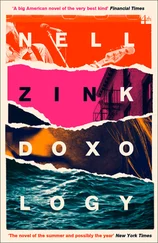

Lee had been sexy to her at one time. But it wasn’t because they had a relationship. It was the opposite. Because they didn’t. And then she stupidly became his partner. She wasted her love on a wolf. What an excellent use of her youth and beauty! She glared at the typewriter, blaming it for her existential angst.

She finished the play with the nun sacrificing the other nuns one by one to protect the death squad commander from the revenge of his dead death squad’s death squad friends. She tore it into very small pieces and buried it deep in the trash can.

Over milk and cookies after Karen’s return, she confessed to Karen that she had no idea what Karen wanted out of life. “You’re a cipher,” she said. “A mystery. What are your ambitions and desires? When I was your age, I wanted to write plays.”

“I want to get good grades and go to college.”

“And what are you going to do when you get there?”

“How would I know? I need to get there first and see what it’s like. There are all these majors that sound neat, but I don’t know what they are. Like ‘sociology.’ What is it?”

Meg sighed. “Don’t play dumb. Come on. If money were no object, where would you want to go to college?”—Meg had something specific in mind involving her now rather large collection of cash. Her native, self-compounding black/WASP/drug dealer aversion to public display — her low profile — need not apply to college tuition. Busybodies who learned that Karen was away at a Seven Sisters school would assume the numbers added up because she was black.

“Wherever Temple gets in.” Seeing her mother’s expression, she added, “You didn’t even go to college! So don’t pretend you know what it’s like to be away from your friends.”

Karen took a few cookies off the plate and went outside to lie in her hammock. Meg could see her from the window. Having developed a sensitivity to poison ivy, Karen seldom went in the woods anymore, but the effects of her early training persisted. She would stare at the sky as if it were a TV — as if clouds were more fun than a barrel of monkeys, as Dee put it.

Karen’s mind was racing. She had just finished reading Malaparte’s Kaputt and was deeply moved. (The library, like the thrift shop, specialized in the leavings of the elderly dead.) She wanted to talk to Temple about it. She seldom confided in Meg. Like many fresh human beings new to the world, Karen assumed people’s thoughts resembled the things they said. So she didn’t know her mother very well. She had no idea.

Lomax’s financial situation had improved to the point where he was considering investing. Not in anything megalomaniac, like his business partner the ex-SEAL who read Soldier of Fortune and wanted to buy an Antonov and start flying to Chihuahua, but in something more pleasant, the overture to a well-earned retirement. He had always wanted to retire by age thirty. “Live fast, die young,” he would say as he cracked another beer on his grandmother’s flowered glider, barely having moved in ten days except to lie down on her sleeping porch. Lassitude was an accepted hallmark of Southern culture even among Indians on disability, perhaps even more so if their non-Indian (“Irish”) ancestors were mostly Tajik und Uzbek like Lomax’s.

Nonetheless, as it is for many people living more conventional lifestyles, his retirement was supposed to be more exciting than his working life had been. His plan was that in retirement he would fish on the ocean. He had his eye on a deep-V cabin cruiser belonging to a friend who owed him money. He knew it was only a matter of time before it would be his. Then he would lounge on the upholstered bench seat that curved around the back of the boat and watch big marlin come to his lure. He wasn’t yet sure how it worked, but he knew that if you played your cards right, you could land dangerous-looking fish that tasted scrumptious (a word that always wormed its way into his vocabulary after three or four days with his grandmother).

Then came the day when the friend handed over the keys to the boat, saying he had no place to park it anymore since he was moving to a hiding place at an unnamed location until it all blew over. Lomax priced the boat at eight grand and accepted thanks for his generosity. Except he had no place to park it either. He visited his more ambitious friend.

“I was thinking to buy a motel in Yorktown and get a boat slip up there,” Lomax said. “But shit, it all sounds like work. Even with no guests and no vacancies, you still got to keep the books. What the shit kind of a retirement is that? And Flea and Poodle, when I tell them they got shifts on reception, they’re going to lynch my ass.”

“Stop right there, my friend,” the Seal said, holding up his hand.

The Seal gathered his thoughts in silence, then unexpectedly, lyrically, described a house he’d seen on the Eastern Shore. It sat in meadows spiked with volunteer pines and surrounded by serious forest, a big old wooden mansion with porches on every side and a widow’s walk around the roof lantern. From the widow’s walk there was a view across the barrier island to the ocean. There was a boat ramp and a dock on the creek. An earthly paradise. And it belonged to the state for back taxes. Nobody wanted it because you couldn’t develop it. It had an endangered species.

“Won’t that get hairy?” Lomax asked. “Walking into the state and telling them I want to buy a wildlife refuge for cash?”

“Delmarva fox squirrel, dude.”

“Oh, shit,” Lomax said. “Oh, shit!” In retirement they both were consistently kind of wasted and their dialogues were often as cryptic as their thoughts, but Lomax knew exactly what the Seal was trying to say.

When he brought the subject up to his father, he was initially met with raised eyebrows. However, Lomax’s gift was an undeniable godsend for the Virginia Squirrel Conservation Association, established many years before and, by dint of his father’s hard work and dedication, now boasting twenty members, only nine of whom were over seventy-five. The association was happy to accept a substantial windfall in the form of a dedicated capital gift from an anonymous donor. It was a tax-exempt charity, and donations to date had totaled $148. Purchase of a rodent reserve of international importance would catapult it from irrelevance to significant standing in the conservation world. Lomax’s father shook his hand with real appreciation, pumping it up and down. It seemed to Lomax a benevolent fate had intervened to launder his income in a way he never anticipated. As he left his parents’ house he dropped to his knees, crossed himself, and thanked the Great Spirit.

The house on the Eastern Shore had originally been named Kenilworth, but the new sign said KEEP OUT. Lomax called it Satori. It was posted NO HUNTING NO TRESPASSING all the way around its vast perimeter. Except for the big clearing and some areas of open water, it was second-growth wilderness, full of old trees. Lomax and the Seal took up running around. Literally: running around. They would drop acid and race around the clearing in circles like dogs rocketing, and then top it off by diving from the little sandbank at the edge of the old bowling green and rolling over the soft turf like pill bugs, tumbling blissful and invulnerable. With time the Seal became softer and rounder from rolling, Lomax leaner and harder from running. Huge skies of seaborne cloud turned pink in the light of sunset, and swallows and seagulls met and turned away from each other in the air. Thunderstorms brought rains like an Indian monsoon, wet and fast as invisible buckets slicing through the air and sand on their way straight down to China. Twice a week they rubbed filet mignon with garlic and barbecued it. Fridays they alternated crab feast, lobster, and scallops.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу