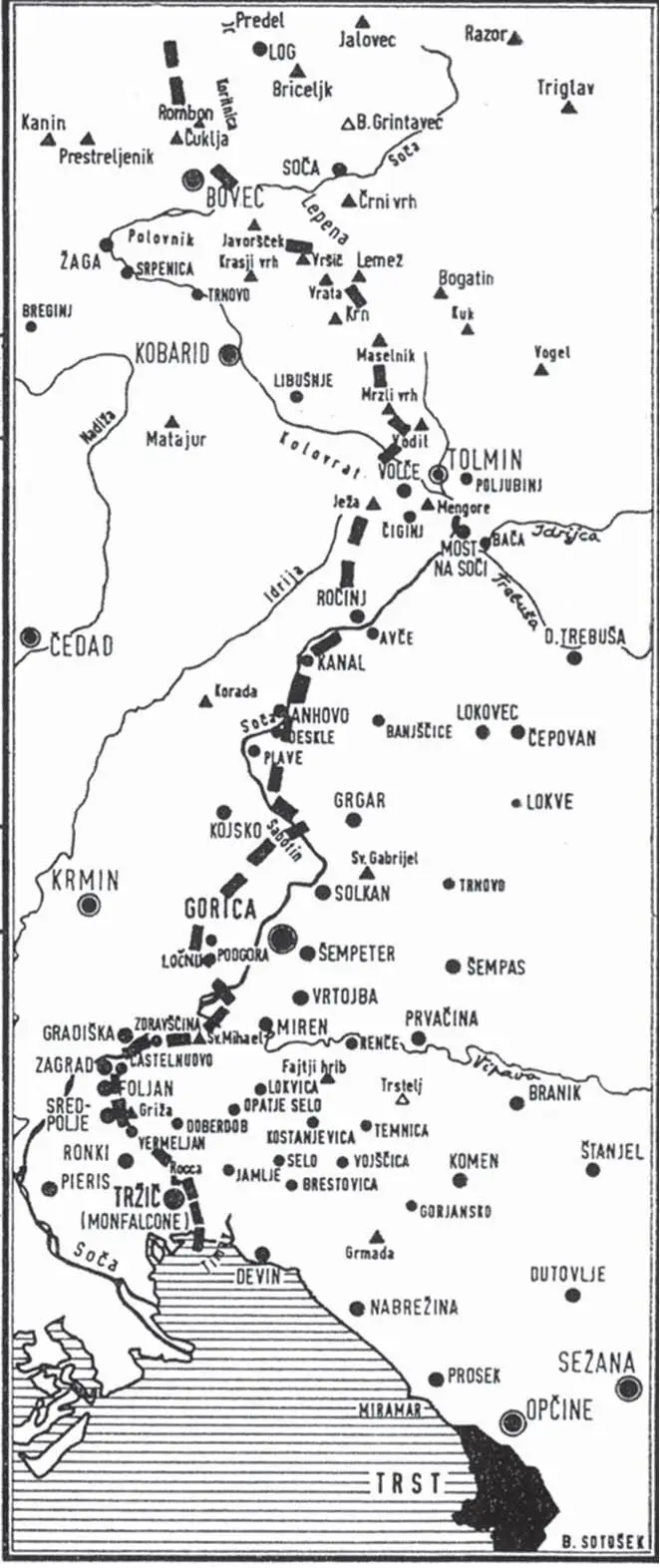

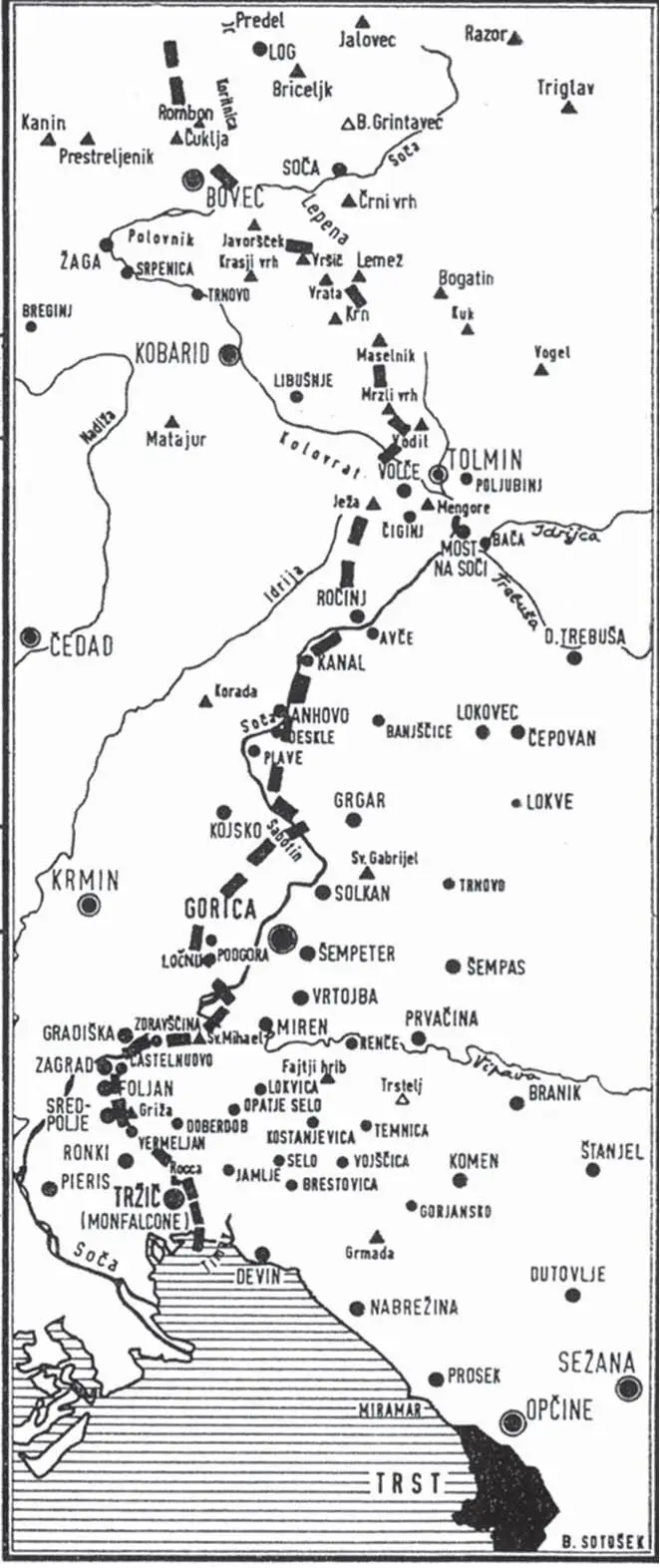

It is 25 May, 1915. The last passenger train crosses Solkan Bridge on its way from Vienna to Trieste. Solkan Bridge is battered, bombed, repaired and then hit again by a barrage of fire, and over it roll batteries, columns of soldiers of opposing armies march over it until 1918—the Austro-Germans and the Italians. Bruno Baar marches, too.

In the bloodiest of all eleven or twelve battles waged along the Soča, the Sixth, fought from 5 August to 17 August, 1916, Italy opens the way through to Trieste. In the embrace of its lavish gardens and palaces, shielded by mountain ranges, with the Vipava and the Soča as a diamond necklace on its bosom, Gorizia, a little Homburg, a treacherous copy of Baden-Baden, would for many years to come fail to draw the Austrian aristocracy as it had once drawn them during the hot summer months.

General Cadorna lines up twenty-two Italian divisions along the Soča on 5 August, 1916. On the other shore, nine divisions of weary and dispirited Austro-Hungarian troops await the order to attack, most of them too young and too old for warfare.

Bruno Baar is forty-nine. He has a pot belly, three children and a wife who bakes cakes for the Austrian soldiers. He has a winery in which he no longer makes wine. He has a collection of the latest seventy-eights, to which he is not able, just then, to listen, so he dreams of them as he marches along the flooding banks of the Soča, humming “La donna è mobile”, because he adores Caruso. Meanwhile, his Marisa, swaying on dented high heels, carries walnut crescents to the brothel for the Austro-Hungarian officers, and imagines that she is Bice Adami bringing the audience in Milan to their feet with her rendition of “ Voi lo sapete ”, accompanied by the piano. Marisa Baar, née Brasic, does her best to sing soprano, but without success, her voice is coarsened by harsh tobacco. A droplet of summer rain falls on her eyelash, where it lingers, making a miniature crystal ball which reflects her future. Marisa Baar sings “Voi lo sapete” without an inkling that Bice Adami will long outlive her.

