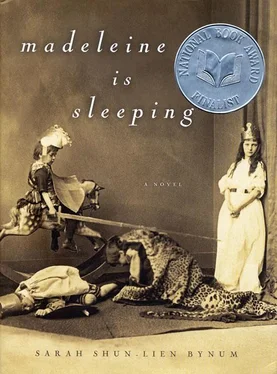

Sarah Bynum - Madeleine Is Sleeping

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Sarah Bynum - Madeleine Is Sleeping» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Harcourt, Inc, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Madeleine Is Sleeping

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harcourt, Inc

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Madeleine Is Sleeping: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Madeleine Is Sleeping»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Madeleine Is Sleeping — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Madeleine Is Sleeping», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

tell me

you must see, the photographer pleads. You must see how you are — compromising— His hands fly up from his pockets, fluttering with urgency, making all the arguments that language has failed to provide him with. Madeleine notes this carefully, the articulateness of his hands. He has become, quite suddenly, interesting to hen She grows shy in his presence. She is curious about everything he does. Wrecking? Madeleine asks, as his hands wring the air. Destroying? Together they stand at the edge of the lawn. She is spreading,1 her newly washed drawers across the privet hedge to dry. How white they appear against the green, looking as if they might rise g up at any moment, like sails, and pull with them the privet hedge, I the velvety lawns, the grand house with its carpets and curtains. | Only a great gust of wind is needed, and all will be unmoored. Madeleine must concentrate on this, the white against the green, so as not to gaze too long at the photographer’s face, or his talkative hands. Yes, Adrien admits, exhausted. You are destroying everything. He means that the widow is unhappy. She is unhappy because the girl continues to refuse her. Every night, they gather in her drawing room; every night, the candles are lit, the tripod’s spindly legs are spread, the performers are placed in their humiliating poses; every night, the girl lifts her paddle (his cheek, her hand, smack! was the sound) and freezes. Madeleine nods, pretends to listen. She would like to be having a different conversation. She would like to ask, Do you chew anise seeds? And is that you I hear sometimes, singing beneath your breath? Maybe they could take a turn around the garden. Maybe he could invite her inside, for a drink of water. What gives your shirts their nice smell? She wants to say, Tell me. She wants to know. Was it like—? Did you feel—? She will send us away, the photographer says.

taste

special delivery! Mother sings out, clutching a jar in each of h hands. But the mayor opens his door no more than a crack. Mother smiles at him shyly. It’s pear, she says. Your favorite. The crack widens by a hair. Madame, the mayor begins, I am a supporter of local business— Indeed you are! she cries. Last month you bought a dozen jars! And presenting her gifts, she says, Do not think I have forgotten. The door creeps farther open, then closes with a slam. Mother stumbles backwards. She stares at the mayor’s front door; she frowns at this most uncivic display. The red door swings open once again. The mayor has been replaced by his sour-faced daughter, her jaw set, hejr feet planted. Old enough, Mother thinks, to be married by now, and bullying someone other than her father. Good morning, Mother ventures. What do you want? the daughter replies. To leave a token, Mother says, of my appreciation for the mayor. And she holds up each golden specimen for her to see. Preserves! the daughter snorts. Just as I thought! She folds her arms across her narrow chest: We are not interested. The things you make — they have a queer taste. Mother, looking in dismay at her jars, cannot muster a reply. The mayor’s daughter takes advantage. She observes, as she closes for the last time the door, But why should you care whether we like your preserves? You have so many customers in Paris.

