In another dream Shaykh `Abd al-Kamil from Meknes, my companion in the time I spent in the zawiya on Jabal Musa in Sabta, appeared.

"Do you remember me?" he asked.

"How could I not remember you?" I replied. "Had it not been for the mention of your name, I would not have been able to stay in the Meknesi residence in Mecca for so long!"

"Leave this ephemeral world now," he said, "and come to the eternal existence. This is where you'll find the genuinely pleasant life, boons and comforts the like of which no eye has ever seen, no ear has ever heard, and no human heart has ever thought of in the lower world. Did I not tell you that I would enter heaven through its wide gate? So come along. Your own gate may be even wider and larger…"

There was still another vision, but I can only recall a few nasty fragments of it. The young boy, Hamada, is screaming and shouting for me, begging his Creator to help him. A group of sordid Mamluks are toying with him and committing serial acts of sodomy on him.

I was flat on my bed for several days, and my health went from bad to worse. Sometimes I was bleeding from both nose and mouth; it was almost as though the blood intended to drain away completely. When I realized that my medicaments were not having any effect on my worsening condition, I gave up and took a large dose of herbs that I knew from experience would be able to tranquilize me. I hid the rest of the potion in my belt alongside the dagger.

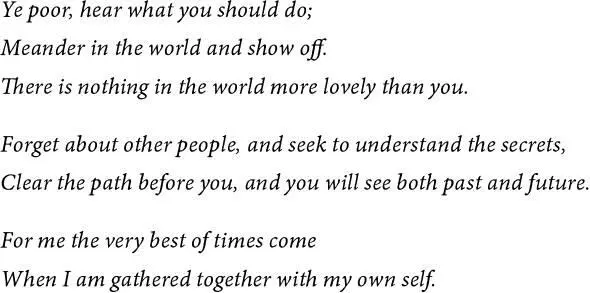

I now decided that my condition might improve somewhat if I took an exploratory stroll around some of the quarters of Mecca at dawn. So I washed and did my ablutions, perfumed myself, and donned my nicest clothes. I stole out to the stables, got on my horse, and let it wander wherever it wished. As it ambled slowly around the city, I realized that we had reached the southern slopes of Mount Abu Qubays,* so I took the opportunity to bid farewell to the house where the Prophet had been born. I then turned in the direction of the Bilal Mosque and prayed as much as I was able, all in preparation for a visit to Medina in spite of the known enmity of its governor and all its juridical authorities. But the path in front of me seemed to have been cut-taunting me with the name of my beloved student `Ali al-Nasir. The very idea seemed to me even more impossible than clearing a virgin forest or fertilizing a rocky mountain, not least because the midday sun was beating down and I was starting to bleed again from my nose and mouth. I decided to retrace my steps. As I was approaching the outskirts of Mecca, the pains in my head and body suddenly became worse than ever before, and I had no alternative but to swallow the rest of my herbal potion. My hope was to be able to endure the agony I was feeling. Staring at the sun high in the sky, I continued on my way, chanting as loudly as I could:

When I reached the places where people were gathered and crowding around, I got a cupper to shave my head completely, then exchanged my fine clothes so I could disguise myself in a jallaba and headcloth, and set my horse free to wander wherever God willed. That done, I made for the Ka`ba shrine and circumambulated the black stone several times till I started feeling giddy. I lay down for a while near a pillar and lost consciousness for a while. When I came round, I discovered that my mouth had a gold coin in it; some rich foreign pilgrim had obviously put it there as an act of charity as they usually do with poor, needy folk who are sleeping in the mosque. I took the gold coin and put it in another sleeping ascetic's mouth. I then headed for a fairly deserted wall in the outer courtyard and sat down in the sun with my back leaning against the wall. The pain now eased somewhat. Using whatever level of consciousness remained, I started to review my life in the context of its imminent erasure amid the whirlwinds of oblivion.

In my estimation some small portion of my life would linger; maybe nothing more than that. In any case, here is what I would say to anyone who does remember me and writes about me:

Whatever else you forget, do not forget that, to the extent that I could, I encapsulated myself in the processes of growth and ascent to loftier planes. If I did manage to transcend my lower existence, then, by God who is the Truth, my only motivation was a sensible and individual desire, one with no equal: to speed my journey toward the Necessary Existent and to find perfection in the glow of divine abundance.

Through my cloudy vision Baybars now appeared, looking like a savage ghoul with a vicious, angry countenance.

"You heretic," he was yelling, "don't think you're going to escape my punishment. When you did those circumambulations a while ago, you looked just like donkeys around a mill-wheel!"

"Most people are like that, if you only knew," I replied, facing him down. "They claim to be carriers of the Qur'an, but in fact they have no awareness of it nor do they understand it. The simile used in the text of the Qur'an is exactly applicable to them: `The example of those who were given the Torah but then did not carry it is like the donkey carrying texts."'

With that, the Mamluk sultan issued his orders: "Grab this unbeliever. Grab him and kill him!"

Time went by, although I have no idea how long. Gradually the shapes of people and objects turned into blurry images of a kind I had never experienced before. I closed my eyes so that I could protect myself and think about something else. Before long I watched as two octopus-like arms, long and powerful, stretched downward toward me and started lashing me with heavy blows. When they had finished, they were replaced by scorpions, vipers, and hornets, which started stinging me all over. They were followed by scavenger birds that kept pecking and gnawing at me.

Just a rainbow's distance from death, I was bleeding all over when Baybars reappeared, this time at the head of an army that was marching toward me.

"So, you renegade," he yelled, "you disobey me and write that anyone who does obeisance to Turks is only motivated by grief and idolatry. Take him away and kill him…"

I had neither breath nor energy to respond. I took out my dagger to defend myself. With that the soldiers surrounded me and started pounding and throttling me. Their leader grabbed my right hand, which was holding the dagger, and slit the veins. As I breathed my last, I kept repeating:

Appendix. What Some Writers Have Said about Ibn Sab'in

— Al-Shushtari, in praise of Ibn Sabin, Diwan [Collected Poetry]

Ibn Sabin was more knowledgeable about philosophy than Ibn al In theology, both of them sought information from the same source, namely alJuwayni, the author of the Irshad, and his followers such as Al-Razi. Ibn Sabin was a major heterodox figure, a polytheist and magician. He was by far the brightest and cleverest of them all, and the most knowledgeable in matters of philosophy and philosophical Sufism.

— Ibn Taymiyya, Al-Rasa'il wa-al-Masa'il [Epistles and Questions]

Ibn Sabin studied the ancients and philosophy. As a result, he was to a certain extent heterodox in his views and composed in that vein. He was expert in the interpretation of symbols and made full use of this skill to hoodwink stupid rulers and wealthy people.

— Ibn Kathir, Al-Bidaya wa-al-Nihaya [The Beginning and End]

Читать дальше