Cadorna begins the battle with a diversionary artillery volley on 6 August, 1916. He places two infantry units to the south on the Monfalcone side with two corps each as decoys. Cadorna’s ruse does not work. The Austrian units do not budge. As it was, Count Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf had already cut back the number of troops along the Soĉa front in order to bolster his offensive near Trentino. Hence Cadorna swiftly deploys his troops from Trentino by train (on the Transalpina line) to the Soča. Fierce fighting, dangerously out of control, begins two days later in Oslavia and on Podgora Mountain, when Cadorna captures the peak of Mount Sabatino. Units of the 12 th Italian Division march into Gorizia on 8 August. The Italian Army crosses the Soča the next day under a barrage of fire. Holding their guns high over their heads as if they were carrying children, as if they were greeting the sky, the soldiers plunge into the river singing the Garibaldi hymn:

Si scopron le tombe, si levano i morti

i martiri nostri son tutti risorti!

Le spade nel pugno, gli allori alle chiome,

la fiamma ed il nome d’Italia nel cor:

corriamo, corriamo! Sù, giovani schiere,

sù al vento per tutte le nostre bandiere .

Sù tutti col ferro, sù tutti col foco,

sù tutti col nome d’Italia nel cor .

Va’ fu ori d’Italia,

va’ fu ori chè l’ora!

Va’ fuori d’Italia,

va’ fu ori o stranier!

