if you were M. Pujol, Madeleine says, I would reach out my hand to you. Like this. If you were M. Pujol, Adrien says, 1 would press my mouth against your pulse, like this. If you were he, she says, I would cup your dun in my fingers. If you were he, he says, I would take those fingers into my mouth. Then my mouth would envy my fingers, she says. Then your mouth must usurp your fingers, he says. And then, she says, I would do this.

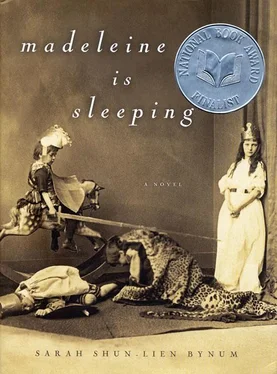

from her window, high above the world, the widow spots them the child and her photographer, entangled in the shadows of the shrubbery. And as she watches them, she feels the briefest flicker, like the singe of a match tip’s flame: quickly, now, before it’s gone! She tugs upon the bell rope that dangles beside her: a photograph must be taken; the moment must not be lost. Yes, here is the hind of her nighttime hunts; she has tracked it down at last. Then she laughs at herself, at the futility of her agitated summons. For how can he take the picture, when he is the picture? All of her efforts, if she is to be truthful, are marked by this same sense of impossibility. The more furiously she pursues, the more surely it recedes, this fugitive scene, visible only when glimpsed askance, out of the corner of her rheumy eye. Her latest project has been a failure; she had hoped that this marvelous invention, this alchemy of chemicals and light, would assist her in her pursuits, but now, as her eyes graze over the photographs, she discovers that they offer her nothing. And if they do, it is only by accident: in one picture, the fringe of the carpet is caught between the man’s toes; in another, the child’s mouth is open, as if she is about to speak: these are the details that prick her. But they are scarce among this series of tableaux, lovingly arranged, though ultimately of no poignance or excitement to her. Once she had been interviewed by a scientist, who was anxious to include a grandmother in his study of libertines, already several volumes long. He had amused her with the exacting nature of his questions, and his demands that she should include even the most scabrous details in her accounts. She had teased him, she couldn’t help it, so strenuous were his attempts to manage her perversions, to render them immobile. What you must finally recognize, she said, what you must understand about my predilections (the scientist leans forward: at long last, the secret!) is that my desire does not take; it turns, as milk does. For that reason, she feels only a litde sad when she finds, slipped beneath her door, a note written in an elegant hand: Please forgive me. I have left in search of a Faculty of Medicine who might take interest in my unusual condition. I plan to donate my body to Science, so that I can say my life has been of some use to Humankind.

but the child and her photographer are inconsolable. They cleave to each other as orphans do; they seek comfort in the photographs’ melancholy caress. Adrien has laid out all his pictures on the grass. This image, he tells Madeleine, is literally an emanation of M. Pujol: from his body radiates light, which then inscribes itself on the very surface which in turn your gaze now touches. They find solace only in the certainty that his body still touches them through the medium of light. But it is a solace that, the photographer knows, will lead slowly and inexorably to madness. The pictures before them serve not only as agonizing reminder of his absence but irrefutable proof that he did in fact exist for them, that his skin did burn upon the man’s fingertips, that his flesh did shrink from the girl’s stinging touch. This proof is what they cannot bear. He was indeed here, the photographs whisper. But he is no longer. A decision is reached, in the name of sanity. The widow finds beneath her door another note, much less elegantly penned. Two more of her assistants have decamped.

all the world is atremble: the dogs barking, the bells clanging, the fine white scent of orange blossoms everywhere, and Jean-Luc scuttling out the door before Mother can do anything about it. He is off to join the other boys, who are stealing enough copper pots and pans to deafen the whole town, when tonight they go marching through the streets, banging and hallooing till the dawn. It is in this moment of confusion, with every child in motion around her, the girls leaning out the windows, waving, and the boys snatching up her spoons, that Mother looks at Madeleine. How still she is, how quiedy she sleeps. Her breathing barely lifts the covers. She is so beautiful when she sleeps. The children stop. They stare at their mother. They have not heard this said in a very long while. Smooth your sister’s coverlet. Arrange her hair on the pillowcase. And Mother gazes at the girl with a calm affection, as if their silent quarrels were now coming to an end, as if that lush and troublesome body had been restored, by miracle, to its former beauty and perfection. Outside, the church bells cease their clamor. On the stone steps leading down from the chapel, a bride and groom stand blinking stupidly in the sunlight. Why did I never think of it before? Mother wonders.

the two travellers, sheltering beneath a chestnut tree, are startled by a crashing, a harried thrashing, from above. It is Mme. Cochon, struggling to free herself from the embrace of an amorous upper branch. Her dainty wings churn the air, her stout legs kick furiously, and from a neighboring tree, a wild cloud of sparrows rises up in sisterly agitation. Mme. Cochon! cries Madeleine, whose earthbound perspective grants her insight into the situation. Your skirts! They are caught! The enormous woman heaves herself over so that she can unlatch her hem from the tree. Oh, bother, she gasps, this is always happening. Madeleine, in her excitement, treads upon the photographer’s toes. A face from home! It has been so long. She trots backwards and beams up at the woman, whose buttocks bob among the leaves like the hull of a capsized ship. With a crackling of twigs and a fluttering of wings, Mme. Cochon pulls herself upright. She calls down to Madeleine, Your mother doesn’t know what to make of you! The girl grins back at her: She never did! Adrien tugs at Madeleine’s sleeve: he hopes to take advantage of the fat woman’s surprising appendages. From up there, she can see the entire world, or at least a sizeable portion of it. Mme. Cochon! Madeleine hurls her voice at the sky. Have you seen a tall and pale-faced man pass this way? Carrying a porcelain basin, a length of rubber tubing, a silver candlestick, and a small family of flutes? You would have noticed his elegant costume; he dresses beautifully, no matter what time of day. The fat woman sails upward, always happy to oblige. The two travellers wait below, his hand clasping her paw. A black tailcoat? Mme. Cochon hollers. Satin breeches ruched at the knee? Oh yes! That’s him! The woman, high above them, points towards the horizon: He is headed for the hospital at Maryville.

rising up from behind a hill, the hospital at Maryville has as many windows as it does patients; its hundred eyes glitter in the morning sun. For every patient, a window, floating high above his head — too high out of which to climb, or even to gaze. When passing by the hospital, one never sees a crazy face pressed against the pane. One is never made aware of the hundred lives contained within. Yet the feeling persists that the building, so modern and brick and glittering with glass, is animated by a peculiar intelligence, and that while the rest of the world is sleeping, at least one of those eyes is still open, and wakeful, and watching. The hospital eschews all reminders of its past. Do not call it the madhouse, or the lunatic asylum. All that was once dark and hidden and misshapen is now frankly examined in the light that comes streaming, unchecked, through these flashing windows. It is the Institute for the Study of Aberrant Behaviors and Conditions. When Madeleine rings at the front gate, a ruddy, uniformed matron appears, bringing with her the smell of laundry soap, square meals, sanitary practices. Her glance takes in the girl, the photographer, the little wagon brimming with canisters and bellows and bulbs. She spies the crippled hands. Come in, the matron says. Come in.

Читать дальше