished, turned sepia-toned, and spoke in tongues. Butchers forgot to log deliveries and had to throw out pounds of spoiled meat.

Swale, who lived in a small apartment in South Snake, observed the darkening circles under the eyes of her neighbors. She suffered a very bad haircut from a woman who paused during the experience to lean against the wall and weep. Watching the woman slide down the wall, Swale realized there was a need. Though she was born and raised to research and she made quite a good scientist, she also aspired to invent and produce a product. Her mother had inspired this dream when she made the very good point that since Swale was unemployed with neither prospects nor money, she would soon have to move back in with her parents — and she didn’t want that, did she? She did not. And so, one afternoon, she brought her kit to the snake.

Children played handball around her as she worked. First, she took a rubbing of the scales and examined their feathery tips on a page of contact paper. She pressed a sponge into its side to see if a liquid might emerge, and then swabbed the area with a moistened cotton ball. Neither technique successfully disclosed any material, and she tapped the snake’s side with her fingertips, considering it. She went to her kit and returned with a fine razor.

Working slowly, she shaved off the tip of a single scale. The reptilian wall shifted with discomfort while she made her incision but calmed once she applied pressure. She examined the sample — a silvery aqueous thing — and used an even finer razor to cut a slight piece, as thin as an eyelash. A gentle titration of the slice in a saline solution caused the material to change slightly, producing a blue glow that matched her calculations. She added another shaved piece to find the solution glowed even brighter, a pinpoint of light in the waning day. The vial’s contents produced a gas, popping out the cork. It glowed with an organic heat. She detected the slight odor of cloves. This was precisely what she had anticipated. Like any good inventor, Swale tried the potion on herself, downing it in one go. It tasted like a rubber ball. She held two fingers to her lips, burped, and slipped to the ground, unconscious.

She woke surrounded by curious townspeople, the night sky at their backs. Her head had been propped up awkwardly against the snake. She rubbed her neck and patted the ground for her pocketwatch. Six hours had passed. And there it was: a sleeping potion to rival any drug, easily administered and instantly effective. And what was truly interesting, she saw once she stood to examine it, was that the snake’s scale had completed its regeneration process. It was impossible to find the spot where she had taken her sample.

The potion worked so efficiently that each individual required only one glowing drop. Folks quickly learned that they should be in bed at the time of dosage, as its immediate effect had them wreaking accidental havoc, smashing into stacks of books and pulling down tablecloths. One woman woke to find herself wrapped up in a load of wet laundry she had tried to hang before the drug kicked in. A man banged his forehead on the side of his drafting desk on the way down and gave his wife quite the scare.

People put in bulk orders. A half-drop formulation worked with children and a double drop treated the obese. The streets cleared out at night. Someone tossed a small package of the drug over to North Snake with usage instructions. Eight hours later, a baseball wrapped in cash came back with a note reading MORE OF IT.

A new empire rested in Swale’s hands. She hired a pair of assistants, taking only a pin drop of her own treatment and waking a few hours later to get back to work. She shaved thicker pieces from the snake. Her young assistants mixed the solution and marked their observations. Swale stood at the sentient wall with her hands on her hips, regarding her vast potential fortune. For all she knew, the snake didn’t mind the knife. The faster they cut, the faster the scales regenerated.

There, in the heat of production, wary Swale heeded the kind of impulse she typically wouldn’t follow. It was a caprice inspired by growing demand, distinguished only by its thrilling mixture of success and greed. In that wild moment, she pushed one of the assistants aside and plunged her surgical steel deep into the snake’s flesh. The blade sunk as if being pulled by a new gravity and then was sucked from her grasp. She found herself elbow-deep in the snake before she thought to draw back.

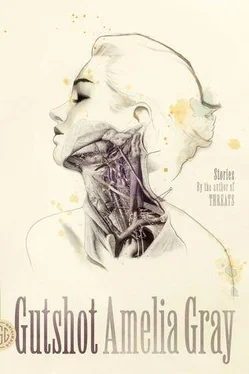

A cracked line of light crowded from the wound, and with it a suffusion of warmth. Swale stared as the snakeskin parted and smoked, peeling back to reveal that the flesh inside formed a cavern. She saw a lantern swinging gently from the knobby spine ceiling. A man sat at a table, regarding her, as calm as the moon. The man turned Swale’s surgical steel in his hand. He resembled a laborer of some type, perhaps a farmer. His long trousers were dark and he was barefoot. An old cap drooped around his eyes, which squinted at the intrusion.

“Hullo there,” the man said. “Please, come in.”

Swale stooped as she entered the cavern. Behind her, the townspeople gathered, each silently convinced that they were experiencing a hallucinatory side effect of the sleeping drug.

Читать дальше