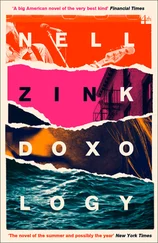

Meg spent the parties sitting at a redwood picnic table with other moms, doing what they all did: eat and offer color commentary on the children’s mode of running wild that year. She spoke little and employed her broadest accent. Occasionally a mother would jump up and intervene if things got too colorful, or do some shouting at the edge of the clearing if a group of children vanished in the greenbrier for too long.

Since the mothers were not all related, the gossip was not intimate. Clans not present came up for criticism for allowing first cousins to date each other, or beloved elders to retire to the woods behind a supermarket. (It was accepted practice to let your husband camp out in summer near a source of sweet wine and steaks past their sell-by date, but you had to take him back in winter.) When it started to get dark and the bugs came out in force, Meg would take Karen home. Karen would be limp from playing, as though she had been scoured inside and out, an empty husk awash in soda pop and cake crumbs.

Karen lacked playmates. She lacked toys. Without a TV or playmates she was unlikely to figure out about toys. She wasn’t a complainer. Meg saw that Karen was humble and a stranger to envy. Fads came and went without a peep from her. She felt no more entitled to an Atari than she would have to a Lamborghini. The gift of a Tootsie Roll made her quiver. She would nibble shavings off it like a mouse.

Meg was not overprotective, but she had doubts about Karen’s going into the woods alone. Turkey season seemed especially risky. Karen moved as irregularly as a bird, and she was about the height of a turkey. “This is like Red Riding Hood’s riding hood,” Meg explained as she unwrapped a protective cap from the Army/Navy. The cap had a dense fake fur lining and ear flaps that tied under the chin with ribbons. Karen was under orders not to take it off for even a second. She was very blond, and you don’t want to flash white in the land of the whitetail. Blue eyes, red lips: the colors of a gobbler in breeding plumage. You need that safety orange. Karen put on the hat after school every day and wandered lonely as a cloud.

The Advent when she was a seven-year-old fifth grader, she found a toy she wanted.

She had walked for an hour, on the banks of shallow ponds and under thick hanging vines, through all the fields she knew and beyond, and she came out in an unfamiliar clearing. A hayfield with a barn, and tied out in front of the barn, a Welsh pony. There was a dirt road leading to the barn, both sides mown back three yards. The work of a busy and orderly farmer, but nobody around.

The pony looked at Karen. It was a roan in its winter coat. Its eyes were brown, with long white lashes, and it had little striped feet. She picked dandelion greens and arranged them in a pile on the grass. The pony stepped forward and ate.

To Karen’s mind, its acceptance of that minor consideration placed it under a contractual obligation to her. It was the middle of December, but she couldn’t imagine why a pony would be alone in the woods. To her it was plainly a lost pony, destined to be hers if she could tame it the way the boy did the Arabian in her favorite bedtime story, The Black Stallion . (Meg didn’t have the book, but she remembered the highlights.) It was tied to a piece of rebar in the ground and had a bucket of water, and the rebar moved around every couple of days, while the bucket was regularly refilled. Presumably it spent its nights in the barn, where its feed was very likely stored. But Karen was pushing eight years old and raised on poetry, so nothing in the world was clearer to her than that whoever first sat astride that pony would become its partner and master.

Still, she was a little child, not an idiot, so she regarded its substantial weight advantage, hooves, and teeth as potential risks. She was drawn to it by forces so strong she had not dreamed they existed, and repelled by caution so strong it was insurmountable. Which added up to: She hovered near it every day for an hour, staring. Over the course of a week and a half, she approached and touched it twice on the ribs, avoiding the reach of its kick and bite. She ran terrified when it turned to look at her. On Christmas Eve, it was gone.

She asked Meg in despair why a pony would disappear. Where did it go? Could mountain lions or timber rattlers have gotten it?

“It was probably some little girl’s Christmas present,” Meg said.

Karen had written to Santa asking for a banana split. She could find no words to express how Meg’s information made her feel. She trembled, aching with longing for something sweeter than sugar: money.

M eg’s financial situation was delicate. Her expenses were low. She had a thousand dollars of capital left in her emergency fund. If something worse than that came up, she’d cross that bridge when she got to it. She had no rent, no utility bills, and a daughter who could survive on a noodle a day. Karen ate dutifully, not with feeling. But sooner or later she was going to get her growth spurt and start liking food. And there was the little matter of clothing. The county had a thrift shop. Like thrift shops everywhere, it specialized in the leavings of the elderly dead. People always had acquaintances who needed children’s things and seldom donated them. Well-off children wore late-model hand-me-downs, but to get in on the action, Meg would have had to join a church. And although she was prepared to accept that the world was adopting stodginess as a fashion trend — that girls were putting away their mules and feather earrings and donning prim sweater sets like Lee’s mother — she could not face praising Jesus in song to put Karen in Pendleton kilts. You have to respect your boundaries.

Still, they needed clothes. Even polo shirts are born and die, in delicate pastels that show every stain. She needed an income.

Waitressing was out of the question. Waitresses are high-profile public figures. It doesn’t get any more visible than that. She might as well put her byline in the paper.

Cashier likewise, along with receptionist. Too public.

All jobs in the public eye: inadmissible.

As for invisible jobs, Meg pondered what they might be. Her mother, never a women’s libber, had steered her away from vocational education toward more disinterested studies in the liberal arts. Meg had met several working women in her years with Lee. She suspected that provost and sculptor, like latter-day Brontë, were not roles she could aspire to right off the bat.

Even the discreet and anonymous position of housemaid was a hard racket to break into. You need references. Someone has to tell everybody how discreet and anonymous you are. It was a conundrum. Plus, she was known around the county as black. She suspected herself of presenting a fatal attraction qua negress. Light-skinned, slim, unattached. If the men didn’t come to hate her, their wives would. The men would hate her for saying no, and their wives would never believe she hadn’t said yes.

She realized with some regret she had joined a race with which she’d had just about no contact at all. She had seen black people every day of her life. She wasn’t afraid of them. More like the reverse. But they might as well have been those Indonesian shadow puppets made of parchment. Her parents hadn’t had the option of sending her to an integrated school. If you integrated your school back then, the Commonwealth would shut it down. And although Stillwater had started admitting black girls a few years before she left, none had applied for admission — at least not that anybody knew of. Of course an applicant could be black and not know it. Possibly Stillwater had been integrated from the start. That was the standard defense of whites-only institutions: We’re not the DAR. We don’t check pedigrees.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу