This was a wholly serious experiment, but it was taken more as a postmodernist joke, grasped in terms of its metaphorics rather than its physics. Physicists don’t read novels. Which disappointed me greatly and caused me to withdraw from publishing for a decade or so.

Here’s what I’m interested in now. Can going back in time by recalling everything down to the last detail, with all senses engaged, bring about a critical point? Can it flip some switch and cause the whole machinery of the Universe to start going backward? It’s on the edge in any case, so the only redemptive move is backward. Minute by minute, during this hour everything that was an hour ago will happen. The entirety of today is replaced by yesterday, yesterday by the day before, and so on and so forth further and further back, we slowly step away from the edge with a creak. I don’t know whether we can meddle in those impending past days. We’ll have to relive our prior failures and depressions, but also a few happy minutes among them. There’s no getting around.

. the new injustice of death. Those, who at the moment of the reversal had already lived eighty years, will live another eighty, backward. Those who had lived not as long, say thirty, forty, or fifty years, will have to be satisfied with that same amount. But let’s note that they will be heading toward their own youth and childhood. Ever happier at the end of their lives, ever younger, ever more adored. Happily wobbling on their unsteady little toddler’s feet, having forgotten language, cooing and gurgling, until the day comes for them to go back home. Thus, I, born on January 1, 1968, will be able to die again on January 1, 1968. That’s what I call complete universal harmony. To die the hour and minute you were born, after passing through your whole life twice. From one end to the other and back again.

G. G.

January 1, 1968—January 1, 1968

Lived happily for 150 years.

(Everyone can insert their own name and date here.)

They claim that life arose on earth three billion years ago. With this mechanism, we can guarantee at least three billion more years of life. If someone else has a better offer, then be my guest.

Another gravity is pressing in on us, one not found in classical physics, one which must be overcome, the gravity of time. That gravitational delay, which Einstein described back in 1915, doesn’t work for me. In 1976 NASA confirmed that in the microgravity of space, time really does slow down a teeny bit, and this gave rise to the legend that people don’t age in space. The myth of eternal youth was again on its way to being revived. A dozen or so aging millionaire matrons must’ve glanced up at the sky as if toward an eternal sanatorium, calculating how much a stay there with their beloved fox terriers would cost, because what’s.

. the point of being young if your pooch is pushing up daisies? This legend even reached us, I remember it vaguely, but being all of eight years old I hardly paid any attention to it. In 2010, they actually measured that time lapse with an interferometer. Yes, there was a slowing of the cesium atom (that’s what they used), but it was insignificantly small — over a few billion years there’s a delay of a hundredth of a second. Those who had hoped to stay forever young in 1976 surely hadn’t lived to see this highly disappointing result.

My goal isn’t to slow time by a few hundredths of a second over a billion years, which I don’t have at my disposal in any case. And not in outer space, which I have no particular soft spot for (even the bus makes me car sick). I want to bring back a slice of the past, a pint of drained-away time right here, within the confines of one insultingly short human life.

NEW EXPERIMENTS

I practice concentrated and close “observation.” I realized relatively early on that the shorter the time period I want to recreate (replicate), the better my chances. I gave up on the idea of my whole childhood. For some time I tried one chosen year. To remember that year in detail, to reconstruct it personally and historically, leaving nothing out.

I picked the year of my birth, because the infant has a more limited and pure world, which in that sense is easier to reconstruct, with fewer extraneous noises. So here’s the new 1968. By happy coincidence, I was born in its first days, so the two stories, mine, small and piss-soaked, and its, grand (and also piss-soaked), could unfold in parallel. The wet cloth diapers, the January cold, my mother’s warm skin, the first signs of spring in the Latin Quarter, nighttime colic, summer in Prague, the international youth festival in Sofia, “brotherly” troops in Czechoslovakia, first tooth. Everything was important. After a few months I was lying on the floor exhausted, crushed by the world’s entropy. I realized that it was beyond my strength and stamina to build — as if from matchboxes — a year in its real dimensions with all of its scents, sounds, cats, rain, and newsworthy events. I’ve kept the draft of that failed experiment.

I need to narrow the range of the experiment. I decided on a month from another year, August 1986, I’m eighteen, my last month of freedom, after which my mandatory military service awaits me. A month, in which you say farewell to everything for two years — actually for forever, but you don’t know that then. You let your hair grow long, you try to get to home base with your girl. Late at night, when your parents are asleep, you sneak out with a friend into the city’s empty streets, you go to the river and look at the dark windows of the panel-block apartment buildings, on the verge of yelling “Sleep tight, ya morons!” à la Holden Caulfield or whatever it was he said.

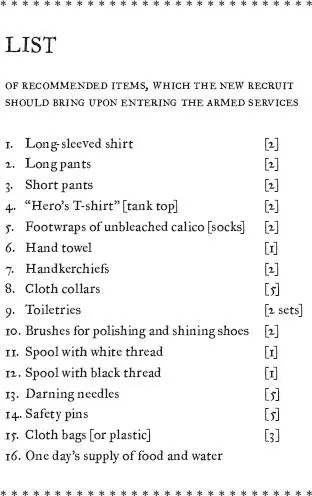

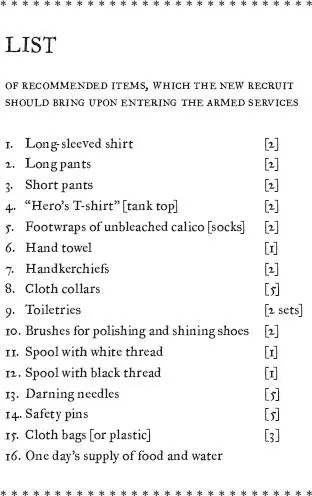

. but in the end you don’t do it. At the end of the month you go to the barbershop farthest away to get a buzz cut. You watch your hair falling to the floor and you try not to start bawling. You leave the barbershop already a different age, crestfallen, freaked out, sporting the hat you had prepared in advance, and you take the shortest route home. A few days later you’ll have to show up at the appointed place in some strange city — with a shaved head and a bag filled with all the things from the list of what a recruit needs. I’ve kept that list in one of the boxes.

That was more or less the month from which I needed to reconstruct every moment and sensation with all of their subtlest oscillations. It wasn’t so easy. Yes, there was fear during that month, but it was thousands of variations on fear, in some of them it looked like a radical dose of daring. Yes, there was sorrow, but the atoms of this sorrow moved quite freely and chaotically (sorrow’s state of aggregation is gaseous) and in the best-case scenario I could only follow its twists and turns, the smoke that smoldered nearby. I lit up my first cigarettes, I now realize, to give a body to this sorrow, bluish, light-gray, vanishing. I remembered everything clearly, but I couldn’t manage to get back into that former body. What I used to be able to do — entering into different bodies and stories with the ease of a man entering his own home — now turned out to be out of reach.

EPIPHANIES

It happened when I least expected it.

It was a late winter afternoon, the snow was melting. A few days before I completely stopped leaving the basement. I was walking ever more slowly, looking at the houses, the Sunday’s empty streets, January. It occurred to me, for the first time with such clarity (the clarity of the January air) that what remains are not the exceptional moments, not the events, but precisely the nothingeverhappens. Time, freed from the claim to exceptionality. Memories of afternoons, during which nothing happened. Nothing but life, in all its fullness. The faint scent of wood smoke, the droplets, the sense of solitude, the silence, the creaking of snow beneath your feet, the vague uneasiness as twilight falls, slowly and irreversibly.

Читать дальше