My father was down by the place where Aeney had drowned. He was standing perfectly still, Huck beside him.

‘Dad?’

He only turned the second time I called. And when he did his face fell into that soft creased smile, but his eyes were the saddest I had ever seen them.

‘Hey, Dad. Hi.’

Maybe we all have momentary foreknowledge, which although of little practical use seals our hearts just enough to bear what’s coming. I turned to the river and saw the pages. Through the rain-mist of my glasses I saw them as white-caps. They were small, already distant, and sailing west in the swiftness of the current. I didn’t believe they were pages and then knew they were the poems, and knew the answer he was going to give me when I asked why.

‘They were no good, Ruth.’

I didn’t say anything. A better Ruth would have gone after them, a Ruth not afraid of the river. I stood silently by. I watched the poems go, and felt a laceration, which was partly my own but partly too my father’s, for I knew what throwing them into the river had cost him. I knew Abraham and the Reverend were right there. I knew he had failed the Impossible Standard and believed at that moment that everything he had done had been a failure. He had lost his son to the river, and then almost all of us in a fire that he was not even aware had been moving through the house while he had continued writing a poem he now considered useless.

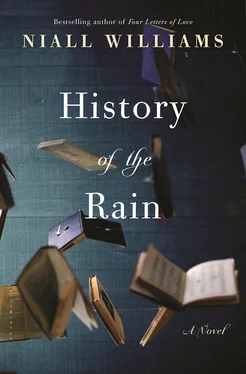

I think I knew then that a letter would come from London, that Mam would open it in the corner of Faha Post Office. That I would watch her read it and hear the sharp intake of her breath and then take the letter from her and read Dear Mrs Swain, we thank you for your letter. We are sorry to say we have no record of ever receiving History of the Rain.

We moved back in to our house. My father was hushed, like a man with ashes in his soul.

Eloquent in his own way, Father Tipp brought a set of Yeats left to him by a cousin in Tipperary who was unaware of his taste. These were the hardcover Mythologies, Autobiographies, Essays & Explorations and Collected Poems (Books 3,330, 3,331, 3,332 & 3,333, Macmillan, London), each of which I later discovered must to my father have had an air of peculiar prompting, because though they had gone elsewhere about the world on their inside flyleaves they bore stamps in green ink that said ‘Salisbury Library, Wiltshire’.

‘They need a finer mind than mine,’ the priest said.

My father took them with chin-tremble and head tilted to the ceiling to keep his eyes from spilling. Everything now was bigger than saying.

‘Thank you, Father,’ he said.

If wings could come they were coming then. In the three days that followed, while he sat in Aeney’s sky-room and read Yeats, my father was ascending.

On the third day I came home from school into the kitchen and called ‘Hello’ up to him. He did not answer. I climbed the Captain’s Ladder through the smells of fire and rain. I said, ‘Dad, I. .’

And that’s all I said, because there, at his desk under the skylight, in the pale gleam of the rain, my father was dead.

Taking you down.

That’s what the nurses say. Tomorrow, Ruth, we’ll be taking you down .

Mrs Merriman was taken down but she did not come back up. I have Mr Mackey so I am In Good Hands. I have said I don’t want details. I don’t want medical language. I don’t want a venous access device in here, or Interferon therapy or acetaminophen or arsenic trioxide or all-trans retinoic acid. I don’t want them in my pages. I want mine, like Shakespeare’s first folio, to be To the Great Variety of Readers, from the Most Able to Him that Can but Spell. (You kno who you ar.) I don’t want mine suffocated by science. I want mine to breathe, because books are living things, they have spines and smells and length of life, and from living some of them have tears and buckles and some stains.

Mrs Quinty has come up to Dublin. I told her not to, I told her when I was leaving there was no need, and that if you believe illness is everywhere the last place you should visit is a hospital. But that woman, though small, is irrepressible. She came into the ward like a short fat bird, buttoned coat, blue handbag and tighter-than-ever hairdo. Mam hugged her and Mrs Quinty said, ‘Don’t, I’m all wet,’ and then she looked at me and put a hand, flat, against her breastbone, pat, just like that, as though lidding what was open.

‘Dear Ruth,’ she said, and, after regaining herself, ‘Goodness. Do they not know how to fix up a pillow?’

Mrs Quinty brought the parish with her. She brought cards and well-wishes, news of candles and prayers, and then, mindful not to burden her visit with concern, recounted stories; Danny Devlin had taken his toilet out and thrown it in his front garden ahead of the toilet tax, said he’d knock his chimney ahead of the chimney tax, and brick in his windows before they came taxing daylight. (A country that understands the potency of imagery, the memory of our bankers, Mrs Quinty said, was to be enshrined in perpetuity in septic tanks.) Kevin Keogh, though he had about as much love for her as a small donkey, had surrendered at last and married Martina Morgan. The government, believing itself attuned to the pulse of the nation, had proposed abolishing the Senate, just as the Senate, Mikey Lucy said, were about to propose abolishing the government. Sean Connors had written from Melbourne and told his father he missed being with him at the silage, and in mute desolation Matt Connors had taken a poss of it, put it in a padded envelope and brought it to Mina Prendergast for posting, silage being for the Connors what the smell of coalsmoke was to Charles Dickens, and guava to Gabriel García Márquez, the indelible imprint of home.

All paradises are lost. The Council, Mrs Quinty said, has given up the ghost. The roads are going away. The windmills are coming. In the ghost estate, in disgust at the failures of promise, two of the Latvians have constructed an artificial paradise out of drugs and alcohol and raised a flag of Germany.

The river has continued to rise. It took the graveyard, left tombstones standing upright in the Shannon, then it came up Church Street for the church, and Mary Daly, who was still kneeling praying like in T.S. Eliot to the brown God, had to be ferried out just as she was starting to levitate or drown, depending on who was telling it. Our house, home to too many metaphors, had become metaphoric and needed a bailout. The McInerneys were at it.

‘You’ll only hear it from others so I might as well tell you,’ Mrs Quinty added, and pursed her lips and sat a little more erect to announce: ‘Mr Quinty has returned.’

The way she said it you knew she was still deciding what to do with him. Mam and I looked elsewhere.

‘Stomach ulcers,’ she said, with not entirely disguised pleasure, and left it at that.

Mrs Quinty is the only living person who read History of the Rain . When it was gone, and I asked her to remember it, she could not. Because of the haste, and the need to be undiscovered, the typing not the poems had taken her attention. She would touch her lip then put her hand out in front of her as if the words were coming, as if a speech bubble was forming, but no, she’d say, she would not do my father an injustice and give me a misremembered line.

In the white paperback of Yeats’s Selected Poems , beside ‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’, I read the two lines my father had written. Why did you take him? And Why does everything I do fail? And from those questions I understood Virgil Swain was applying the Impossible Standard to God.

I cannot say that my father had faith in God. The truth is that he had something more personal; he had a sense of Him, the Father of the Rain. The poems, the raptures and the despair I have come to think of as part of a dialogue; they were expressions of wonder and puzzlement, a longing for ascension and an attempt to make endure in this world a spirit of hope. So in my mind, day by day, the poems became greater for not existing.

Читать дальше