“There's coffee in the kitchen,” I said. “It's still hot.”

When he returned with the coffee he came all the way into the room and stood in front of me. He seemed disconcerted.

“I think I'll go check out that old foundry today,” he said. “There's some wrecked equipment I always wanted to take pictures of.”

“No camera,” I reminded him.

“Well, I guess I'll just go look at it.”

Ruins, I thought. Wrecks, shambles, margins. Zen junk.

“That's fine, I'll be here,” I said. “I have some stuff to do. We can go out for dinner tonight.”

“We could cook something,” he began. I could see him grasping, trying to frame some larger question.

“I'd like to take you out,” I said — magnanimity being one of the most effective ways of ending conversations. I was thinking of my work. I had to get back to harnessing our high-school sensibility to the task of selling compact discs.

HE WAS back at five, with another bag from the Piggly Wiggly. Inside was a full six-pack, and another one full of empties. He'd been out all day looking at sites and drinking beer from a paper bag. He put the empties on the porch and the six in the fridge, like an obedient dog moving slippers to the bedroom.

I'd arranged for us to meet a couple of friends for dinner. A science-fiction writer who does scenarios for interactive video games, and a screenwriter. We all have the same Hollywood agent, which is how we met. I figured the screenwriter could sober Matthew up about his script ideas. I didn't want to eat dinner with Matthew alone anyway.

We met for drinks first. By the time we got to the restaurant Matthew was lagging behind, already so invisible that the maître d' said, “Table for three?”

He barely spoke during dinner. At the end of the night we parted at my driveway, me to my front door, Matthew to the garage.

“Well, good night,” I said.

He stopped. “You know, I realize I don't have everything quite together,” he said.

“You've got a lot of interesting projects going,” I said.

“I'm not asking you for anything.” He glared, just briefly.

“Of course not.”

“I feel strange around you,” he said. “I can't explain.” He looked at his hands, held them up against the light of the moon.

“You're just getting used to the way I am now,” I said. “I've changed.”

“No, it's me,” he said.

“Get some sleep,” I said.

I didn't see him in the morning, just heard the shower running, and the door to the refrigerator opening and closing.

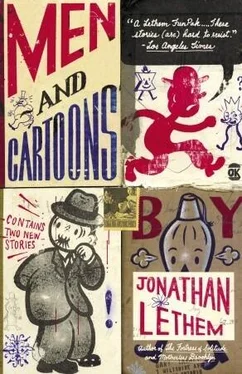

ABOUT A week later, I hit on the idea of putting Matthew into Planet Big Zero as a character. It was a way of assuaging my own guilt, and of compartmentalizing the experience of seeing him again. I guess I also wanted to establish the connection between our old wide-open, searching form of humor and my current smug, essentially closed form.

As I drew Matthew into the panels it occurred to me that I was casting him into a prison by publishing him in the cartoon. Then I realized how silly that was. If he was in a prison he was there already, and the cartoon had nothing to do with it. He'd be delighted to see himself. I imagined showing it to him. Then I realized I wouldn't. Anyway, I finished the cartoon, and FedExed it to my editor.

Who hated it. “What's that guy doing there?” he said on the phone.

“He's a new character,” I said.

“He's not funny,” said the editor. “Can you take him out?”

“You want me to take him out?”

“He's not intrinsic to any of the scenes,” said my editor. “He's just standing around.”

THAT WAS two months ago. The point is, it wasn't until just the other day, when I hit the sleeping bum on the head with the gate, that I really gave any thought to the way things turned out. So much of what we do is automatic, so much of life becomes invisible. For instance, I've been buying six-packs and putting them in the fridge, but it isn't me drinking them. The empties pile up on the porch. I always forget to bring them out to the curb on recycling day. Sometimes the bums prowl around for bottles and do my work for me. I think somebody somewhere gives them a nickel apiece for them — another invisible operation, among so many.

Matthew's parents' car got towed after two weeks. It must have had ten or fifteen tickets pinned under the wiper. The authorities are pretty vigilant about that around here. As for Matthew, he's still in the garage. But he's been rendered completely transparent, unless, I suppose, you happen to be wearing Toscanini's glasses.

ROWS OF FRAMES SAT ON GLASS SHELVES, clear lenses reflecting gray light from the Brooklyn avenue. Outside, rain fell. At the door a cardboard box waited for umbrellas. The carpet was pink and yellow, to the limits of the floor, to the tightly seamed glass cases. The empty shop was like a cartoonist's eyeball workshop, hundreds of bare outlines yearning for pupils, for voices. They fell short of expression themselves. The whole shop fell short. There was no radio. The white-coated opticians leaned on their glass counters, dreaming of their wives, of beautiful women who needed glasses. One of them moved into the rear of the shop and made a call.

The other turned as the door chimed, two notes blurred momentarily in the rain's hiss.

“You're back.”

“Damn fucking right I'm back.” The black man wiped his feet just inside the door, though there wasn't a mat, then jogged forward into the shop. He wore a baseball cap, and his glasses.

The optician didn't move. “You don't need to use language,” he said.

They'd sold him his glasses yesterday. One hundred dollars. He'd paid with cash, not out of a wallet.

The customer bounced from one foot to the other like a boxer. An ingrown beard scarred the underside of his long jaw. He pushed his chin forward, keeping his hands by his side. “Look. Same damn thing.”

The optician grunted slightly and moved to look. He was as tall as the customer, and fatter. “A smudge,” he said.

He was still purring in his boredom. This distraction hadn't persuaded him yet that it would become an event, a real dent in the afternoon.

“ Scratched ,” said the customer. “Same as the last pair. If you can't fix the problem why'd you sell me the damn glasses?”

“A smudge,” said the optician. “Clean it off. Here.”

The customer ducked backward. “Keep off. Don't fool with me. Can't clean it off. They're already messed up. Like the old ones. They're all messed up .”

“Let me see,” said the optician.

“Where's Dr. Bucket? I want to talk to the doctor.”

“ Burkhardt . And he's not a doctor. Let me see.” The optician drew in his stomach, adjusted his own glasses.

“ You're not the doctor, man.” The customer danced away recklessly, still thrusting out his chin.

“We're both the same,” said the optician wearily. “We make glasses. Let me see.”

The second optician came out of the back, smoothed his hair, and said, “What?”

“Bucket!”

The second optician looked at the first, then turned to the customer. “Something wrong with the glasses?”

“Same thing as yesterday. Same place. Look.” Checking his agitation, he stripped his glasses off with his right hand and offered them to the second optician.

“First of all, you should take them off with two hands, like I showed you,” said the second optician. He pinched the glasses at the two hinges, demonstrating. Then he turned them and raised them to his own face.

The inside of the lenses were marked, low and close to the nose.

“You touched them. That's the problem.”

“No.”

“Of course you did. That's fingerprints.”

Читать дальше