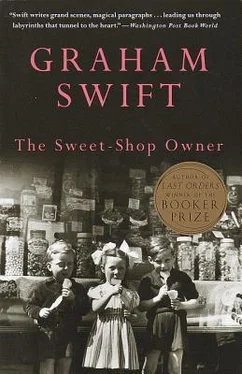

Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Vintage Books USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet-Shop Owner

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet-Shop Owner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet-Shop Owner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet-Shop Owner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet-Shop Owner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Another cup?’ She gripped his mug tightly in her fingers.

‘Please.’ He offered a brief, consoled expression. He knew what she was thinking (did she think he was stupid?).

She would get her reward.

The clock over the door showed twenty past seven. ‘Almost time, eh?’ he said. Traffic was accumulating outside. Figures bobbed along the pavement. Every day you watched them, the same faces, through the cluttered window, and you got to know. They were office cleaners coming home; they were from the vinegar factory; they were the night staff from the telephone exchange. Across, on the opposite corner of Briar Street, was the hair-dresser’s. Sullivan’s: Styling for Men. They’d taken down the red and white barber’s pole which used to twirl endlessly upwards, so that it seemed like a rod of infinite length, for ever passing, disappearing into the bracket that held it. Smithy wouldn’t have allowed that. Smithy had shaved him in the mornings, when Dorry was young. He had sat him in the chair beside the window so he could look across and keep an eye on the shop; and Mrs Cooper, if she looked carefully, could make out his round face, rising from white sheets like a coconut at a fair, swathed in lather. It was a bargain: he got his shave, Smithy got a pinch of tobacco and free magazines for his customers. Then one day young Keith came over, with his tight trousers and a pale face: ‘Please Mr Chapman, it’s Mr Smithy …’

Across the High Street only the café was open. The Diana. Dirty cream paint and wide windows on which the condensation trickled in winter. Who was Diana? A goddess, of something — Dorry would know. They opened every morning at seven, half an hour before him. One saw the regulars going in for their beans on toast or sausage and egg and their hot, treacly tea. Patterns. Most of the old shops over there had gone. The electrician’s had once been a baker’s, the off-licence a coal office, the do-it-yourself shop an ironmonger’s. But the estate agent’s — next to Simpson’s the chemist’s — had always been there. Hancock, Joyce and Jones. At a quarter to nine a grey-haired secretary, prim (all his secretaries were prim, proper things now) with a white handbag would come to open up, stooping with one hand still on the key as she picked up the mail. At nine-fifteen, Hancock, in his dark-blue Rover. On odd days, Joyce. And what of Jones? There were the little rows of notices in the window, all with photographs, some with prices. ‘For Sale, Freehold.’ Yes, Leigh Drive might be there, with the hydrangea bushes under the bay window. Dorry might see to that. Hancock would rub his hands and cast a meaning eye through his window to the shop and then to her. But Jones would never know. Yes, most of the shops were gone. But the Prince William still loomed up, with all that new red fancy-work, over Allandale Road; and the chemist’s shop (though it used to be Lane’s before Simpson’s). And old Powell’s was still there, with the great gold letters, painted to give the illusion of depth, on deep green, over the window. He hadn’t appeared yet. Round the back, stacking boxes. But at eight o’clock he would emerge, pull down his awning and start to put out his display, taking the roundest, firmest oranges, the ripest tomatoes to place outside. They were not the ones you got if you asked, you got the second best from inside. That was the trick of it. Every day in his grey, greasy cardigan; polishing the apples, setting them one by one on the blue tissue paper. A little water on the watercress, a sprinkle on the lettuces, to make them tempt. Unsubtle old shark.

Mrs Cooper reappeared through the plastic strips with his second mug of tea. She glanced at the clock as she approached and caught his eye. Her throat strained. No, he hadn’t forgotten — today of all days. At half-past seven on Friday mornings the shop opened; at twenty-five past he paid her. That was the system.

