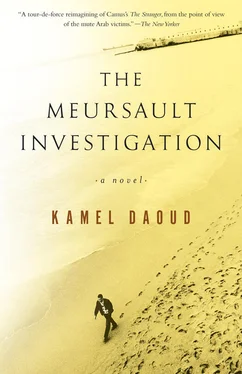

Kamel Daoud - The Meursault Investigation

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kamel Daoud - The Meursault Investigation» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Other Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Meursault Investigation

- Автор:

- Издательство:Other Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Meursault Investigation: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Meursault Investigation»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

In a bar in Oran, night after night, he ruminates on his solitude, on his broken heart, on his anger with men desperate for a god, and on his disarray when faced with a country that has so disappointed him. A stranger among his own people, he wants to be granted, finally, the right to die.

The Stranger

The Meursault Investigation

The Meursault Investigation — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Meursault Investigation», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

What would you call a story that puts four characters around a table: a Kabyle waiter the size of a giant, an apparently tubercular deaf-mute, a young graduate student with a skeptical eye, and an old wine bibber who makes assertions but offers no proofs?

XV

I beg you to forgive this old man I’ve become. Which is itself a great mystery, by the way. These days, I’m so old that I often tell myself, on nights when multitudes of stars are sparkling in the sky, there must necessarily be something to be discovered from living so long. Living, what an effort! At the end, there must necessarily be, there has to be, some sort of essential revelation. It shocks me, this disproportion between my insignificance and the vastness of the cosmos. I often think there must be something all the same, something in the middle between my triviality and the universe!

But often enough I backslide, I start roaming the beach with a pistol in my fist, scouting around for the first Arab who looks like me so I can kill him. With my history, tell me, what else can I do but replay it over and over? Mama’s still alive, but she’s mute. We haven’t spoken for years, and I content myself with drinking her coffee. The rest of the country is of no concern to me, except for the lemon tree, the beach, the bungalow, the sun, and the echo of the gunshot. And so I’ve lived this way a long time, like a sort of sleepwalker, shuttling between the offices where I’ve worked and my different residences. Some sketchy affairs with various women, a lot of exhaustion. No, nothing happened after Meriem left. I lived like the other people in the country, but with more discretion and more indifference. I watched the post-Independence enthusiasm consume itself and the illusions collapse, and then I started to get old, and now I’m sitting here in a bar, telling you this story that nobody ever tried to hear, except for Meriem and you, with a deaf-mute for a witness.

I’ve lived like a sort of ghost, observing the living as they bustle about in this big fishbowl. I’ve known the giddy feeling that comes with possessing an overwhelming secret, and that’s how I’ve walked around, with a kind of endless monologue in my head. There have certainly been moments when I had a terrible urge to shout out to the world that I was Musa’s brother and that we, Mama and I, were the only genuine heroes of that famous story, but who would have believed us? Who? What evidence could we offer? Two initials and a novel where no given name appears? The worst was when the packs of moon dogs started fighting and ripping one another apart to establish whether your hero had the same nationality as me or the people who shared his building. A fine joke! In the scuffle, nobody wondered what Musa’s nationality was. He’s referred to as the Arab, even by Arabs. Tell me, is that a nationality, “Arab”? And where’s this country everybody claims to carry in their hearts, in their vitals, but which doesn’t exist anywhere?

I went to Algiers a few times. Nobody talks about us, about my brother or Mama or me. Nobody! Our grotesque capital city, exposing its entrails to the open air, seemed like the worst of all the insults hurled at that unpunished crime. Millions of Meursaults, piled on top of one another, confined between a dirty beach and a mountain, dazed by murder and sleep, colliding with one another for lack of space. God, how I loathe the city of Algiers, the monstrous chewing sound it makes, its stench of rotten vegetables and rancid oil! It doesn’t have a bay, it has jaws. And its waters won’t be returning my brother’s body to me, that’s for sure! Once you’ve seen that city from the back, you can understand why the crime was perfect. And so I see them everywhere, your Meursaults, even in my apartment building here in Oran. Facing my balcony, just behind the last building on the outskirts of the city, there’s an imposing mosque standing unfinished, like thousands of others in this country. I often look out at it from my window, and I loathe its architecture, the big finger pointed at the sky, the concrete still gaping. I also loathe the imam, who looks at his flock as if he’s the steward of some kingdom. The hideous minaret makes me itch to speak some absolute blasphemy, something along the lines of “I will not prostrate myself before your pile of clay,” and to repeat it in the wake of Iblis, the devil himself … Sometimes I’m tempted to climb up that prayer tower, reach the level where the loudspeakers are hung, lock myself in, and belt out my widest assortment of invective and sacrilege. I long to list my impieties in detail. To bellow that I don’t pray, I don’t do my ablutions, I don’t fast, I will never go on any pilgrimage, and I drink wine — and what’s more, the air that makes it better. To cry out that I’m free, and that God is a question, not an answer, and that I want to meet him alone, at my death as at my birth.

