My father, said Tipura, was born in 1929, and he grew up with a foster family, because his mother entrusted him to a foster family because his mother was only fifteen when she agreed, on 31 December, 1928, to go to the flat of a waiter who worked at a café at the hippodrome, a great aficionado of horse races, a fanatic gambler, who would, nine months later, become the biological father of my father, Norbert, said Tipura. As an adult, my father, too, became a fanatic gambler, a fixture at the horse races, I don’t know how that happened, said Tipura, but now I, too, love horses and horse racing. My father, said Tipura, became head of the Munich branch of the Hitlerjugend, at home he had a large world map hanging on the kitchen wall and he pinned flags on it whenever the German troops, the Wehrmacht troops, captured a town, a region, a country, which then lost its name and became Germany. When the war ended, my father saw 1945 as a year of crushing defeat, rather than a year of victory. I was young, my father would later say, Tipura told me, and he often repeated, Lord, what would I have become had Nazism prevailed. But he did not dig deep, he never dug into the family shit, he only poked at it, smeared it around, said Tipura. His portraits of the children of Nazis are almost nostalgic flashes of the past, tender portrayals of helpless victims. And so, when I found my father’s notebook, I set out on my own exculpatory journey, I looked for the same “children”, for the ones my father spoke to forty years earlier, and I found elderly people clutching well-worn bundles of family history, bundles they baulk at unpacking, and when they do, everything inside is greyness.

Martin Bormann Junior (a.k.a. Kronzi) was born in 1930, the first of ten children of S.S.-Obergruppenführer Martin Bormann, head of the National Socialist Party Chancellery and Hitler’s private secretary, a stocky, muscular watchdog at the entrance to the Machiavellian Third Reich Hades, a hater of Christian churches, the fiercest anti-cleric among the Nazi officials, the man who sparked the Kirchenkampf, who committed cowardly suicide in 1945, biting into a cyanide capsule after he had been wounded while fleeing Adolf’s bunker. There is no help for Martin Bormann Junior, a dedicated young Nazi from 1940 to 1945, attending the Party Academy in Bavaria, who after the war embraces the Catholic faith and becomes a priest, so that he can repent the sins of his father, sins which spun around his body everlasting fibres, leaving him, Martin Bormann Junior, languishing for years like a squished caterpillar in a dark cocoon. Martin Bormann Junior is not helped by God or the Church or the fucking Our Father or “our trespasses, our trespasses”, which he mutters into his beard. So after several wasted decades he bids the Church auf Wiedersehen! and marries a former nun who has also told the Church addio, bye bye, and the two of them start making the rounds of German and Austrian schools, where they tell children of the horrors of the Holocaust and the Third Reich. Then they go to Israel and bow to the victims of Martin Bormann Senior, and in so doing, coexist with the ghosts who sit at their table and crawl into their bed. Martin Bormann Junior told me he remembers the furniture and decorative lamps made of human bones and skin in the home of Himmler’s mistress Hedwig Potthast, Tipura said. Bormann Junior does what he can to cure himself, Tipura said, but his sister Irmgard burns in her own hell, blinded by the flames of her diseased love for her “good and tender father, whom she would love and respect to her death ”, Tipura said.

