My best friend, Dina, showed up, crossing from East Beirut. When she stood in front of me, I broke down. “May you be compensated with your health,” she said formally, tears flowing down her face. She hesitated, slowing the line of people. “I’m so sorry,” she added. She moved on to my sisters and stepmother on my right.

When she sat in the far corner of the hall, I left my seat and joined her. We held hands silently and watched as relatives and friends streamed in.

“I’m leaving,” she said suddenly. “I’m going to Boston. I can’t take this anymore. I don’t think I’m ever coming back here.”

“When are you guys leaving?”

“It’s just me,” she said. “They don’t want to leave Lebanon yet. They think things will improve.”

“They’re going to let you leave by yourself?”

She looked at me sideways, scrunching her face. “After all this,” she said, “you think they consider it better for me to stay in Lebanon?”

A couple of Druze men came in wearing army fatigues. Even though they were unarmed, the air tensed. They offered their condolences to the women and left for the men’s hall.

“Are you doing all right?” Dina asked. Her face was lightly made-up, traces of wiped red lipstick clung to the left corner of her mouth.

“Not very well,” I replied. “I just can’t believe she’s gone. I still think I’ll wake up. How does one deal with something like this? You know, my family is very close in many ways but we do not talk about things. My father locks himself in a room. My stepmother shuts down. We try to pretend a crisis never happened. If we don’t talk about it, it will disappear.”

A short, dumpy woman walked in, wearing an old scarf and a tattered overcoat even though it was summer. Her face looked familiar, but I did not recognize her. She offered her condolences to the family, shook each hand quickly and moved to the next. She then sat alone on the side. My aunt began whispering to my stepmother. My relatives were abuzz.

Nervous chitchat moved around the room like a wave, up and down, side to side. Behind us, a voice said, “I can’t believe the gall. Has she no shame? Someone should kick her out.”

Dina looked at me uncomprehending. I scrutinized the woman and finally realized why her homely face was familiar. “It’s his mother,” I said.

Dina’s face dropped. “Oh, my God. What is she doing here?”

“I don’t know. She must have traveled all night.”

The chair she sat in looked like it was a couple of sizes too big for her. She sat avoiding gazes, looking at the floor. The closest women to her were from our father’s village and they stood up and left the room hurriedly, without shaking hands with anyone. The soldier’s mother kept still, her head down, her hands on her lap, fingers entwined. Only her left thumb twitched sporadically. My aunt stood up, her eyes filled with menace. The chair she was sitting on fell backward, an ear-splitting sound. She began moving toward the soldier’s mother, but my stepmother stopped her. My stepmother strode over to the murderer’s mother, sat down next to her. They did not exchange words. The room hushed completely. My stepmother reached over, covered the woman’s hand with hers. The soldier’s mother cried silently.

For Dina

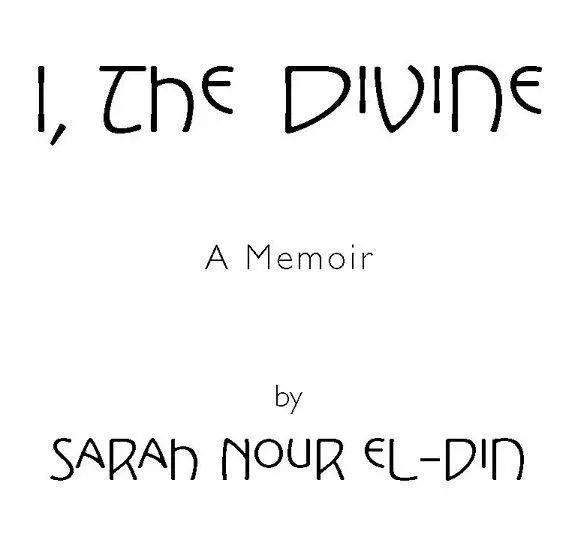

My grandfather, Hammoud, named me for the great Sarah Bernhardt. He was infatuated with her. Since he chose my name, stamped me, I immediately became his favorite granddaughter.

As a child, I spent as much time at my grandfather’s house as I did at ours. My grandparents lived in a spacious apartment only two buildings away. Even though my father was educated, a physician, he viewed education only as a means of achieving a better professional position rather than as a process of satisfying intellectual curiosities. My grandfather, on the other hand, was a newspaperman. His mind was filled with information and trivia, which he shared with anyone who would listen, and I loved to listen.

I spent most of the time with my grandfather in the family room, a green-walled, well-lit room filled with books. I sat on his lap as he regaled me with stories. He told all kinds of tales, but his favorites were about the Divine Sarah, the goddess of the stage. These I came to know by heart.

“Her real name was Henriette-Rosine Bernard,” he told me, “but she’ll always be Sarah Bernhardt, the Divine Sarah, the greatest woman who ever lived. She broke every man’s heart. When she was up on stage, the earth moved, the planets collided, and the audience fell in love. I was a little boy when I met her, not much older than you, but I knew I was in the presence of the greatest actress in the world.”

“Her hair,” went another story, “her hair was red like fire, bright red, and her voice, oh my, her voice was the most beautiful in the world. When she spoke it was like singing. I was a young boy when I met her, and she an old woman, but I would have married her, if I could. I would have married her right there. But everybody wanted to marry her. Her red hair was almost like yours was when you were a baby. If we colored your hair now, you would look just like her. And she was a firecracker, just like you.”

I grew up believing I was the Divine Sarah. I could do anything I wanted. This gift from my grandfather was the greatest bestowed on me. Growing up female in Lebanon was not easy. No matter how much encouragement parents gave their daughters, pressures, subtle and not so subtle, led girls to hope for nothing more than a good marriage. Being the Divine Sarah, I was oblivious to such pressures, much to the consternation of many. As a child, I was a tomboy, unaware of how girls were supposed to behave. I became a good soccer player. I excelled at mathematics in school. I wore dungarees and tennis shoes.

His stories had little effect on anyone else. My sisters, Amal and Lamia, were unimpressed. My stepmother objected to my hearing stories of wayward women, but my grandfather persuaded her it was a harmless activity. Years later, she would blame my becoming a tramp, as she once called me, on those stories, which by the age of five I was able to repeat word for word. I wanted to be an actress. I would stand in front of the mirror in my room thanking my audience. I delivered incomprehensible monologues as Racine’s Phèdre without having any idea what the play was. Lamia, who was two years older, got so fed up with the performances, she slapped me across the face. I cried, ran to my father, complained about her, and when she came after me to defend herself, I stood behind my father, orating a new monologue just to annoy her. To this day, with all her problems, what with being institutionalized and all, she is my least favorite sister.

As I grew older, I began to ask more questions of my grandfather. How did he come to meet the Divine Sarah? He was with his father, a highly ranked, poorly paid diplomat of the decaying Ottoman Empire who was visiting Paris on a diplomatic mission. They saw a play and my grandfather was taken backstage to meet her. How old was he? Eleven, the year was 1912. The play? Edmond Rostand’s L’Aiglon. The hero of this play was Napoleon’s son, who was kept in semi-captivity after the fall of the empire. The Divine Sarah was a middle-aged woman playing a boy’s part. I was enthralled. Was she great as Napoleon’s son? She was incredible. She ran across the stage, jumping from place to place, delivering her lines with such intensity, such integrity, the audience forgot they were watching the Divine Sarah. They were watching Napoleon’s son walking the stage.

Читать дальше