After your hero was sentenced to die, a priest visited him in his cell; in my case, there’s a whole pack of religious fanatics hounding me, trying to convince me that the stones of this country don’t only sweat with suffering, and that God is watching over us. I should shout out to them, say I’ve been looking at those unfinished walls for years, there isn’t anything or anyone in the world I know better. Maybe at one time, way back, I was able to catch a glimpse of the divine order. The face I saw was as bright as the sun and the flame of desire — and it belonged to Meriem. I tried to find it again. In vain. Now it’s all over. Can you imagine the scene? Me bawling into the microphone while they scramble to break down the door of the minaret so they can stop my mouth. They try to make me listen to reason, they’re distraught, they tell me there’s another life after death. And I answer them and say, “A life where I can remember this one!” And then I die, maybe stoned to death, but with the mic in my hand, me, Harun, brother of Musa, son of the vanished father. Ah, the martyr’s grand gesture! Crying out his naked truth. You live elsewhere, you can’t imagine what an old man has to put up with when he doesn’t believe in God, doesn’t go to the mosque, has neither wife nor children, and parades his freedom around like a provocation.

One day the imam tried to talk to me about God, telling me I was old and should at least pray like the others, but I went up to him and made an attempt to explain that I had so little time left, I didn’t want to waste it on God. He tried to change the subject by asking me why I was calling him “Monsieur” and not “El-Sheikh.” That got me mad, and I told him he wasn’t my guide, he wasn’t even on my side. “Yes, my son,” he said, putting his hand on my shoulder, “I am on your side. But you have no way of knowing it, because your heart is blind. I shall pray for you.” Then, I don’t know why, but something inside me snapped. I started yelling at the top of my lungs, and I insulted him and said I wouldn’t put up with being prayed for by him. I grabbed him by the collar of his gandoura. I poured out on him everything that was in my heart, joy and anger together. He seemed so sure of himself, didn’t he? And yet none of his certainties was worth one hair on the head of the woman I loved. He wasn’t even sure he was alive, because he was living like a dead man. I might look as if I was the one who’d come up empty-handed, but I was sure about me, about everything, sure of my life and sure of the death I had waiting for me. Yes, that was all I had. But at least I had as much of a hold on it as it had on me. I had been right, I was still right, I would always be right. It was as if I had always been waiting for this moment and for the first light of this dawn to be vindicated. Nothing, nothing mattered, and I knew why. So did he. Throughout the whole absurd life I’d lived, a dark wind had been rising toward me from somewhere deep in my future. What did other people’s deaths or a mother’s love matter to me; what did his God or the lives people choose or the fate they think they elect matter to me when we’re all elected by the same fate, me and billions of privileged people like him who also called themselves my brothers? Couldn’t he see, couldn’t he see that? Everybody was privileged. There were only privileged people. The others would all be condemned one day. And he’ll be condemned too, if the world’s still alive. What would it matter if he were accused of murder and then executed because he didn’t cry at his mother’s funeral, or if I were accused of having killed a man on July 5, 1962, and not one day sooner? Salamano’s dog was worth just as much as his wife. The little robot woman was just as guilty as the Parisian woman Masson married, or as Marie, who had wanted me to marry her. What did it matter that Meriem now offered her lips to another man? Couldn’t he, couldn’t this condemned man see that from somewhere deep in my future … All the shouting had me gasping for air. But they were already tearing the imam from my grip and a thousand arms wrapped themselves around me and brought me under control. The imam calmed them, though, and looked at me for a moment without saying anything. His eyes were full of tears. Then he turned and disappeared.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Meursault Investigation»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Meursault Investigation» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Meursault Investigation» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.