David Vann - Legend of a Suicide

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Vann - Legend of a Suicide» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, Издательство: Penguin Books Ltd, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Legend of a Suicide

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books Ltd

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Legend of a Suicide: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Legend of a Suicide»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

follows Roy Fenn from his birth on an island at the edge of the Bering Sea to his return thirty years later to confront the turbulent emotions and complex legacy of his father's suicide.

Legend of a Suicide — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Legend of a Suicide», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Finally, I need to thank my family, because it was an uncomfortable topic I was writing about — my father’s suicide — and there’s exposure in these stories. They’re fictional, but based on a lot that’s true. My stepmother, Nettie Rose, was especially generous in helping me talk through everything for several years. She had faced a lot of other deaths in her life and seemed fearless to me then.

P.S. Insights, Interviews & More…

About the author

A Conversation with David Vann

What’s your earliest memory?

Trying to tie my shoes in Ketchikan, Alaska. An early sign that things come undone easily.

Who are your favorite writers?

I’m a sucker for landscape description, so I love Elizabeth Bishop’s poems, Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping , Annie Proulx’s The Shipping News , and Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian .

Why did you write this book?

After my father killed himself, my sister felt a drop on her cheek on a cloudless day and knew that it was his way of saying good-bye to her. My mother saw him vividly in a dream, again saying good-bye. But nothing happened for me. Just a void. So this book is my attempt to reach him again, to bring him back to life.

Why did you write about his suicide as fiction instead of nonfiction?

My father killed himself when I was thirteen, and for three years afterward, I told everyone he had died of cancer, because the way he killed himself felt too shameful. And I also didn’t quite believe his death. I lay awake at night and could see him running through the snow in Alaska, trying to come back to me. Everything about his death was mythical from the start, and Alaska is that way for me, also. As a kid in the rain forest of Ketchikan, I ran from imaginary wolves and bears, but we had real ones, too. I had this class once with Grace Paley in which she told us that every line in fiction has to be true. It has to be a distillation of experience, more true to a person’s life than any moment he or she has actually lived. So this book is as true an account as I could write of my father’s suicide and my own bereavement, and that was possible only through fiction.

“Everything about his death was mythical from the start, and Alaska is that way for me, also.”

About the book

My Father’s Guns

First published in Men’s Journal , July/August 2009, reprinted in Esquire UK , November 2009

MY FATHER gave me my first gun at age seven. It was a Sheridan Blue Streak pellet rifle, powerful enough to kill squirrels if I hit them in the right spot, behind the shoulder. The giving of the gun was a ritual, my father’s pride and pleasure as he showed me how to pump the gun, how to pull back the bolt. He even read a poem from Sturm, Ruger & Co. about a father and son, using it to teach me safety: never point a gun at anyone, never leave a gun loaded but always assume a gun is loaded, always keep the barrel pointed down. This was very soon after he and my mother had divorced, and we had only the weekends now. Roaming his ninety-acre ranch near Lakeport, California, one of those weekends, I didn’t realize the rifle was pumped and loaded, and it fired as I walked. Luckily the barrel was pointed at the ground. But my father turned around, the disappointment clear on his face, and my shame was nearly unbearable.

The next year, when I was eight, he gave me a twenty-gauge shotgun, for hunting dove and quail. That gun felt inevitable, as if it were a given that couldn’t be turned away from. As if we were put here to hunt and kill, and the only true form of a day was to head off with a gun and a dog, hike into the hills for ten or twelve hours, and return with meat and stories. That shotgun became an extension of my body, carried everywhere, the solid heft of it, cold metal, a sense of purpose and belonging. I gazed at it in the evenings, daydreamed of it during the week at school, looked forward to when I’d head out again.

When I was nine my father gave me a.30–30 Winchester lever-action carbine, the rifle used in all the Westerns, and he actually went down on one knee when he presented it to me, holding it in both hands, as if it were a ceremonial sword. “This is the rifle I learned on,” he said. “This is what we pass down through the family. The rifle I hunted with when I was a boy, the rifle I shot my first buck with, the rifle you’ll shoot your first buck with. It’s a good gun, an honest gun, with only a peep sight, no scope. You won’t be shooting long range, and you’ll need to hit the buck behind the shoulder.”

He moved back to Alaska then, where I had been born and spent my early childhood, and when I visited, a tourist now, we flew into a remote lake with a float plane, camped on a glacier, and slept with our rifles loaded, a shell in the chamber, beside our sleeping bags. “If a bear comes,” he told me, “the bullet from a.30–30 will only bounce off his skull, or bury in his chest and not do anything. You’ll have to hit him in the eye or in the mouth if he roars.” There was no moon. We were the only humans for a couple hundred miles, and I lay awake imagining the bear attacking my father in the middle of the night while I tried to sight in on an eye in the darkness. This felt like the nature of our relationship: I saw him only during vacations now, and he would give me tasks that seemed impossible, including making up for lost time. We were supposed to cram half a year into a week.

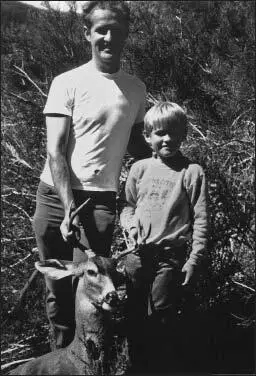

Age seven, with his father and a buck his dad bagged on California’s White Ranch

I shot my first buck at eleven. A rainy weekend in September 1978, on the White Ranch, my family’s 640-acre hunting spread in northern California. A two-hour drive away from civilization, it was the entire side of a mountain, with high ridges, enormous glades, pine groves and springs, ponds and switchbacks, an old burned area, and even a “bear wallow.” Our entire male family history was stored in that place. As our Jeep pickups crawled along the fire roads, my father and uncle and grandfather would tell me the stories of past hunts. Places of triumph and shame, places where all who had come before were remembered.

My father flew down from Alaska every fall for this hunt. He was in his late thirties then, a dentist like his father, in years of despair leading toward his suicide. Grim-mouthed, hair receding, thin and strong, impatient. But he hadn’t always been like this. He’d hunted here since he was a boy, and he was known then for being lighthearted, a joker. Whenever he came back here, he could see each year recorded in the place, wonder at who he had become.

At eleven, though, I could think only of who I would become. Shooting my first buck was an initiation. California law said I wasn’t allowed to kill one until I was twelve, but family law said I was ready now.

I imagined sneaking up through pine trees or brush to make my first kill, but the weekend was rainy, so we hunted directly from the pickup. It felt unfair, even at eleven. The deer would be standing under the trees in the rain, flushed out from the brush. I stood in the back of the pickup with my father, holding on for the ruts and bumps. And when I saw the buck, hidden mostly by a stand of half a dozen thin trunks, I immediately felt pounding at my temples. “Buck fever,” we called it. Heart going like a hammer, no breath. The moment of killing something large, another mammal, something that can feel individual, that moment is not like any other. You could call it many things — brutal, wrong, irresistible, natural, unnatural — but what it felt like to me was straight out of Faulkner, the rush of blood and belonging, of love for my father. This was the largest moment of my life so far, the moment of being tested.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Legend of a Suicide»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Legend of a Suicide» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Legend of a Suicide» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.