naps

the flatulent man is very tired. His pale face has turned grey. Two dark circles seep from beneath his eyes, like drops of ink dissolving in a bowl of milk. It is necessary now to take naps. Every afternoon he goes off hunting for them. Sometimes he is lucky: once, behind the gatehouse, in a cool damp spot that smelled of clay; another time, in a corner of the kitchen garden, abandoned to the eggplants. He creeps up on these places. He makes himself thin as a shadow. When he wakes, he expects to find himself squinting into the sun. He expects that a long afternoon has passed, that the sun has moved across the sky and found him, its light slanting across his ” face, staining the inside of his eyelids. So he is surprised, when he wakes, to discover himself still in shadow, to see only the green sweating flagstone of the gatehouse, its surface alive with insects; or the dark, hairy depths of the tomato vines. And when he draws himself up onto his elbows, he will often hear a rustling, will catch a glimpse of white stocking disappearing into the foliage, or the flash of a silver watch chain. He wants to cry out, Wait! But the two are doe-like creatures; they seek him out and stare, then flee, their white tails showing. They spring off into the underbrush, off to their quarrels, their little anxious tasks, their acts of love, before he can stop them and say: At night, with the gravel rattling overhead — I have difficulty sleeping.

poem

looking at him, the man asleep in the garden, Adrien says, One time I touched his face. Madeleine, at his elbow, finds her eyes watering at the thought of this. He offers her the nice-smelling sleeve of his shirt. Can you see? he asks, pushing aside a branch, pushing the hair from her face. The sight makes her suffer. There he is, her enemy, on the ground as if dead: he who has, without knowing, without even trying, replaced her in her own affections. This makes the concession all the more galling to her, this unconsciousness. Yet the beauty of him asleep, arm thrown out, mouth open — if only she knew a poem! If only her hands and fingers could speak for her, making eloquent shapes in the air as Adrien’s do. It is with one of these fingers that he tucks a piece of hair behind her ear. She turns to him, full of speech. But her hands are struck dumb, and the only words that occur to her are: Orchard. Swallow. Bell.

mise en scene

M. pujol knows what he will find when he opens the drawing, room door. He pictures it with the same sense of misgiving with which he recalls the schoolroom he sat in when he was a child, the map he had drawn of its dangers and unfriendly territories: the desk with an obscene picture on its lid; the alcove where the strongest boys hatched their plots; the row of meek children who would look at him knowingly, as if he belonged to them; the chair with the mysterious words scratched under its seat, over the ridges of which he would trace his fingers helplessly, and then pull his hands away in self-disgust, feeling contaminated. He had been glad, as a child, to be taken from that schoolroom. It was all thanks to his unusual gift. But what now could deliver him? Deliver him from the constellation of widow, girl, photographer, one perched on the edge of her delicate chair, one waiting at attention on the carpet, one crouched behind his camera, making the whole contraption tremble with his hunger. In a corner of the drawing room stands an Oriental screen, behind which he will be asked to take off his clothes. In another corner is a small bust of Racine. In the window seat is Marguerite, pouring lotion from a bottle into the thick palm of her hand. And crowded against each other, limbs and haunches bumping, like statuary forgotten in a warehouse, are the acrobats, the emaciated man, the dog girl, and the stringed woman, each body arranged to tell its own story.

knight

if he declined to open the door, if he refused to enter — would that be cowardly or brave? Trusting habit, he should think himself a coward. But when he stands outside the drawing-room door, his damp forehead resting against the frame, he discovers that what he fears most is not his own humiliation, which he has grown used to, but rather the fury that will be unleashed upon the girl. And to rescue her — that would be a brave thing. What a brave thing! For the girl, in her stubbornness, is met every night with glowering looks, and pinches, and the thump of the acrobats as they collapse accusingly onto the carpet. Sometimes Marguerite rises up from die window seat and strikes her. As for the widow, she never shows her displeasure, but the very restraint with which she leaves the room makes him afraid. He could save her from this, he thinks, by his absence. It would be as simple as leaving. As simple as airing out his travelling case, folding his evening clothes in tissue paper, sliding his shoes into their little felt bags, putting his brushes in order. How easy and how courageous it would be, to leave. He imagines how the gravel will crunch underfoot, the feel of his case bumping against his side. A flying leap! An adventure! But where to? That he will consider later. For now, as he nods to Racine, as he disappears behind the Oriental screen, his fingers already loosening his white evening tie, he will think only of the felted bags, soft and grey and consoling as the moles he sometimes finds outside his door, in the mornings.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Madeleine Is Sleeping»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Madeleine Is Sleeping» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Madeleine Is Sleeping» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.