“Finnity’s complying.”

“Doesn’t have a choice, and neither do you.”

“Book of the century. Of the millennium. I get it — what’s next? An age is a million years? An epoch 10 million years? Or what’s beyond that — an era or eon?”

“Be serious — there are penalties if anyone blabs.”

“Penalties?”

“Inwired: if word gets out, the contract’s canceled.”

“Abort, abort.”

“Autodestructo.”

“So not a word.”

“Rach.”

“No Rach.”

“Shut your mouth.”

I shut my mouth.

The diner just had pencils — I picked my teeth with a pencil, until a pen was found.

A caper was stuck in my teeth.

://

I left Aaron in a stupor — Aar taxiing to his office to process, me to wander stumbling tripping over myself and, I guess, cram everything there was to cram about the internet? or web? One was how computers communicated (the net?), the other was what they communicated (the web?) — I was better off catching butterflies.

I wandered west until, inevitably, I was in front of the Metropolitan.

I used to spend so much time there, so many weekend and even weekday hours, that I’d imagine I’d become an exhibit, that I’d been there so long that I, the subject, had turned object, and that the other museumgoers who’d paid, they’d paid to see me, to watch how and where I walked, where I paused, stood, and sat, how long I paused at whatever I was standing or sitting in front of, when I went to the bathroom (groundfloor, past the temporary galleries of porcelain and crystal, all the tapestries reeking of bathroom), or for cafeteria wine and then out to the steps to smoke, whether I seemed attentive or inattentive, whether I seemed disturbed or calmed — as if I were carrying around this placard, as if I myself were just this placard, selfcataloging by materials, date, place of finding, provenance: carbonbased hominid, 2011, Manhattan (via Jersey) — a plaque and relic both, of paunchy dad jeans, logoless tshirt untucked, sportsjacket missing a button, athletic socks, unathletic sneaks.

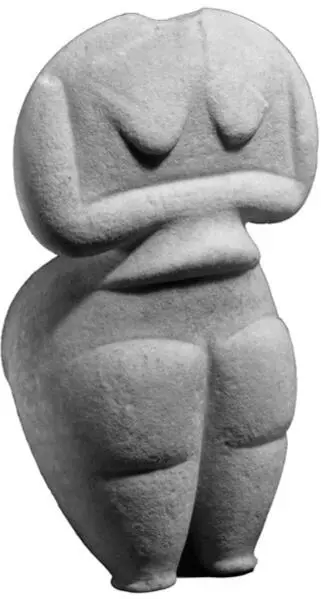

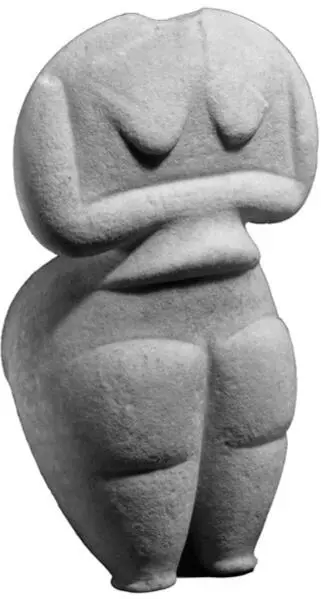

I visited the Met for the women, not for meeting them new, but for the reassurance of the old. For their forms that seduced by soothing — for their form, that vessel shape, joining them in sisterhood as bust is joined to bottom.

I visited to be mothered, essentially, and it was altogether more convenient for me to get that swaddling from the deceased strangers buried uptown than from my own mother down in Shoregirt.

The physique I’m feeling my way around here is that of the exemplary vase: a murky womb for water, tapering. I’m remembering a certain vase from home, from the house I was raised in: marl clay carved in a feather/scale motif, the gashes incised by brush or comb, then dipped transparently and fired, and set stout atop the cart in the hall. That was the pride of my mother’s apprenticeship: a crudely contoured holder for any flowers I’d bring, which she’d let wilt and crumble dry, as if measures of my absence. Yes, coming to the museum like this, confining myself behind its reinforced doors and metal detectors, and within its most ancient deepwide hushed insensible receptacles, will always be my safest shortcut to Jersey, and the displays of the Master of Shoregirt — Moms the potter — who’s put together like this, like all the women I’ve ever been with, except Rach.

\

Just to the left of the entrance of the Met, where civilization begins, where the Greek and Roman Wing begins — there it was: the dwellingplace of the jugs, the buxom jugs, just begging to surrender their shapes to a substance.

Curvant. Carinated. Bulging. The jar girls, containments themselves contained, immured squatting behind fake glass.

I used to stop, stoop at the vitrines, and pay my respects — breathing to fog their clarity, then wiping with a cuff.

I should say that my virgin encounter with these figures was in the company of Moms, who’d drive the family up 440 N across all of Staten Island for culture, for chemo (the former for me, the latter for Dad, whom we’d drop at Sloan Kettering).

But that Friday this past spring, I didn’t see any maternal proxies. Coming close to these figures, all I could see was myself. At each thermoplastic bubble, each lucite breach, I hovered near and preened. I was shocked, shattered, doubly. My chin quadrupled in reflection. My mouth was a squeezed citron. Stubble bristled at every suggestion. What had been highbrow was now balding.

Returning from that first chemo visit, Moms went and bought some clay, a wheel, some tools. Impractical platters, flaccid flasks: she’d been inspired to pot, moved to mold, vessels for her depression, while I had been, inadvertently, sexualized.

Moms had intended to inculcate only a fetish for art, not for what art must start as: body, the body defined by waist.

Dad, weakened, shriveled — a mummy’s mummy — had six months left to live.

\

That day, signing day, I took my tour, conducted my ordinary circuit by gallery: first the women, then the men. Rounding the rotundities, before proceeding to those other busts, those heads.

Staved heads — of the known and unknown, kings of anonymity with beards of shredded feta, or ziti with gray sauce — separated for display by the implements that might’ve decapitated them. If it’s venerable enough, weaponry can look like art, just like commonplace inscriptions can sound like poetry — Ozymandias, anyone? “this seal is the seal of King Proteus”?

The armor of a certain case has always reminded me of cocoons, chrysalides, shed snakeskin — all the breastplates and armguards and sheaths for the leg just rougher shells from an earlier stage of human development. The armor featured in an adjacent case, with its precisely positioned nipples and navels, sculpted pecs and abs, would’ve been even stranger without them. The men without bodies were still better off than the men just lacking penises, or testes. Regardless, statuary completed only by its incompletion, or destruction, resounded with me, while the swords hewed through my noons, severing neuroses.

But then I returned, I always returned, to my women, closing the show, a slow, agonizingly slow circumflexion.

Fertility goddesses, that’s what the archaeologists who’d dug them up had said, that’s what Moms had said, and I’d believed her — these women were the idols of women and women were the idols of men and yet we kept smashing them (I understood only later), smashing with rose bouquets, samplers of marzipan and marrons glacés, getaway tickets, massage vouchers, necklaces, bracelets, and words.

It strikes me that Moms herself might’ve believed that these odd lithic figurines were for fecundity, because everything else had failed her — the inability to conceive (and the inconceivability of) were fates she’d share with Rach, or else the problem was mine.

And Moms might even have been so distraught by Dad’s decline as to have placed genuine faith in the power of that petrified gallery — guiding me through rooms now changed, antiquity redecorated since 1984—because suddenly I wasn’t enough, she wanted another: a boy, though what she needed was a girl in her image.

If so, then that studio she had erected at home — her installation of a kiln in Dad’s neglected garage — must be regarded as a shrine, a temple to opportunity lost.

\

Читать дальше