David Vann - Legend of a Suicide

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Vann - Legend of a Suicide» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, Издательство: Penguin Books Ltd, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Legend of a Suicide

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books Ltd

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Legend of a Suicide: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Legend of a Suicide»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

follows Roy Fenn from his birth on an island at the edge of the Bering Sea to his return thirty years later to confront the turbulent emotions and complex legacy of his father's suicide.

Legend of a Suicide — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Legend of a Suicide», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I saw two points on one side of the buck’s horns, making it legal to shoot. I levered a shell in the chamber and raised my rifle, but my father put his hand on my shoulder.

“You have time,” he told me. “Rest an elbow.”

So I knelt down in the bed, rested my left elbow on the side of the pickup, much more stable, and looked through the peep sight, lined it up with the deer’s neck. I couldn’t shoot the deer behind the shoulder, because its body was hidden by the trees. I had only the neck, long and slim. And the sight was wavering back and forth.

I exhaled and slowly squeezed. The rifle fired and the neck and head whipped down. I didn’t even notice the hard kick or the explosion. I could smell sulfur, and I was leaping over the side of the pickup and running toward the buck. My father let out a whoop that was only for killing bucks, and it was for me this time, and then my uncle did it, and my grandfather, and I was yelping myself as I ran over ferns and fallen wood and rock. I charged through the stand and then I saw it.

Its eyes were still open, large brown eyes. A hole in its neck, red blood against soft white and brown hide. I wanted to be excited still, I wanted to feel proud, I wanted to belong, but seeing the deer lying there dead before me in the ferns seemed only terribly sad. This was the other side of Faulkner, conscience against the pull of blood. My father was there the next moment, his arm around me, praising me, and so I had to hide what I felt, and I told the tale of how I had aimed for the neck, beginning the story, the first of what would become dozens of tellings. And I slit the deer with my Buck knife, a gift from my father, slit the length of its stomach, but not deep, not puncturing innards. It seemed a monstrous task. I had both hands up to my elbows in the blood and entrails — not the overpowering foul bile of a deer that’s been gut shot but foul nonetheless — ripping out the heart and liver, which I would have to eat to finish the kill, though luckily they could be fried up with a few onions first, not eaten raw. I pulled out everything, scraped out blood, and cut off testicles, then my father helped me drag it to the truck. He was grinning, impossibly happy and proud, all his despair gone, all his impatience. This was his moment even more than mine.

The next day, in the lower glades — wide expanses of dry yellow grass on an open hillside, fringed by sugar pines — I saw another buck. It was in short brush off to the side, a three-pointer this time, bigger. I aimed for the neck again, but hit it in the spine, in the middle of its back. It fell down instantly. Its head was still up, looking around at us, but it couldn’t move the rest of its body. So my father told me to walk up from behind and finish it off execution-style, one shot to the head from five feet away.

I remember that scene clearly in all its detail. The big buck and its beautiful horns, its gray-brown hide, the late-afternoon light casting long shadows. After all the rain, the air was clear and cool, distances compressed, even in close, as if through a viewfinder. I remember staring at the back of his head, the gray hide between his antlers, the individual hairs, white-tipped.

“Be careful not to hit the horns,” my father said.

I walked up very close behind that deer, leaned forward with my rifle raised, the barrel only a few feet from the back of his head, and he was waiting for it, terrified but unable to move. I could smell him. He’d turn his head around far enough to see me with a big brown eye, then turn away again to look at my father. I sighted in and pulled the trigger.

The next year I began missing deer, closing my eyes when I shot. We were on an outcropping of rocks over the big burn, an area consumed by fire years before, with only shorter growth now. A buck leapt out from a draw and bounded across the hillside opposite us. My father hunted with a.300 Magnum, a gun he’d bought for bears in Alaska. It was an outrageous caliber, sounded like artillery, and would tear the entire shoulder off a deer.

My dad was an excellent shot, but this deer was far away and moving fast and erratically, dodging bushes and rocks. I was firing, too, but only pointing the gun in the general direction, closing my eyes, and pulling the trigger. I opened my eyes in time to see one of my bullets lift a puff of dirt about fifty feet from the buck, and my father saw this, too. He paused, looked over at me, then fired again.

That was the last time we hunted, and we never talked about what had happened.

I turned thirteen that fall, after the hunt, and I saw very little of my father. At Christmas, he was having troubles I didn’t understand, was crying himself to sleep at night. He wrote a strange letter to me about regret and the worthlessness of making money. At the beginning of March, he asked whether I would come live with him in Fairbanks, Alaska, for the next school year, eighth grade. I wanted to spend time with him, but I was afraid of his despair. I was afraid, also, of the kids I knew in Alaska, who were already doing drugs at thirteen. I wanted badly to say yes, but I could feel a terrible momentum to what my life would become in Alaska. So I said no.

Two weeks later, my father called my stepmother in California, where she’d moved after their divorce. He was alone in Fairbanks in his new house, with no furniture, the ides of March, cold, sitting at a folding card table in the kitchen at the end of a day. He had broken up this second marriage the same way he had the first, by cheating with other women. And now my stepmother was moving on. She’d found another man and was thinking of marrying him. My father had other problems I would learn about later, including the IRS going after him for tax dodges in South American countries, failed investments in gold and a hardware store, unbearable sinus headaches that painkillers couldn’t reach, in addition to all the guilt and despair and loneliness, and he told my stepmother, “I love you but I’m not going to live without you.” She was at work in an office and couldn’t hear well. She had to duck behind the door with the phone and ask him to repeat what he had said. So he had to say again, “I love you but I’m not going to live without you.” Then he put his.44 Magnum handgun to his head, a caliber bought, like the.300 Magnum, for grizzlies, capable of bringing a bear down at close range, and he pulled the trigger. She heard the dripping sounds as pieces of his head came off the ceiling and landed on the card table.

After my father’s suicide, I inherited all his guns. Everything except the pistol. My uncle wanted to get rid of that, sold it right away. But I was given my father’s.300 Magnum rifle, and though I had stopped hunting, I began using that rifle.

I learned to break it down into several parts that I could fit into my jacket. Late at night, when my mother and sister were sleeping, I rode my bike through our suburban neighborhood into the hills. I’d ditch my bike, find a spot hidden in trees, and reassemble the rifle. I sat in the braced sitting position, elbows on my knees, that my father had taught me, calmed my breath, and eased slowly back on the trigger. The recoil was so powerful it literally knocked me flat. But nothing was more beautiful to me than the blue-white explosion of a streetlight seen through crosshairs. The sound of it — the pop that was almost a roar, then silence, then glass rain — came only after each fragment and shard had sailed off or twisted glittering in the air like mist.

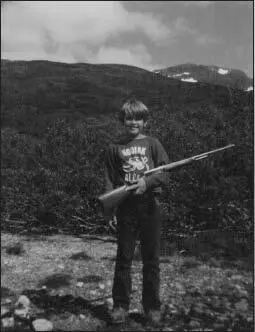

The author in Alaska at age nine, with the.30–30 his father passed down to him.

I also sighted in on people. A man with the curtains open in his living room, the crosshairs on his chest, a shell in the chamber, the scope powerful enough I could see him swirl the drink in his hand. I had done this with my father. When he spotted poachers — hunters trespassing on our land — he would have me look at them through the scope.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Legend of a Suicide»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Legend of a Suicide» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Legend of a Suicide» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.