Sam’s illness was like violence. It wasn’t like violence, it was violence. The worst thing in the world.

The news, maybe: ‘… kicking off in Libya and everywhere else down there… They’ve tweeted the News of the World to death… Kicking off in Greece. Portugal next, they reckon, or the Micks, maybe…’

Again the euro crisis: Sam wouldn’t give a toss about the bloody euro crisis. Neil didn’t give a toss about it, either, come to that.

Leila had been ten days old when Sam came to meet her. For a second, while Neil was changing the baby’s nappy, he caught Sam’s face in a mirror: open mouth, crestfallen eyes, which he righted when he saw that he was being watched. He had come to stay with them only a few times since.

Neil hadn’t done what he wanted to do for Sam. He felt remiss, and, worse, he felt irrationally implicated. Here you go , the American girl had said when she gave him her address that morning, as if he had asked for it, which he hadn’t, or might use it, which he never did. Perhaps it would have been better if they had called the police, and Neil had taken his chances in — he groped for the prison’s name — San Somewhere.

Hocus-pocus. Ridiculous.

What was left? Song lyrics: the last refuge of the bedside desperado. You were working as a waitress in a cocktail bar, When I first met you… In the jungle, the quiet jungle, the lion sleeps tonight… Well I’m runnin’ down the road tryin’ to loosen my load.

Sam flinched.

A flinch as in, It’s okay, I know you’re trying ? Or, on the contrary, a Knock it off, will you, for fuck’s sake? sort of flinch? Because, when you stopped to think about it, what was Neil really saying in all his talk? You are ill… You are very very ill… You are ill and I am scared. Nobody wanted to listen to that. Probably his chatter made only one of them feel better.

He shut up. He noticed a little crescent of zits above the corner of Sam’s mouth, an adolescent affliction that seemed touchingly banal in the circumstances. When he was Sam’s age, Neil had salacious, anarchistic thoughts about what he would do in this situation. Fuck hookers, punch policemen, egg the Queen. It wasn’t like that at all.

The tempo of beeps from the monitors picked up; he looked around for a white coat but no one rushed in. Just as he was about to leave, Sam opened his eyes again and seemed to blink an acknowledgement. Neil felt the unwonted tears coming and fought them back. He reconsidered, tried to force them out, and felt something glide down his cheek.

You didn’t get to choose when calamity struck. At a minimum, Neil caught himself thinking during the taxi ride from Harley Street, you should get a say in that. All this would be easier if it had come at a different time: easier in the practicalities, at least, if not the emotions. If the disease had held off until Leila was older. If it had developed before his split with Adam. That was a disreputable, egocentric thought, Neil realised; he was ashamed of it.

Sometimes, when he remembered Adam, he would feel a pain in the region of his liver, a sharp ache like the cramp he sometimes got if he drank too much coffee.

He let Roxanna know he was on the way. Theirs was a queer kind of closeness, he thought as he texted. He had seen her with her legs in the stirrups, wailing in her own shit and blood. He had licked her clitoris and tasted her breast milk (sweeter than he anticipated, with a hint of caramel). They were into the mature phase now, the time when the childishness started, struggling for dominion, picking fights, gaming each other, banking favours and concessions as he and Jess once had. Yet for all the proximity he hadn’t yet assimilated basic Roxanna facts — the temperature at which she liked her bath, her allergies, her preferred orders in restaurant chains and coffee shops.

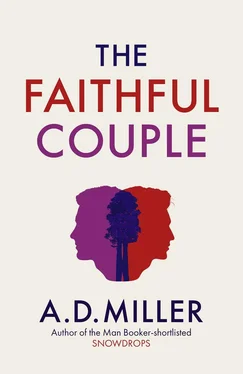

They were obscenely intimate strangers. On rare occasions when Neil’s birth family came up in conversation she would ask polite but desultory questions, as if they were discussing characters from history. Who shot Franz Ferdinand? Who was Henry VIII’s third wife? What colour was Neil’s mother’s hair? To her, his family was dead and buried, and she, Leila and Neil comprised a pristine new reality. She was kind about Sam, but she didn’t see how, for Neil, he was the lone survivor, whom he had plucked for himself from the wreckage. She didn’t know Adam, knew nothing of what had happened with Adam, neither what happened between Neil and Adam and Claire nor between Neil and Adam and Rose. Once, rummaging in the miscellaneous drawer in the kitchen, she had stumbled on the photo of the two of them beneath the Faithful Couple. ‘An old friend,’ Neil had told her, and they had both left it at that.

He would love her properly in the end, Neil thought, as he ducked out of the taxi at the corner of his street. He was almost there. He stepped out distractedly to cross the road; a blue, by-the-hour bicycle swerved to avoid him (between the bikes and the susurrating electric cars, aural intuition no longer sufficed for London pedestrians). When he reached his building he raised his hand to punch in the entry code, but paused. He stood alone on the pavement for a few minutes before he went upstairs.

Roxanna was watching a box set, all charismatic psychopaths and impenetrable accents. When he bent to kiss her she ruffled his hair, asked if he was all right and was there anything she could do? Leila was in her cot, asleep. He ought to be anxious for her by association, but the two universes felt too disconnected — the unjust Sam universe and Leila’s prelapsarian version — for Sam to be a warning for Leila or Leila a consolation for Sam.

He went into the under-used room they affectedly called the study. Outside, on the pavement, he had decided to go through Claire: a risk, obviously, since he couldn’t be sure that she would cooperate, nor how Adam would respond to her mediation. Still, Claire might know whether Adam was amenable; whether the timing was bad; whether Neil had been forgiven, or could be. He didn’t have an email address for her but the internet soon furnished one, from the contact page of what was evidently her new company: Claire@windinyourhair.com.

Good for you, Neil thought, with a small admixture of regret. One of them had been an entrepreneur after all.

He logged onto his email. He tried to keep it short ( Don’t waste the customer’s time ), deciding not to mention his father, or Leila and Roxanna, but to explain only about Sam. He wrote in a hurry and pressed Send before he had a chance to reconsider. No xxx below the sign-off this time:

Claire

To be honest I can still hardly believe that I’m writing this. I mean, not that I am writing to you now but what happened in the first place. I know its probably too late but I wanted to say again to you and Adam that I am sorry. Please tell Adam this if you think that would be appropriate.

I’ve tried too many times to figure out that evening and all I can think of is that somehow you end up with grudges against the people you care about most. You end up not being able to tell them apart, your failures and the witnesses to them, your friends and why you need them. Anyway I take all the blame on myself. All of it. Please tell Ad that. Tell him it was always my fault and I should have seen that earlier.

Obviously I don’t know how things are with you and the kids although I would love to. I dont even know where youre living. I can see that you’re in business now and I hope that it is prospering. I am getting in touch because I wanted Adam to know about something thats happened. I am sure that he remembers Sam, my nephew, I expect that you remember him too. He and Harry played together once or twice. Seventeen now, amazing.

Читать дальше