THE START OF THE AXLETREE

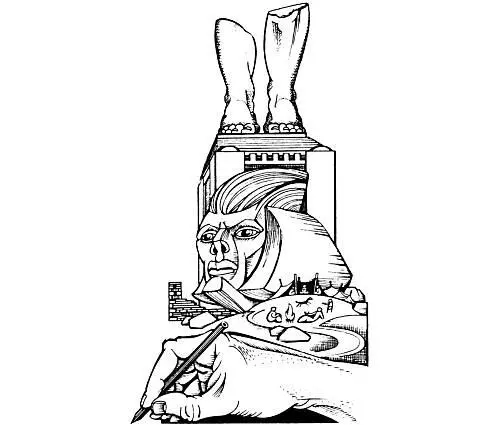

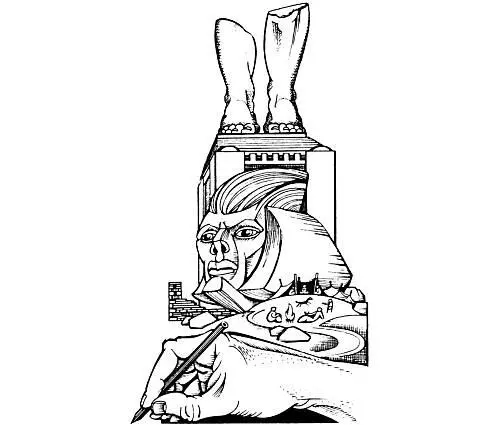

I write for those who know my language. If you possess that divine knowledge do not die without teaching it to someone else. Make copies of this history, give one to anybody who can read it and read it aloud to whoever will listen. Do not be discouraged if they laugh and call you a liar. Perhaps they are dull herdsmen who think milk and wool more important than history. Their own history is a tangle of superstition and confused rumours. Those who lived inside the great wheel used to call them the perimeter tribes. “Were you born outside the rim?” we would ask someone who was acting stupidly or strangely and this question was a grave insult. The perimeter tribes lived so far from the hub that they only saw the axletree for a few months before it was completed and then only on unusually clear days. Even at sunrise its shadow never quite touched them, so now they say it was the last impiety of a mad civilization, an attack upon heavenly god which provoked instant punishment and defeat. But the axletree was a necessary inevitable work, soberly designed and carefully erected by statesmen, bankers, priests and wise men whose professional names make no sense nowadays. And they completed the axletree as intended. For a moment the wheel of the civilized world was joined to the wheel of heaven. The disaster which fell a moment later was an accident nobody could have foreseen or prevented. I am the only living witness to this fact. I have been higher than anybody in the world. The hand which writes these words has stroked the ice-smooth, slightly-rippled, blue lucid ceiling which held up the moon.

I was born and educated at the hub of the last and greatest world empire. We had once been a republic of small farmers in a land between two lakes. Our only town in those days was a walled market with a temple in the middle where we stored the spare corn. Our land was fertile so we developed the military virtues, first to protect our crops from neighbours, then to protect our merchants when they traded with the grain surplus. We were also the first people to shoe horses with iron, so we soon conquered the lands round about.

Conquest is not a difficult thing — most countries have a spell of it — but an empire is only kept by careful organization and we were good at that. We taxed the defeated people with the help of their traditional rulers, who wielded more power with our support than they could without, but the empire was mainly held by our talent for large-scale building. Captains in the army were all practical architects, and private soldiers dug ditches and built walls as steadily as they attacked the enemy under a good commander. The garrisons on foreign soil were built with stores and markets where local merchants and craftsmen could ply their trade in safety, so they became centres of prosperous new cities. But our most important buildings were roads. All garrison towns and forts were connected by well-founded roads going straight across marsh and river by dyke and viaduct to the capital city. In two centuries these roads, radiating like spokes from a hub, were on the way to embracing the known world.

It was then we started calling our empire the great wheel. Surveyors noted that the roads tended to rise the further from the capital they got, which showed that our city was in the centre of a continent shaped like a dish. It became common for our politicians to start a speech by saying This bowl of empire under this dome of heaven … and end by saying We have fought uphill all the way. We shall fight on till we reach the rim . This rhetorical model of the universe became very popular, though educated people knew that the hollow continent was a large dent in the surface of a globe, a globe hanging in the centre of several hollow globes, mainly transparent, which supported the bodies of the moon, sun, planets and stars.

The republic was controlled by a few rich families who worked in the middle of an elected senate, but one day it became clear that whoever commanded the army did not need the support of anyone else. A successful general proclaimed himself emperor. He was an efficient man with good advisers. He constructed a civil service which worked so well that trade kept flowing and the empire expanding during the reign of his son, who seems to have been a criminal lunatic who did nothing but feed his worst appetites in the most expensive ways possible. It is hard to believe that records tell the truth about this man. He was despised by the puritan aristocracy who filled the civil service, but loved by common citizens. Perhaps his insane spending sprees and colossal sporting events were devised to entertain them. He also obtained remarkable tutors for his son, men of low and foreign birth but international fame. They had made a science out of history, which till then had been a branch of literature. When their pupil became third emperor he knew why his land was heading for disaster.

Many nations before ours had swelled into empires. Nearly all had collapsed while trying to defeat a country, sometimes a small one, beyond the limit of their powers. The rest had enclosed the known world and then, with nothing else to conquer, had gone bad at the centre and cracked up through civil war. The emperor knew his own empire had reached a moment of ripeness. It filled the hollow continent to the rim. His roads touched the northern forests and mountains, the shores of the western sea, the baking southern desert and the wild eastern plains. The perimeter tribes lived in these places but we could not civilize them. They were nomads who could retreat forever before our army and return to their old pasture when it went away. Clearly the empire had reached its limit. The wealth of all civilization was flowing into a city with no more wars to fight. The military virtues began to look foolish. The governing classes were experimenting with unhealthy pleasures. Meanwhile the emperor enlarged the circus games begun by his father in which the unemployed poor of the capital were entertained by unemployable slaves killing each other in large quantities. He also ordered from the merchants huge supplies of stone, timber and iron. The hub of the great wheel (he said) would be completely rebuilt in a grander style than ever before.

But he knew these measures could only hold the state for a short time.

A few years earlier there had appeared in our markets some pottery and cloth of such smooth, delicate, transparent texture that nobody knew how they were made. They had been brought from the eastern plains by nomads who obtained them, at fourth or fifth hand, from other nomads as barbarous as themselves. Enquiries produced nothing but rumour, rumour of an empire beyond so great a tract of desert, forest and mountain that it was on the far side of the globe. If rumours were true this empire was vast, rich, peaceful, and had existed for thousands of years. When the third emperor came to power his first official act was to make ambassadors of his tutors and send them off with a strong expeditionary force to investigate the matter. Seven years passed before the embassy returned. It had shrunk to one old exhausted historian and a strange foreign servant without lids on his eyes — he shut them by making them too narrow to see through. The old man carried a letter to our emperor written in a very strange script, and he translated it.

THE EMPEROR OF THREE-RIVER KINGDOM GREETS THE EMPEROR OF THE GREAT WHEEL. I can talk to you as a friend because we are not neighbours. The distance between our lands is too great for me to fear your army.

Читать дальше