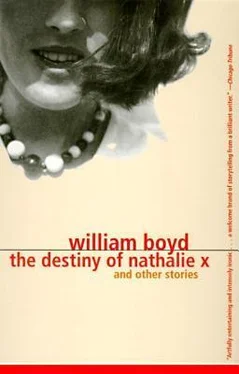

William Boyd - The Destiny of Nathalie X

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Boyd - The Destiny of Nathalie X» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Destiny of Nathalie X

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Destiny of Nathalie X: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Destiny of Nathalie X»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Destiny of Nathalie X — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Destiny of Nathalie X», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He stood now, looking expressionlessly about him, swaying slightly, as if buffeted by an invisible crowd. He appeared at once ill and strong — pale-faced, ugly, dark-eyed, but with something about the set of his shoulders, the way his feet were planted on the ground, that suggested reserves of strength. Indeed, the year before, Ficker had told me, he had almost died from an overdose of Veronal that would have killed an ordinary man in an hour or two. Since his school days, it transpired, he had been a compulsive user of narcotic drugs and was also an immoderate drinker. At school he used chloroform to intoxicate himself. He was now a qualified dispensing chemist, a career he had taken up, so Ficker informed me, solely because it gave him access to more effective drugs. I found this single-mindedness oddly impressive. To train for two years at the University of Vienna as a pharmacist, to pass the necessary exams to qualify, testified to an uncommon dedication. Ficker had given me some of his poems to read. I could not understand them at all; their images for me were strangely haunting and evocative but finally entirely opaque. But I liked their tone; their tone seemed to me to be quite remarkable.

I watched him now, discreetly, as Ficker completed the preliminary documentation and signaled him over to endorse the banker’s draft. Ficker — I think this was a mistake — presented the check to him with a small flourish and shook him by the hand, as if he had just won first prize in a lottery. I could sense that Georg knew very little of what was going on. I saw him turn the check over immediately so as to hide the amount from his own eyes. He exchanged a few urgent words with Ficker, who smiled encouragingly and patted him on the arm. Ficker was very happy, almost gleeful — in his role as the philanthropist’s go-between he was vicariously enjoying what he imagined would be Georg’s astonishment. But he was wrong. I knew it the instant Georg turned over the check and read the amount: 20,000 crowns. A thriving dispensing chemist would have to work six or seven years to earn a similar sum. I saw the check flutter and tremble in his fingers. I saw Georg blanch and swallow violently several times. He put the back of his hand to his lips and his shoulders heaved. He reached out to a pillar for support, bending over from the waist. His body convulsed in a spasm as he tried to control his writhing stomach. I knew then that he was an honest man for he had the honest man’s profound fear of extreme good fortune. Ficker snatched the check from his shaking fingers as Georg appeared to totter. He uttered a faint cry as warm bile and vomit shot from his mouth to splash and splatter on the cool marble of the Nationalbank’s flagged floor.

A GOOD LIFE — A GOOD DEATH

I got to know Ficker quite well over our various meetings about the division and disposal of my benefaction. Once in our discussions the subject of suicide came up and he seemed genuinely surprised when I told him that scarcely a day went by when I did not think about it. But I explained to him that if I could not get along with life and the world, then to commit suicide would be the ultimate admission of failure. I pointed out that this notion was the very essence of ethics and morality. For if anything is not to be allowed, then surely that must be suicide. For if suicide is allowed, then anything is allowed.

Sometimes I think that a good life should end in a death that one could welcome. Perhaps, even, it is only a good death that allows us to call a life “good.”

Georg, I believe, has nearly died many times. For example, shortly before the Veronal incident he almost eliminated himself by accident. Georg lived for a time in Innsbruck. One night, after a drinking bout in a small village near the city, he decided to walk home. At some stage on his journey back, overcome by tiredness, he decided to lie down in the snow and sleep. When he awoke in the morning the world had been replaced by a turbid white void. For a moment he thought … but almost immediately he realized he had been covered in the night by a new fall of snow. In fact it was about forty centimeters deep. He heaved himself to his feet, brushed off his clothes and, with a clanging, gonging headache, completed his journey to Innsbruck. Ficker related all this to me.

How I wish I had been passing that morning! The first sleepy traveler along that road when Georg awoke. In the still, crepuscular light, that large lump on the verge begins to stir, some cracks and declivities suddenly deform the smooth contours, then a fist punches free and finally that crude ugly face emerges, with its frosty beret of snow, staring stupidly, blinking, spitting …

THE WAR

The war saved my life. I really do not know what I would have done without it. On 7 August, the day war was declared on Russia, I enlisted as a volunteer gunner in the artillery for the duration and was instructed to report to a garrison artillery regiment in Cracow. In my elation I was reluctant to go straight home to pack my bags (my family had by now all returned to Vienna), so I took a taxi to the Café Museum.

I should say that I joined the army because it was my civic duty, yet I was even more glad to enlist because I knew at that time I had to do something, I had to subject myself to the rigors of a harsh routine that would divert me from my intellectual work. I had reached an impasse and the impossibility of ever proceeding further filled me with morbid despair.

By the time I reached the Café Museum it was about six o’clock in the evening. (I liked this café because its interior was modern: its square rooms were lined with square honeycolored oak paneling, hung with prints of drawings by Charles Dana Gibson.) Inside, it was busy, the air noisy with speculation about the war. It was warm and muggy, the atmosphere suffused with the reek of beer and cigar smoke. The patrons were mostly young men, students from the nearby art schools, clean-shaven, casually and unaffectedly dressed. So I was a little surprised to catch a glimpse in one corner of a uniform. I pushed through the crowd to see who it was.

Georg, it was obvious, was already fairly drunk. He sat strangely hunched over, staring intently at the tabletop. His posture and the ferocious concentration of his gaze clearly put people off, as the three other seats around his table remained unoccupied. I told a waiter to bring a half-liter of Heuniger Wein to the table and then sat down opposite him.

Georg was wearing the uniform of an officer, a lieutenant, in the Medical Corps. He looked at me candidly and without resentment, and, of course, without any sign of recognition. He seemed much the same as the last time I had seen him, at once ill-looking and possessed of a sinewy energy. I introduced myself and told him I was pleased to see a fellow soldier as I myself had just enlisted.

“It’s your civic duty,” he said, his voice strong and unslurred. “Have a cigar.”

He offered me a trabuco, those ones that have a straw mouthpiece because they are so strong. I declined — at that time I did not smoke. When the wine arrived he insisted on paying for it.

“I’m a rich man,” he said as he filled our glasses. “Where’re you posted?”

“Galicia.”

“Ah, the Russians are coming.” He paused. “I want to go somewhere cold and dark. I detest this sun, and this city. Why aren’t we fighting the Eskimos? I hate daylight. Maybe I could declare war on the Lapps. One-man army.”

“Bit lonely, no?”

“I want to be lonely. All I do is pollute my mind talking to people … I want a dark cold lonely war. Please.”

“People will think you’re mad.”

He raised his glass. “God preserve me from sanity.”

I thought of something Nietzsche had said: “Our life, our happiness, is beyond the north, beyond ice, beyond death.” I looked into Georg’s ugly face, his thin eyes and glossy lips, and felt a kind of love for him and his honesty. I clinked my glass against his and asked God to preserve me from sanity as well.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Destiny of Nathalie X»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Destiny of Nathalie X» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Destiny of Nathalie X» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.