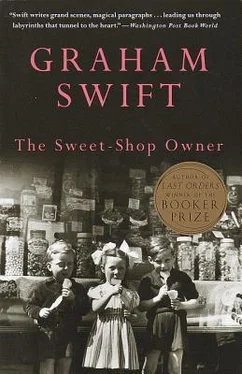

Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Vintage Books USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet-Shop Owner

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet-Shop Owner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet-Shop Owner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet-Shop Owner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet-Shop Owner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Goodbye then.’

‘Goodbye Janet.’

He had called her Janet.

38

Half-past five. It seemed as if he were making his escape. He had always known it would be like this. Tomorrow they would discover the fraud, the deception: the costume discarded, the things left untouched so as to make it seem nothing had changed.

He watched Mrs Cooper lug her shopping bag across Briar Street and pass out of sight round the corner where Smithy’s pole had twirled. Then he lifted up the flap in the counter. There was a timely gap in the succession of customers. The pain in his chest gave little evil prods. He moved to the door, twisted round the plastic sign to ‘Closed’, released the latch and slipped across the two bolts at the top and bottom.

There. It was done.

He moved back to the counter. Now the ‘Closed’ sign was up and the door locked it seemed he was somehow shut off from the flow of the High Street. The noise of the homeward traffic, thickening on the near side of the road, seemed muted, and the cars and pedestrians passing by the window might have been moving in some vast sun-barred aquarium.

He sat down on his stool. No need to hurry. Half-past five. They would be coming home now, in their hordes; work over, pleasure in store. Down at the station the trains would unload from Cannon Street and London Bridge; hot and crumpled commuters, sweaty and fidgety from the stifling carriages, but freed, at last. Across the road the Prince William would open its cool saloons to receive them. The landlord would be blessing the sunshine. Thirsty weather: good weather for trade. And along the High Street the shops which kept the normal hours would be closing. Business done: life begins. Simpson would count his cash. Powell would take in his trestles. In his wood-panelled office, behind the shading blinds and with the electric fan whirring on the filing cabinet, Hancock would lock away papers, give a terse good-night to his departing staff, and even though it was a warm, careless evening in June, would make sure his jacket was buttoned, his tie in place, his shoulders straight before leaving.

He looked round at the crowded shelves of the shop. The cellophane wrappers crinkled, as ever, as under some invisible, covetous touch, and the toys dangling and perched in the Briar Street window seemed to jostle visibly, as if the plastic dolls, action-men and model knights in armour, whose promise was to be like the real thing, were actually about to come to life. He felt like a conjuror, amidst his tricks, for whom, alone, there is no illusion.

He opened the till drawer. Everything must be done as normal. He pulled back the spring-clip over the five-pound notes and started to count.

At Briar Street they would expect to call, as usual, walking up from the station, for their little trifles of tobacco and newsprint. But they would find the shop closed. Chapman — who never closed; who was always open, Sundays too, raking in the cash, which he never had time to spend; who was always there with your cigarettes or paper, as late as seven in the evening. They would rattle, annoyed, at the door and rap on the glass; and peering in they would see him, sitting in his usual place, still and unperturbed, like the statue of someone who had once been a shop-keeper. See — there was someone already, and another, looking at the ‘Closed’ sign as if it did not mean what it said and staring in, hand held over eyes, as into the cage of some unobliging pet. He raised a hand and moved it slowly in a lazy, indifferent wave. They would gather perhaps at the corner; try to force the door. And perhaps he should let them. Fling back the bolts. Let them swarm in to plunder and grab. Gorge themselves on sweets and ice-creams, fight over the boxes of Havanas. And he would sit motionless in the midst of the looting, as if, after they had emptied the shelves, they would set to work to dismantle his effigy.

He lifted himself from the stool onto his feet. The pain seemed to rock inside him like a weight that would over-turn him. He steadied. Not now. But he wouldn’t take a pill. People were stopping now and then at the door and trying the handle but he took no notice of them. He started to count the one-pound notes, then the coins. Everything must be done as usual; everything must look the same. He carried the money in the little pink and blue bank bags and placed them inside the green cash tin inside the safe. Then he made a note of the figure inside the maroon cash book. These were actions he had carried out so many times that he could do them almost without thinking; and yet, this time, they seemed like unique operations, as if he hadn’t counted up and closed numberless times before. He shut the cash book. £92. Twenty years ago you would have been glad to take ten. He put the cash book in his briefcase and locked the safe. He had got the safe in ’49. There were scratch marks on its door and the black paint on the handle was worn away to the metal from years of opening and shutting. He went back into the shop; switched off the electric fan, checked the fridge, set the time switch for the display lights, put his hand down to the lever beneath the telephone which activated the burglar alarm — but then withdrew it. It didn’t matter now — they could break in and steal. The shop door was already fastened. He would leave by the rear door in the stock room. It led to a narrow passage which turned at a right angle into Briar Street. For some time he had meant to fit a better lock on it. But today it could be left unlocked. Once outside he could even throw away the keys. Toss them out into the swirl of the High Street.

Someone else was rattling at the door, looking in and making pleading, desperate gestures. He took no notice. He looked at the counter and the shelves. Then he turned his back on the shop and passed through the plastic strips. Best to go by the back. Actors slip out by back-exits, leaving their roles on the stage. He moved to the wash basin to rinse his hands and comb his hair. He expected to see for a moment, in the mirror, the face of a young man, unchanged, with a thirties stiff collar and a waistcoat.

He put on his jacket, took up his briefcase and then opened the rear door. He walked along the passage-way, where, here and there, tufts of grass and dandelions grew in the cracks in the concrete, then out, across the wide pavement, by the cinema adverts, to the car.

The car was drawn up, half on the pavement, pointing away from the High Street. Normally he drove down Briar Street, avoiding the awkward U-turn out into the main road. But it didn’t matter now. Normally he didn’t shut at half-past five; normally he didn’t walk to Pond Street. A sudden exhilaration came over him. He took a packet of cigars from under the dashboard and lit one. The doctor had warned. Then he swung out, in a break in the traffic, into Briar Street and out into the queue of cars in the High Street.

He did not look back. Not at the front window, with his name, in blue and gold, emblazoned above; nor at the door, at which they were still tapping and rattling perhaps, trying to discern him within. No, there was no longer a sweet shop owner.

The sun shone from the direction of the town hall, dazzling on car bonnets and in the glass frontages where Simpson’s and Hobbes’ had already shut shop. Only the Diana was open, dilatorily serving out limp salads and milk-shakes, the manager chasing flies behind the counter. The traffic moved slowly, in two lanes, down towards Allandale Road and the traffic lights by the common. Always congested at this time; both directions. Drivers were propped on elbows against open windows, holding up idle arms and drumming irritably with their fingers on car roofs. A motor-cyclist revved impatiently. And on the pavement the pedestrians walked with that peculiar agitation of people travelling home from work on a Friday evening. Why did they look so intent, so vexed, when, up above, the lime trees shone, green-gold, in the sun?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet-Shop Owner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.