‘Our usual little business,’ he would say. He would clear his throat; and she would look up, as if she’d forgotten, and instinctively rub the palms of her hands on her nylon shop coat. For this matter of money required clean, immaculate hands.

He opened the drawer of the till. It was already there, made up, in a little brown envelope with a rubber band. And beside it another brown envelope.

‘There.’ She took the envelope and, as always, in one movement, without looking at it, slipped it quickly into the pocket of her shop coat. As if to show it meant nothing to her.

And then, taking her empty hand from her pocket and clasping it with the other, she would give that little disappointed glance.

She turned to lift up the counter-flap and move to the door. But he stopped her.

‘Something else, Mrs Cooper.’

‘Something else, Mr Chapman?’

He had the second envelope in his hand.

‘A little — well, call it — a bonus. As it’s summer. As —’ he couldn’t help lending his eye a sharp twinkle — ‘as it’s the time for taking holidays. There’s twenty-five.’

The eyebrows lifted. Mrs Cooper’s smile never worked.

‘Really Mr Chapman. I —’

‘Now don’t say you shouldn’t.’ He planted the cigar once more between his lips. ‘Sixteen years my assistant. Sixteen. You deserve something now and then.’

Little spasms rose and fell in her throat.

‘My holidays?’ She paused. ‘ My holidays. It’s too kind of you, Mr Chapman.’

But she didn’t look gratitude. Behind her smile her face pleaded, as if she’d expected something else, something more.

But that was all, Mrs Cooper. Take it. The things you want you never get. You only get the money.

‘Keep it. Keep it for me till later.’

He nodded, blowing out smoke. ‘Very well.’ He cocked his head towards the clock. She gave him back the second envelope, lifted the flap in the counter and passed out, as every morning, to unlock the door, unslip the chain and turn round the little plastic Senior Service sign from ‘Closed’ to ‘Open’. Later, when the shop would be closed again, when she would have left and returned to her flat, she would take out the envelopes from her handbag, having spurned them in his presence, and count their contents, running the notes through her fingers; and she would find in the second envelope not twenty-five but five hundred pounds. That would stop her, that would surprise her. She would not know what to do — to phone up, to say, to do nothing. But by that time, by that time, it would be too late.

She was paid.

She returned from the door, straightening the hang of her shop coat, and stood beside him at the counter, awaiting the first customers. He passed his eyes over her vexed, hawkish face, seeing, beyond it, arms lifted in a golden sea. And she, not attempting to return the gaze, stared at the sun, the shaft of sunlight slanting through the shop, falling on the smoke from Mr Chapman’s cigar, on his knotted, tarnished hands which rested on the counter, on the words on the front page of the uppermost paper in the pile between them. ‘PEACE BID FAILS.’

5

‘A gem of a site.’

It was old Jones who spoke, in his black greatcoat, with his florid cheeks and stoop, and his bunch of dangling keys like a jailer’s. And they were standing, Jones, himself, and his brother-in-law Paul, in that shop that would one day bear the name Chapman.

Jones sniffed the damp air. He was nearly seventy, they said; had made his pile, but he wouldn’t retire. And young Joyce and Hancock, over in his wood-panelled office, were waiting for him to die so that they could take his place and move the name on the letter head from first to last. ‘Needs going over. But a gem of a site. Corner. Station close by. Good will of previous proprietor. And how many other newsagents along this stretch?’ He ran a finger through the dust on the counter and flicked it away. ‘You’ll be all right here.’ The face, sucking its own lips, was almost apologetic. He was old, tired of business, he no longer cared to encourage or discourage; yet he wouldn’t stop working. Perhaps he knew already (one did know): two weeks after his retirement, the fatal stroke. A further week, speechless as a dummy, then he died. And that was a month after he’d wheezed to him, coming in to buy chocolates for his wife, ‘If you sell, watch Hancock.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet-Shop Owner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.