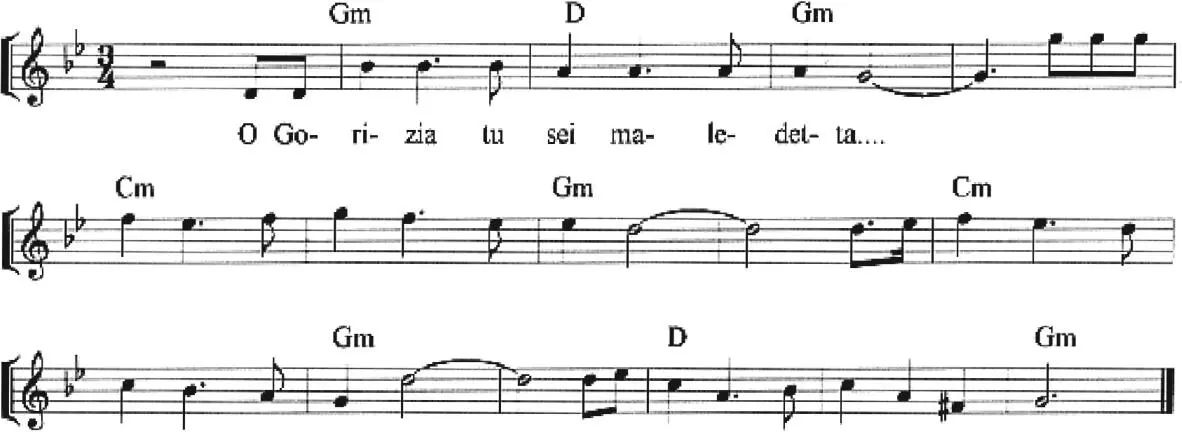

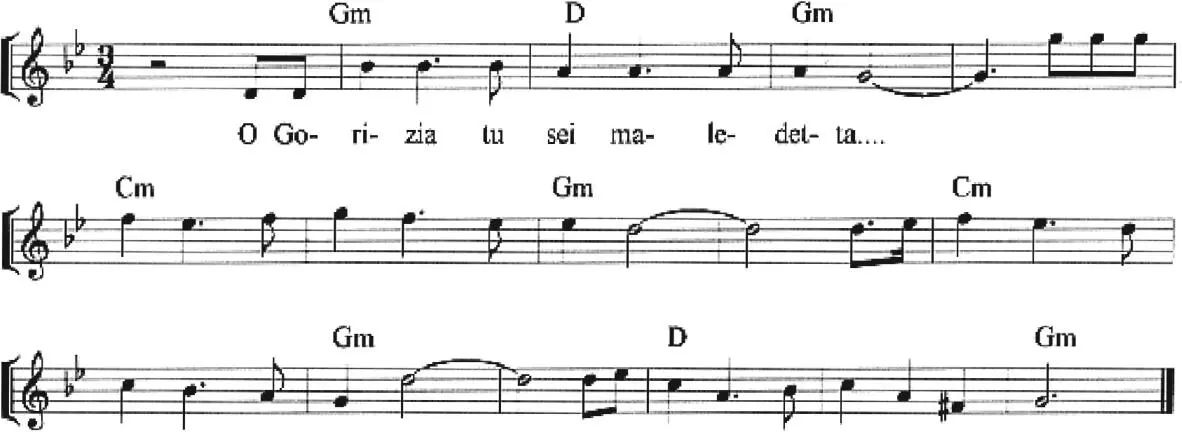

Later people will sing other songs. Mostly women will sing, and mostly they will sing a song with the refrain, “O, Gorizia, tu sei maledetta ”.

Austrian shrapnel whistles, churning the drunken Soča into a pool of green-blue foam. Then a terrible silence settles in, pierced by the sun’s sharp rays, and a vast crimson veil dances on the Soča, wet and sticky and thick. The army bugles sound the signal to charge and the grey uniforms line up in a protective firewall. This living wall, resembling insects with their wings plucked, howls Avanti Savoia! The stone bridge over the Soča has been hit the day before. Engineers ready the railway bridge over which the railway line runs from Milan and Udine to Gorizia and Trieste. The Italian fighting batteries, now in tatters and gashes, gallop over to the other side, firing at the Austrians, who fall back. Following the soldiers under a forest of spears are the Carabinieri, the Alpini, the Bersaglieri, the infantry and the cavalry. As far as one side is concerned, Gorizia is taken. For the others, Gorizia has fallen.

Bruno Baar scrambles up a hill and watches the battle, hidden behind the scratchy trunk of a hundred-year-old pine tree on which someone has carved a heart. They seem to him like idle children who have chosen to split into two camps separated by a slender thread. As if on both sides of the thread these children are lying flat on their stomachs, puffing, and the thread rises into the air, twists into a snake and falls like a waft to the ground. That thread is the border, Bruno Baar says. It will always twist and turn . Then he says, I’ll go and turn myself in .

Twenty thousand Italian soldiers are killed at the Sixth Battle of the Soča and 31,000 of them disappear or are captured. The Italians take 19,000 soldiers of the Austro-Hungarian Army prisoner. They capture sixty-seven pieces of artillery weaponry and a heap of mines and machine guns. The Austrian losses come to 71,000 men, some of whom are killed, some missing in action and some taken prisoner. The tally of casualties for all twelve battles along the Soča for the Italians is 1,205,000, and for the Austrians, 1,291,000.

The losses of the Kingdom of Italy on the Austro-Hungarian front in World War One are: 650,000 killed, 947,000 wounded, 600,000 taken prisoner or missing in action; 2,197,000 victims in total.

The losses for the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy on the Italian front are: 1,200,000 killed, 3,620,000 wounded and 2,200,000 taken prisoner or missing in action; a total of 7,200,000 people are casualties one way or another.

Later, a medal was designed to commemorate the taking of Gorizia. It was awarded to the bravest, both those who survived and those who were killed. The ones who went missing in action were unable to receive the medal. These men missing in action are a big problem, one cannot simply go missing. Turn into nothing. The missing are a problem because they turn up sooner or later. They come back. No matter when, no matter in what shape, they return, whether in someone else’s body, in someone’s voice, they always leave a trace. When they come back they are a nuisance, because the medals have already been doled out. The medal for valour at the Sixth Battle of the Soča is an important medal. It is a testament to the battle over the only corridor that led out of Italy into Austro-Hungary. The largest number of Italian medals was given to fighters of the 45th Infantry Division, because the most fighters were killed in the 45th Infantry Division. At the Soča. In the Soča. A local Gorizia resident, Castellucci, “designed” the medal. Today there are few such medals on the market. They are rare, so their value is rising. Collectors pay €50 and more for one. Precisely as much as a forgotten life is worth. Along with the medals, there are souvenirs and mementos of the battles along the Soča. Genuine souvenirs and those of more recent vintage. For instance, a twenty-centimetre-high, nickel-plated vase made from an eighty-millimetre shell, with etchings on it of towers and a gateway, describes the march into Gorizia. These vases are inscribed with the words Ricordo im Gorizia and Ricordo di Gorizia, and Bruno Baar keeps his in a display case as if they were trophies. Here:

Читать дальше