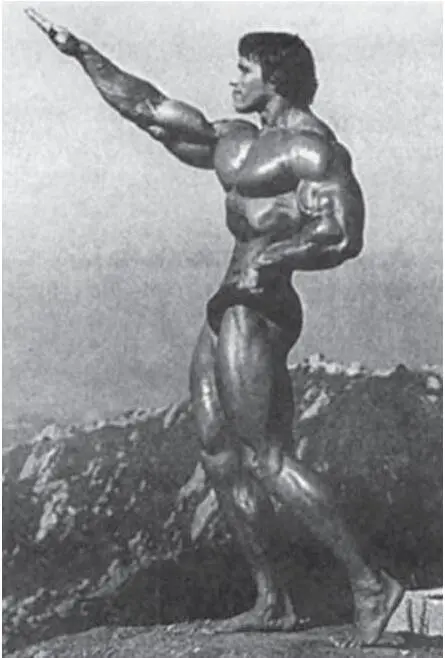

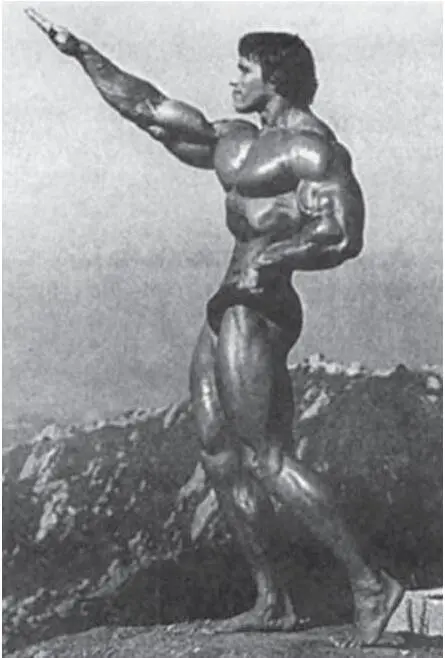

Arnold Schwarzenegger’s father was a Nazi , Tipura said. Gustav Schwarzenegger asked to join the National Socialist Party as early as 1938, before the annexation of Austria, but it was only in 1941 that the National Socialist Party drew him to its bosom. In his medical records from the time, one can read, Tipura told me, that Gustav Schwarzenegger was a quiet and reliable person, a person of average intelligence, not remarkable for anything in particular. From 1947 until he retires, Schwarzenegger works as a policeman — since, they say, he committed no war crimes. Arnold, however, during a time of peace and blessed Austrian forgetfulness, develops his physique by lifting weights, and in 1967, when he is twenty and before he becomes the Terminator, he wins the title of Mister Universe and looks like this:

Today Schwarzenegger, who did not consent to speak with me, Tipura told me, today Schwarzenegger says, My father was an ordinary soldier in the army of his country. My father fought in Belgium and in France and in Russia, and it is known, Schwarzenegger says, that my father did not commit a single crime, because the soldiers of the Wehrmacht did not kill, the soldiers of the Wehrmacht merely waged war, says Schwarzenegger who probably did not attend the Wehrmacht exhibition, said Tipura, because had he attended the Wehrmacht exhibition he would have seen that even the ordinary German soldiers of the Third Reich committed appalling crimes, which was an insight that stunned the German public then, at that Wehrmacht exhibition, and perhaps that insight would have stunned him, Arnold Schwarzenegger, as well, said Tipura.

I didn’t need Tipura. I could have done without his stories and his discoveries. By 2000 I had amassed my own file of the “case histories” of Nazi descendants, the descendants of the first, second and third generation of Nazis, big and little, known and anonymous, regardless, the symptoms are more or less the same, and my file kept growing, getting fatter like a goose I was ruthlessly fattening until it keeled over. In nearly every case I studied there was a similar pattern: the children and grandchildren of Nazis rarely faced the history of their families and their own story. Nazis, many of them with bloodstained hands, some condemned to death, some sentenced to years in prison, a sentence they often didn’t serve out, many who were never brought to justice, who went on working as physicians and judges, engineers and architects, living “distinguished” lives, these Nazis colluded in conspiratorial silence as weighty as a millstone under which life lies crushed beyond recognition and under which, by some inexplicable or, in fact, explicable miracle like Emperor Trojan’s goat’s ears, a grain of fragile truth would sprout here and there, truth that had a destructive, devastating power. It is incomprehensible that the children, the grandchildren, mostly asked no questions, that they still do not ask. But old photographs, unfinished manuscripts, hidden diaries surface; archives open, movies are made, books are written; the pebbles of history roll underfoot and in time our step grows less steady. Nazi, Fascist, Ustaša, Chetnik, regardless. Their germ has not been eradicated. Norman Frank understood this when he said, I will have no children, I want the vile Frank germ to disappear, then starts pouring milk down his throat, he drinks thirteen litres of milk per day, then dies. Norman’s brother Niklas, however, is alive. A defiant and tireless demystifier, Niklas Frank writes and shouts, and at his unambiguous, defiant declarations, articles, books and projects, not to say performances (such as when, for a couple of years in his childhood, he used to masturbate to the point of orgasm on the anniversary of Hans Frank’s execution), at every warning from him, the hypocritical and cowardly German public has been shocked for the last few decades, snarling at Niklas’ uncomprising stand, wanting to sleep easy, as if a father were a sacrosanct being. But he is not. There are no sacrosanct beings. Even God is not sacrosanct, perhaps He least of all.

Читать дальше