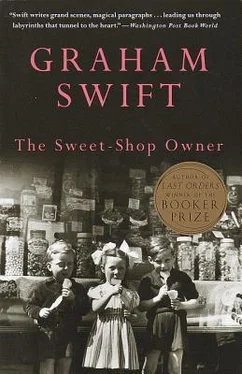

Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Vintage Books USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet-Shop Owner

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet-Shop Owner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet-Shop Owner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet-Shop Owner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet-Shop Owner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Thank you Sergeant, carry on.’

‘Sh-holdah kit bags! Lehf!.. Lehf …’ Over the crunching gravel.

*

He didn’t mind the orders, the regimentation. He was a performer, wasn’t he? Give him the uniform, tell him what to do, he’d do it. And it was easy to pretend to be a soldier. To salute, to obey, to clomp one’s black heels, even with a limp, over the wooden barrack-hut floor. And see, he dealt as before (how consistent fate was) with items, with things stacked and piled and arranged in long rows under the curved roof of the store block; with lists, inventories (the carbon from the duplicated Army forms came off on your hands along with the blanco from old webbing), stock lists, issue lists, delivery lists. There was a counter, wooden and scoured by continual use (but the Quartermaster made them polish it every day) from behind which you watched the faces entering and passing, passing, keeping the line moving. They never seemed to stop, and you remembered them only by the numbers you recorded on the forms: 120 capes, 120 helmets, 240 side-packs.

‘There,’ said Private Rees, from Swansea, sallow-faced and listless, removing his gold-rimmed glasses and squinting at them (for that was his reason for not seeing action), ‘There’s another lot done.’

And up the road they were coming already, the next lot, in the canvas-topped lorries, past the flashing leaves, past the striped pole by the guard-house, waiting to be made into soldiers.

‘Right!’ snapped the sergeant. ‘Now lissen-a-me. Look after your kit. Remember: what you ’ave don’t belong to you. When the war’s over the army’ll want it bloody back!’

They badgered him and Rees, and the other stores clerks, because they were safe. And the rest would go and fight. They slept in their own quarters for those permanently on camp but they mixed in the mess hall with the passers-through for Issue of Kit and Basic Training. Private Rees would not be drawn. ‘Bugger off,’ he said, ‘Tell them to bugger off, Willy boy.’ But he said (did they think he was stupid?): ‘Someone has to mind the store.’

The long barrack huts with their tiers of bunks, the mess hall and the echoing bath-house reminded him of school: the sweaty blasphemy of changing rooms, flaunted man-hoods, the belligerence of the football pitch and the running track. They’d wanted ‘action’ then, in ’30 and ’31, trailing home, tingling with exercise, out of the school gates. A restlessness plagued them which turned their games into something more than games. The real thing, the thing itself: let us have that. And for a moment their eyes were blind to the rows of still chestnuts, the black lines of railings. They’d sat in the history lesson and chafed at its dryness — would nothing happen? — but here suddenly was ‘History’. So Private Rees said, smacking his lips over a newspaper bearing the news of the occupation of Paris: ‘History, that’s what it is.’ As if the statement would save him, immune as a rock, from an invasion of Germans and all the outrages of war. And here suddenly was the real thing. And yet how did it express itself? In barrack huts and wire fencing, in numbers, inventories, lists? 360 capes, 360 helmets, 720 side-packs. What was the connection?

They badgered him in the mess hall. His limp became the target for mocking jokes, and they looked in his face with the shifting looks of schoolboys for signs of injured pride, for signs that their enforced code of ‘action’ had proved its worth by delivering a sting. But he gave no sign. For over the dinner table, over the white cloth with the blue border, on the evening his final papers and his rail warrant had come, she’d looked at him, looking for the same signs, looking for ‘deeds’ and ‘action’, but she’d not found them.

‘Count your blessings,’ she’d said. ‘Why should you go and get yourself killed?’

What firmness. She sat in the chintz chair listening to the wireless bulletins, scanning the papers which spoke of the war in Finland, the threat of air raids, taking note of the facts, as if the course of things was predictable and she had only to observe its fulfilment. Let bombs drop: she wouldn’t jump. And when the note-taking was done she would throw down the paper, switch off the wireless (before it burst into morale-boosting song), and, getting up, stare momentarily at the window — though not through it, for it was covered by the dark black-out curtain, and beyond it, anyway, the garden was dank and dead, under that first bleak winter of the war. But she stared. No, it wasn’t war, destruction that she feared. It almost protected her, that great ominous blackness, as if she knew where she stood with it — shielded her from sunlight; and she was saved perhaps, so long as there were bulletins and blackness (her body was like a lamp, there at the window) from bright moments which urged: No, there is beauty, we do not belong to history.

But that was before he left for his camp in Hampshire and before she went with her mother to her Aunt Madeleine’s in Aylesbury (for her family had stepped in nobly in the hour of peril to pluck her from the rain of bombs that would fall on London). Leigh Drive stood empty. Her plates and glass were wrapped in packing cases; the pictures taken down from the wall, the wedding photos locked in a drawer. How many landmarks had passed already, swept suddenly far behind by the advent of war? Was it only in ’37 he’d been the printer’s assistant, coming home in the evening to Mother and Father, who’d never heard of Irene Harrison? And how many new landmarks had replaced them? Leigh Drive, the shop; housing his identity, but not for ever; and perhaps never really; for see, they stood empty, and, look again — the bombs were falling. Two fell in Briar Street, one stripped the lime trees outside Powell’s; and one, crashing down near the Surrey canal, flattened old Ellis’s print-works.

What would become of the shop? What would become of the sweet jars, the ice-cream, the magazines? He pinned up one of those comic notices: Closed for the Hostilities. ‘It will keep,’ she said. ‘It must keep.’ Wars pass but sweet shops remain.

‘Dear Willy,’ she wrote from Aylesbury, ‘We are doing our bit. Aunt Madeleine is digging the back garden. I am collecting coat-hangers. Mother writes to Jack and Paul. Mother especially does her bit. Father is staying at Sydenham. Sticking to his post. He demands the keys to Leigh Drive. He won’t get them. Mr Smithy is keeping an eye on the shop. He says he’ll get someone to board up the windows and he’ll send on any mail.’

He replied: ‘Am doing my bit too,’ and wrote, ‘1980 helmets.’ For that was how they told off the war, in tin helmets and letters.

‘Mother worries about Father in London. You must have read about last week’s raids. He sleeps alone at Sydenham, in the cellar. Misses Jack and Paul. He’s by himself now at the laundry. Mother suggests I go to give him some “support”, but I think it’s really Father’s idea. He says he’ll protect me from bombs. But I’d be more scared of staying at Sydenham.’

There was this tone about her letters as if she were writing from the thick of the fighting.

He dropped the wallet just as the sergeant came in the door and called attention. He was folding her letter inside it and then it slipped from his hand. The sergeant loured, flexed his shoulders and stooped to pick it up. ‘Your wife, Chapman?’ he said, looking at the photograph. A beach photographer had taken it in Swanage. The sun was in her face. ‘ ’Oo’s a lucky man then?’ He spoke loudly so everyone in the hut should hear. Then he tossed the wallet back and sauntered out through the far door, flicking with his baton at a pile of blankets, looking for another reason to shout.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet-Shop Owner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.